The short video above shows my talk on climate scenarios given at the 2022 IIASA Scenarios Forum, which was just posted this week. I previously discussed the content of my talk and shared some slides in this post. Since then, views on climate scenarios have continued to evolve as anticipated in my talk.

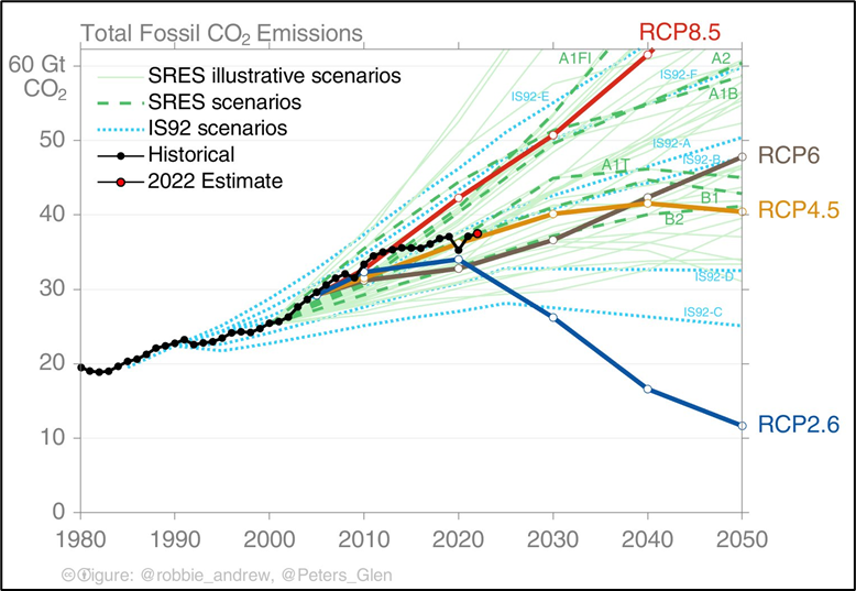

For instance, in the most recent release of the Global Carbon Project, total global carbon dioxide emissions in 2022 fall right on a commonly used scenario that has a radiative forcing of 4.5 watts per meter squared (w/m^2) in 2100. You can see this in the figure below.

A 4.5 W/m^2 scenario is important because it has been widely used in the academic literature and by the U.S. National Climate Assessment to indicate a future where climate policy is successful. That’s right. What was widely viewed just a few years ago as climate policy success (and, actually, still presented as success in the latest draft of the next U.S. NCA) is today more properly viewed as an upper bound on the evolution of global carbon dioxide emissions, at least for the foreseeable future.

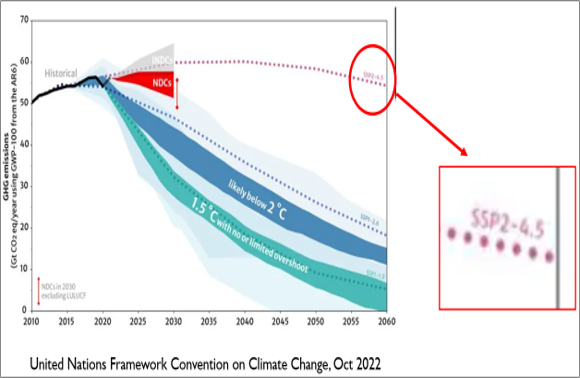

You can see this in the graph below from the U.N Framework Convention on Climate Change (which holds its annual Conference of Parties, or COPs, most recently a few weeks ago in Egypt). The graph shows projected global greenhouse gas emissions (including carbon dioxide) to 2030 as the red wedge. The graph also shows that the entire red wedge falls below a scenario called SSP2-4.5, which is a more recent version of a 4.5 W/m^2 radiative forcing scenario for 2100.

The good news in climate scenarios does not make the challenge of deep decarbonization any easier — it is truly huge and important. And as you can also see in the UN FCCC figure above, a 4.5 W/m^2 was never properly characterized as “success.”

But even so, there is very good news in latest understandings of climate scenarios and how they compare to the real world. We now know that the apocalyptic scenarios that have dominated climate science and policy discussions over the past decade+ no longer are plausible. Some have known this longer than others (such as my colleague Justin Ritchie who was on top of this many years ago and published early and the best peer-reviewed papers on the topic).

Of course, the future is uncertain and perhaps the apocalyptic scenarios will in the future return to plausibility — strangely, some seem to wish for this to happen. However, it is difficult to envision the circumstances for such a return to plausibility occurring anytime soon. Even so, letting go of apocalyptic scenarios still proves difficult.

Just yesterday the chair of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change was promoting the most extreme, implausible scenario as part of a call to climate advocacy. People might debate how much the IPCC should participate in advocacy, but one thing we should all be able to agree on is that the IPCC should stick to the best available science.

The climate discussion has entered a sort of bizzaro world where many continue to repeat outdated and incorrect science, perhaps because they view it to be politically useful or just though habit. I’m not worried. Good science will win out in the end. Even if that takes a while. All of us have a responsibility for helping to make that process happen a little faster.

Comments welcomed on my talk above and our papers below.

For further reading:

Ritchie, J., & Dowlatabadi, H. (2017). Why do climate change scenarios return to coal? Energy, 140:1276-1291. (PDF)

Pielke, Jr., R. (2018). Opening up the climate policy envelope. Issues in Science and Technology, 34:30-36.

Burgess, M. G., Ritchie, J., Shapland, J., & Pielke, Jr., R. (2020). IPCC baseline scenarios have over-projected CO2 emissions and economic growth. Environmental Research Letters, 16(1), 014016.

Pielke Jr, R., & Ritchie, J. (2021). Distorting the view of our climate future: The misuse and abuse of climate pathways and scenarios. Energy Research & Social Science, 72, 101890. (email me for a copy if paywalled)

Pielke Jr, R., & Ritchie, J. (2021). How Climate Scenarios Lost Touch With Reality. Issues in Science and Technology, 37(4), 74-83.

Pielke Jr, R., Burgess, M. G., & Ritchie, J. (2022). Plausible 2005-2050 emissions scenarios project between 2 and 3 degrees C of warming by 2100. Environmental Research Letters.

Please consider a like of this post or sharing it. Thank you!

Really like your last comments re good science will win in the end. Absolutely agree. My concern is that in the interim we will make decisions off of “bad science”, that could create more long term problems. We are already seeing this happen re fertilizer usage and food production. What happened in Sri Lanka could have been avoided.

thanks Roger. this post prompts me to ask a question ive been meaning to ask when reading your work for a while. What is your view on those who argue we are at risk of triggering 'runaway climate change'? The idea that negative feedback loops (ice loss, permafrost, fires etc) could trigger processors that lead to accelerated climate forcing etc and thus far more dramatic climate impacts. Suppose, for example, over next few decades we track more or less along SSP2-4.5, would humanity be at some risk (what risk) of this scenario? And if so, could this have 'apocalyptic' outcomes in the long run? How do you assess this kind of risk in general?