How the Myth of the Population Bomb Was Born

As the world passes 8 billion people, a look back at the modern origins of neo-Malthusianism

As the world’s population officially passes 8 billion — today according to the United Nations — this post shares an excerpt from a 2019 paper of mine (with Björn-Ola Linnér) which explores the social construction of a myth of averted famine associated with the Green Revolution. The story of a looming global catastrophe only avoided by scientific and technological advances in agricultural production is conventional wisdom. But it is also wrong, as I explain in this post. The myth of averted famine and global catastrophe is a wonderful example of Rayner’s “social construction of ignorance” — a subject that is the focus of my lecture at the Oxford Martin School tomorrow.

Note: At the bottom of this post my paid subscribers have access to our full paper as a PDF. -RP

The Rise of Post-War Neo-Malthusianism

In 1798, Thomas Malthus published his famous essay on the possible catastrophic consequences of unchecked population growth. But it was not until the 20th century that the Malthusian specter of a population crisis occupied the attention of the scientific community and eventually became adapted to Cold War policy led by the United States (Linnér 2003).

The new prominence of neo-Malthusians in postwar policy was coincident with the greater authority of scientists in general. In 1949, the United Nations held a scientific conference on the “conservation and utilization of natural resources” which marked the emergence of resource concerns at the highest level of international politics. The relationship of science and politics during this period was rapidly evolving, with scientists looking for greater influence and funding, and the US government warily supportive, based on the contributions of science to helping win World War II (Zachary 2018). Politicians saw in resource concerns an opportunity for political expediency in the looming Cold War, while scientists were looking at an opportunity for greater influence.

The early efforts of agricultural technology improvements funded by the Rockefeller Foundation were initially not primarily motivated by concerns about population growth. But in the late 1940s, directly motivated by neo-Malthusian arguments, the Foundation’s agricultural programs were more closely linked to the concern of diminishing food resources in an overpopulated world and the perceived danger of political instability in areas where the population reached the limits of food subsistence (Perkins 1997).

The world experienced unprecedented population growth after World War II. Death rates were rapidly declining as health measures were becoming more accessible in poorer countries, sanitation was enhanced and large parts of the world improved their diets. Yet, birth rates associated with growing affluence had not yet begun to fall (Connelly 2008). The crude death rate fell markedly all over the world in the early 1950s, particularly in the least developed countries and less developed regions. The birth rate started to drop in the 1950s, but much slower. This temporal divergence between rates of change in death and birth rates is important for understanding the widespread Malthusian concern of the era.

Several developments, in particular, raised the global food production in the early postwar years: Technological changes had modernized agriculture, new seed varieties and vast areas of new land had been opened up for tillage and grazing outside Europe. The neo-Malthusians pointed at the marginalized land being rapidly exploited. The rapid increase in population, rising affluence and expansion of globalized trade heightened agricultural production. New lands were cleared. Highland regions were ploughed, rainforests were cut down, and dry land was to be made fruitful. The demand in the richer markets for coffee, citrus fruits, bananas and beef cattle required more fertile tropical lowlands. The subsistence food production had to move onto more fragile marginal land prone to soil erosion. An increased capacity for ploughing resulted from the rapid spreading of tractors and new heavy machinery after the Second World War. Although crucial for the agricultural productivity gain, heavy machinery also compacted soils. New irrigation practices brought new problems of soil salinity. Urbanization and roads took their share of fertile land. Land at the equivalent of the United Kingdom was paved over between 1945 and 1975 (McNeill 2000).

Rapidly rising population and the increased exploitation of marginal lands stirred images of an overpopulated planet plagued by a desperate exploitation of diminishing resources. The growing concern in the early postwar years was captured in concepts such as “the fifth plate,” referring to the 20% increase in population that was expected to take its place at the world’s dinner table by 1960 (Linnér 2003). Into the 1970s, warnings echoed of an impending danger that world famine would spread also to prosperous nations. Newspaper headlines spelled out anxiety about famines spreading across the world, even to the prosperous nations in Europe and North America. The concern expressed was that when the world’s hungry would demand their fair slice of the global pie, the rich industrialized countries would no longer be able to import from poorer, increasingly populous countries either basic food supplies, fodder, indispensable fertilizers or other goods produced from resources in those countries (Linnér 2003).

Immigration and population control were also a concern. Paul Ehrlich and John Holdren, two well-known neo-Malthusians expressed this concern in 1972 in terms of a clear metaphor:

If a leaking ship were tied to a dock and the passengers were still swarming up the gangplank, a competent captain would keep any more from boarding while he manned the pumps and attempted to repair the leak.

For neo-Malthusians the Green Revolution was only a temporary fix. In traditional Malthusian logic, new resources could in the long-run never keep pace with population growth. Neo-Malthusian concerns were voiced in the parliaments, government offices, the United Nations headquarters, and in boardrooms, radio shows, and lecture halls and on the front pages of newspapers and magazines. The message reverberated the population theory of Thomas Malthus that in the long-run population, if unchecked, inevitably grows faster than the supply of food.

The postwar Neo-Malthusianism took several inter-related forms: Among them a popular focus on population control to counter the social miseries of people growing in numbers and poverty, and an environmental focus on the impact of high population densities on scarce resources (cf. Connelly 2008; Linnér 2003). We briefly discuss each and its role in helping to set the stage for the emergence of the political mythology of the Green Revolution focused on averted famine.

Popular Neo-Malthusianism and Population Growth

In 1953, the Population Council was created and headed by John D. Rockefeller III to predict population growth and survey global resources. The New York Times applauded the creation of the organization as “economists, public health officials and governments” now reverberated the Malthusian “predictions of misery” (New York Times 1952).

In the last ten years we have witnessed a revival of the Malthusian doctrine that the world’s population is increasing more rapidly than its supply of food, minerals and other commodities considered necessary for the maintenance of a high standard of living.

The neo-Malthusian surge was also reflected in popular culture with an increase in popular characterizations of an ecological doomsday resulting from waste, pollution, or technology (Wagar 1982).

Several years earlier, the publisher of The Saturday Review of Literature captured the extinction angst in his 1948 article “What Shall We Do to Be Saved?”:

Three years after the Second World War the course of political and economic events has persuaded vast numbers of people that the doom of mankind is sealed… To the warnings of the fatal result of an atomic and biological war there are added the death knells rung by prophets of man’s starvation, resulting from the increase in the population of the globe from man’s continuing destruction of nature’s resources (Smith 1948: 20).

A reporter from The New York Times described the atmosphere: “Scientists…envisioned a dark outlook for the human race in the next century. They linked this outlook to over-population and the dwindling of natural resources both of which are the direct consequences of progress in science and technology” (New York Times1948).

At the beginning of the 1960s, ‘That Population Explosion’ was on the cover of Time magazine: “Long a hot topic among pundits … the startling 20th century surge in humanity’s rate of reproduction may be as fateful to history as the H-bomb and the Sputnik, but it gets less public attention.” The cover story gave numerous accounts from all over the world of an overcrowded planet, where people were living on an increasingly poorer diet, “their fury may well shake the earth.” The magazine pointed at the promise of technological and scientific innovations to remedy the problem. The 1960s also marked a turnaround in global food trading patterns. Up until World War II, many “Third World” regions were net exporters of food. By the 1960s, they had become net importers. By 1970, their imports of food had reached 20 million tons per year (Poleman 1975). The US Department of Agriculture was pessimistic in its prognosis at the beginning of the 1960s. The World Food Budget, 1963 and 1966, published in 1961, added to the sense of a population–resource crisis getting out of hand. The report concluded that in the so-called developing countries 1.9 billion people were inadequately nourished: “In most of them, population is expanding rapidly, malnutrition is widespread and persistent, and there is no likelihood that the food problem soon will be solved” (USDA 1961).

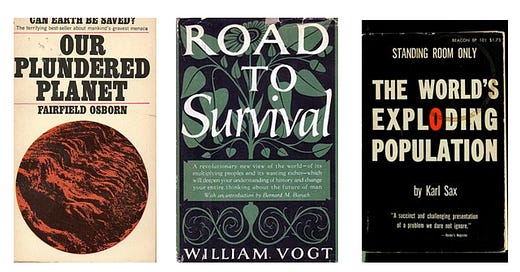

The relative lack of public attention to issues of population growth was soon to change. A voluminous outpouring of literature appeared on the population–resource dilemma in the early 1960s. Vogt published People: Challenge to Survival (1961) Fertility and Survival (1961), Our Crowded Planet (1962). In Essays of a Humanist (1964), Julian Huxley gives an illustrative description of the population concern of his time:

The neo-Malthusians, supported by the progressive opinion in the Western World and by leading figures in most Asian countries, produce volumes of alarming statistics about the world population explosion and the urgent need for birth-control, while the anti-Malthusians, supported by the tow ideological blocs of Catholicism and Communism, produce equal volumes of hopeful statistics, or perhaps one should say of wishful estimates, purporting to show how the problem can be solved by science, by the exploitation of the Amazon or the Arctic, by better distribution, or even by shipping our surplus population to other planets (Huxley 1964).

In a famous interview in Le Monde, philosopher Jean-Paul Sartre declared after a world tour that the confrontation with famine had changed him profoundly. After having seen children die of hunger, he concluded that human alienation on Earth, exploitations of humans, and malnutrition had to put all metaphysical evil into the background: “Hunger is the only thing, period” (as quoted in Linnér 2003). The late 1960s and early 1970s saw an upsurge in food experts, demographers and environmentalists, predicting that the coming three decades would see massive starvation and famine in parts of Africa, Asia, and Central and South America.

Hasell and Roser (2017) have compiled available data on famines from 1860 on, shown in Figure 2 [above]. Notwithstanding that malnutrition was a severe problem around the developing world, these data do not support the notion that the 1960s were a period of particularly extreme famine impacts (with the notable exception of China during it’s “Great Leap Forward,” which further illustrates the role that politics has played in major famine), at least as compared to earlier decades (see graph, Hasell and Roser 2017). Even so, the notion of global over-population had taken hold.

Environmental Neo-Malthusianism

Environmental Neo-Malthusianism held that the exponential growth in the number of people consuming and polluting already scarce resources would inevitably result in famine spreading around the world, ultimately even to a global ecological collapse or a third world war (Friedrichs 2014). Like Malthus, they predicted unplanned population checks. Environmental degradation caused by industrialization would also severely limit population growth. It was simply not possible for the Earth to support additional billions of people living at Western material standards, according to neo-Malthusians.

The second half of the 1960s saw accelerated outpouring of Malthusian thought with titles such as The Hungry Planet (1965), The Silent Explosion (1965), Famine –1975 (1967), Born to Hunger (1968). Paul Ehrlich’s 1968 bestseller, The Population Bomb, became one of the most widely read publications by an environmentalist. He argued that the economy expanded at a geometric ratio it would eventually run up against the limits of the earth: “A cancer is an uncontrolled multiplication of cells; the population explosion is an uncontrolled multiplication of people.” Ehrlich explained that the “gunpowder of the population explosion” was the ominous fact that people under 15 years of age made up roughly 40% of the population in what Ehrlich called the “undeveloped” areas. Ehrlich argued that when they come into reproductive age we would see the greatest baby boom of all time (Ehrlich 1968).

Environmental Neo-Malthusianism came in several modes. Lifeboat ethics was launched by Garret Hardin as a triage concept. It was too late to save all humankind, he argued, so it was better to save a select few than let all perish. Others emphasized the need to overcome unequal ecological and economic exchange and called for nutritional redistribution as a key measure to counteract the perils of population growth and diminishing resources (Linnér 2003).

The same year Ehrlich rose to fame, Hardin argued in “Tragedy of the Commons” that it was too late to stop population growth on a voluntary basis. Zero growth of birth rate had to be accomplished through compulsory legislation (Hardin 1968). The Club of Rome’s 1972 report Limits to Growth warned that the physical limits of the planet would be reached within a hundred years because of environmental degradation and pollution caused by population growth, food production, and industrialization. John Holdren, who later became science advisor to President Barack Obama, testified before Congress in 1974 that society was “a house of cards about to collapse” and called for a “conscious accommodation to the perceived limits of growth via population limitation and redistribution of wealth” (Holdren 1974).

The political myth of the Green Revolution as an averted famine was supported by environmentalists who had already adopted a stance on resource shortages and population growth consistent with the narrative of a global food crisis. The interests of Neo-Malthusians thus converged with the interests of those politicians who had advanced the idea of a looming global famine, and scientists who focused on population control and desired a greater access to government decision-making. One key difference between these groups is that many scientists and politicians saw the Green Revolution as a solution to the perceived crisis, whereas Neo-Malthusians saw it as exacerbating the problem of over-population which had created the crisis in the first place, in addition to creating new ecological and social problems, and thus only putting off Armageddon.

Perhaps somewhat ironically in political terms, the environmentalist focus on resource shortage overlapped with the interests of Cold Warriors looking to use resources as a weapon in their arsenal in the all-consuming battle against the spread of communism. Providing for a decent standard of living for the poor countries was regarded as one of the most effective means to hold communism at bay (Leffler 1992; Woods and Jones 1991; McCoullough 1992). In 1951, the Rockefeller Foundation published a report, “The World Food Problem, Agriculture, and the Rockefeller Foundation,” which linked the concerns about overpopulation to geopolitics. Overpopulation and inadequate or unequally divided resources were the root cause of global political tensions. Agriculture thus had an important political role to play in the superpower struggle. In 1949, Mao Zedong’s communist forces had prevailed in the Chinese civil war. The second most populous nation, India, was seen by US policymakers as at risk of a communist takeover.

In short, politicians, scientists and environmentalists converged on the political myth of a global population explosion, looming resource shortages and, ultimately, a narrative of famine averted.

Almost 50 years after Borlaug’s Nobel Prize, it may be impossible to reshape the political mythology of the Green Revolution as the world calls for its successor. The constant reappearance of the Malthusian population principle was described as follows in 1977 by economist Herman E. Daly: “Malthus has been buried many times, and Malthusian scarcity with him. But as Garret Hardin remarked, anyone who has been buried so often cannot be entirely dead” (Daly 1991).

Please consider sharing. Comments are always welcomed. And if you are new here, please consider a subscription.

Note: A PDF of our full paper follows the jump.