Hits and Misses

A new analysis of the historical performance of International Energy Agency scenarios

The term “scenario” was introduced by a group of researchers at the RAND Corporation in the 1960s. Herman Kahn explained its origin in 1979:

“We deliberately chose the word [scenario] to deglamorize the concept . . . There is no a priori concept that a scenario should be taken seriously or that it is intended to reflect aspects of the real world. Some scenarios do, others do not. Scenarios are simply a more or less imaginative sequence of events that are put together so that each event forms a context for the other events and so that there is some continuity over time in the “narrative.”

Energy scenarios created to inform policy are thus not forecasts or predictions, but “attempts to describe in some detail a hypothetical sequence of events that could plausibly lead to the situation envisaged.” Even though scenarios are not forecasts, if they are to be practically useful, then they necessarily must have some degree of plausibility.

An important paper just published — Lopez et al. 2025, Paving the way towards a sustainable future or lagging behind? An ex-post analysis of the International Energy Agency's World Energy Outlook — quantifies how the scenarios of the International Energy Agency’s (IEA) World Energy Outlook (WEO) compared to how the real world actually evolved, over the period 1993 to 2022.

Because IEA scenarios are not predictions, in any such exercise it is important to keep in mind that they are intended to project plausible futures — based on where we appear to be headed today — and desired (normative) futures, should we alter course. In addition, IEA scenarios are not independent of the futures that they project, in the case of the normative scenarios, explicitly so.

A comparison of the IEA’s scenarios with how the world actually evolved across key energy variables tells us a lot about how the IEA thought the world would and should evolve as much as it tells us about the IEA’s ability to imagine plausible futures. Of course, there is a lot of grey here, as effective decision making depends on some ability to foresee the consequences of taking one fork in the road over another.

With these nuances in mind, let’s take a look at some of the most interesting aspects of Lopez et al. 2025 — Note that below you will find my interpretations of their data, which may or may not agree with those of the paper’s authors.

Lopez et al. identify two types of scenarios produced by the IEA in its annual World Energy Outlook (WEO):

Outlook scenarios, those scenarios based on current policy developments

Normative scenarios, those that develop energy system pathways consistent with long-term goals such as the Paris Agreement

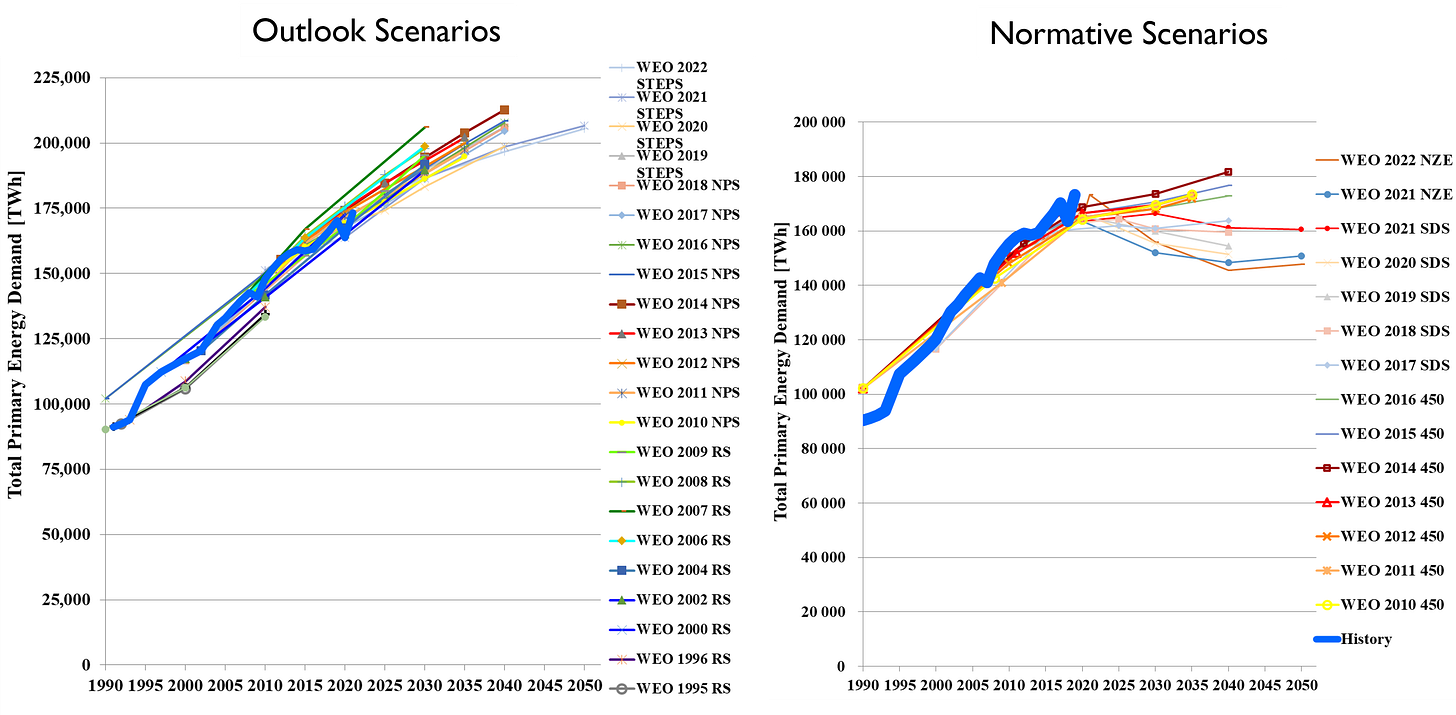

The figures below show IEA WEO scenarios for total global energy demand — for 1995 to 2022 for the outlook scenarios and 2010 to 2022 for the normative scenarios.

The outlook scenarios compare well with reality — which show a steady, almost linear and inexorable increase in global energy demand, punctuated only by the Global Financial Crisis and the COVID-19 pandemic. In contrast, the normative scenarios suggest a flattening of global energy demand, starting about 2020.

The real world has not followed the implications of the normative scenarios — specifically, that global energy demand should have peaked and even started a slow decline. I challenge the notion explicit in the IEA normative scenarios that we collectively should aim for a plateauing or decrease in energy demand. That is more like degrowth than energy abundance, which is notably absent in the range of IEA sustainability scenarios.

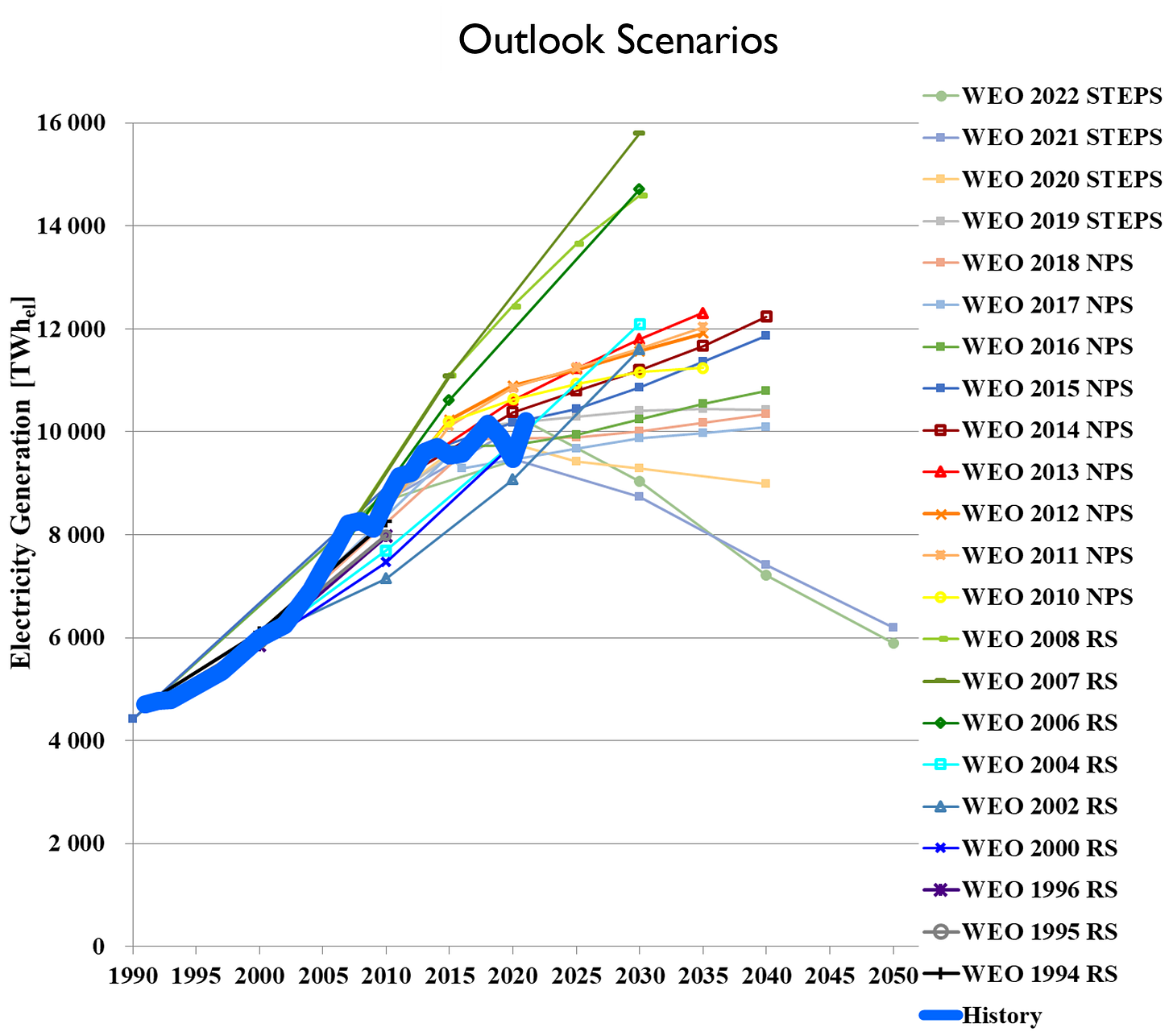

The IEA outlook scenarios for total global electricity generation for coal have several very interesting features, which you can see in the figure below.

First, note how the WEO scenarios in 2006-2008 project a massive increase in coal generation. This was the time period during which the so-called RCP scenarios of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) were being developed, including our old friend RCP8.5. The fever dream of a coal-fired future showed up in the IEA WEOs as well, but note how quickly the IEA pivoted off of extreme coal-fired futures — by 2010 the IEA had substantially reduced its coal projection. Ironically, that was one year before RCP8.5 showed up in the peer-reviewed literature.

Second, note how the 2020-2022 WEOs dramatically decreased projections of electricity generation from coal — and remember, these are the outlook scenarios, not the normative scenarios (the IEA WEO NZE 2021 and 2022 scenarios, not shown, have coal going to zero by as soon as 2040).

While the flaws in RCP8.5, and other scenarios that projected a “return to coal," were not documented comprehensively in the peer-reviewed literature until 2017 (in the great work by Justin Ritchie and Hadi Dowlatabadi) it is clear from Lopez et al. 2025 that even before the RCPs were completed and published, the energy modeling community well understood that extreme coal futures were not longer plausible.

The continued and widespread use of RCP8.5 (and the like) remains a scandal of gargantuan proportions in climate science.

Let’s take a quick look at two more interesting aspects of the IEA scenarios, both of which suggest a need to expand the scope of how we imagine plausible futures formalized in energy scenarios.

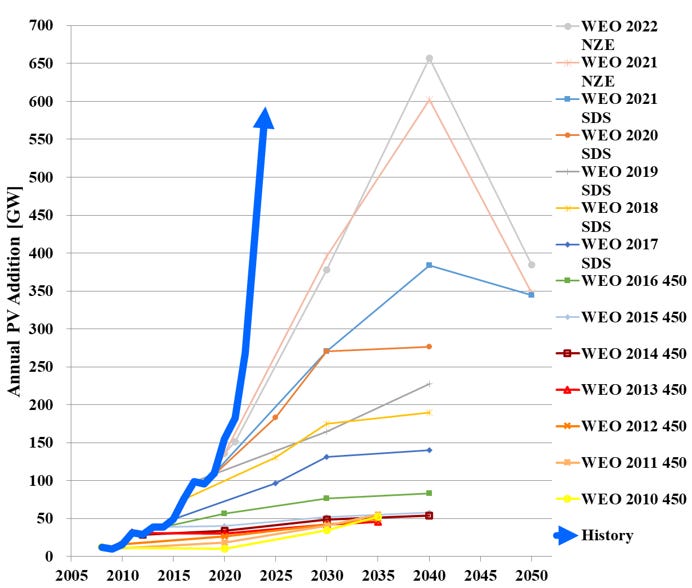

First, the figure below shows projected annual solar photovoltaic capacity additions in the IEA normative scenarios.

Reality has far exceeded projections, suggesting a fundamental inability to imagine the rapid technological and economic advances that underlie the remarkable pace of solar PV deployment. In such situations, exploratory scenarios (what if?) may be more valuable than scenarios based on today’s considerations of plausibility.

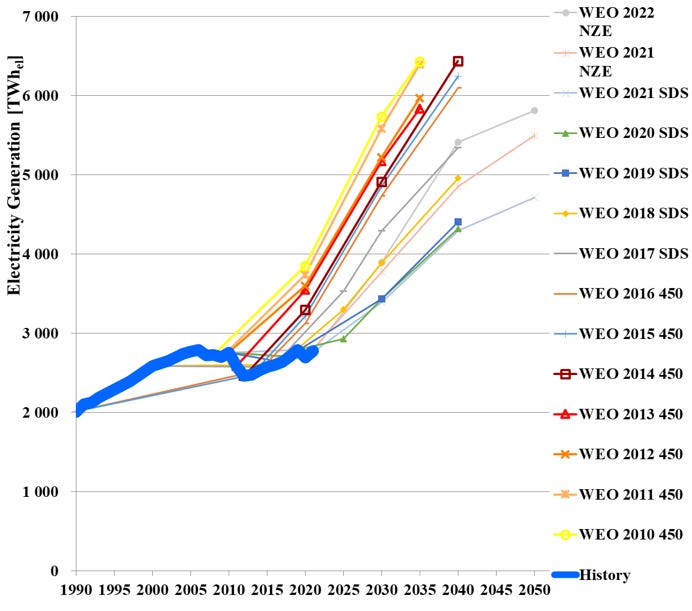

Second, the figure below shows total electricity generation from nuclear power in the IEA normative scenarios.

The IEA has consistently projected rapid growth in nuclear power in its normative scenarios — which would be necessary to achieve rapid rates of decarbonization. However, the real world has trailed all WEO normative scenarios since 2010. It may be that the IEA was not wrong, just too early, as there are today signs of a nuclear energy renaissance — we shall see.

The large gaps between reality and IEA normative scenarios on both solar and nuclear should motivate research to better understand why observed outcomes differ so markedly from scenarios. Is the gap due to policy? Technology? Economics? Or perhaps flawed scenarios? All of these?

Writing more than forty years ago W. Häfele, and H-H. Rogner offered important wisdom for thinking qualitatively about quantitative scenarios of energy futures:

“[M]athematical models serve as a brush for painting an overall picture whose observed pattern enhances ones understanding of what is plausible and what is not. It is for this reason that we consider such modeling a craft and not a science or an art.”

Lopez et al. provide all of their data in a very useful spreadsheet, which provides an incredible range of data on IEA WEO scenarios and real world data. The IEA updates its scenarios annually, which differs significantly from the IPCC, which updates its scenarios only about once every decade or so.

If scenarios are central to helping guide us into the future, then scenario evaluation and course correction are absolutely essential.

Comments welcomed!

The easiest thing you can do to support THB is to click that “♡ Like”. More likes mean that THB gets in front of more readers!

THB’s aim is to highlight data, analyses and commentary missing from public discussions of science, policy and politics — like what you just read above. A subscription costs ~$1.50 per week and keeps THB running so I can deliver posts like this to your in box several times a week. If you value THB and are able, please do support!

"The continued and widespread use of RCP8.5 (and the like) remains a scandal of gargantuan proportions in climate science."

This is true, but I suspect the primary reason for it is that the more dramatic the predictions of a climate study, the easier it becomes to get funding for subsequent studies. RCP 8.5's "We're all gonna die" is so much more interesting to largely non-technical readers than RCP 2.6's "there's nothing much to get worried about".

One of the major problems facing academia is the necessity of spending a significant portion of one's mental energy on obtaining funding, as opposed to doing the actual research work that the funding enables.

A scenario is essentially an act of the human imagination. It is presented in the form of an If… Then… statement. The description of this statement in the form of mathematical equations is then mistaken in the media for scientific fact.

These are no internationally recognized and enforced rules about how to judge and disqualify implausible scenarios. Anyone can use or invent any scenario they want, as an advocacy tool. Hence the longevity of RCP 8.5.

Does the inevitable, widespread misuse and misunderstanding of climate scenarios do more harm than good?