Five Things Everyone in Reinsurance Should Know

Understanding and managing risk is not just about numbers

It is renewal season in the catastrophe reinsurance industry, which is seeing demands for pricing increases based on sub-par performance for investors. According to S&P Global:

Even before [Hurricane] Ian, it was doubtful that the reinsurance industry would earn its cost of capital in 2022, largely because of a heavy year for natural catastrophe losses. Now, the industry is on track to deliver its sixth-consecutive set of sub-par annual results to investors, who were already doubting reinsurers' ability to price catastrophe risk.

Artemis, which covers the industry, asks how an industry based entirely on risk assessment and management finds itself in such a situation:

Reinsurers and insurance-linked securities (ILS) funds feel pricing has not kept up with loss costs, let alone inflation (economic or social), and has not accounted for the frequency seen, or the effects of secondary peril events, while climate change expectations have also not been factored in.

There is a question that needs asking as to how or why the industry has got itself into a position where, market-wide, the baseline price needs raising, so significantly in some regions?

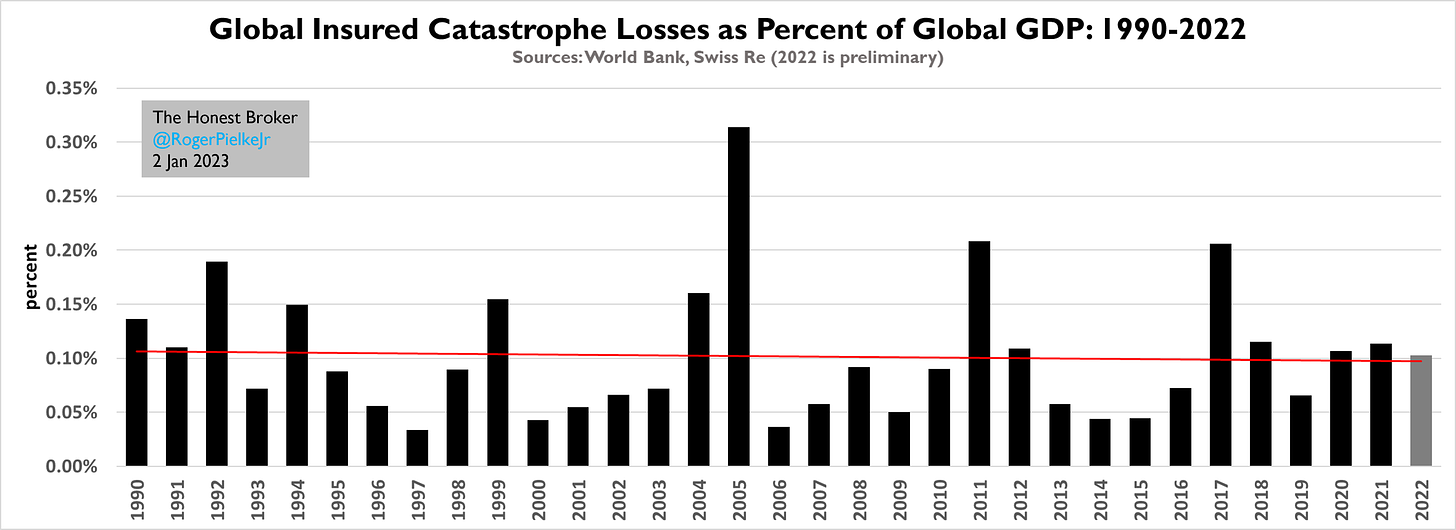

The figure below helps us to start answering this question. It shows global trends in insured catastrophe losses (excluding human-caused disasters) from 1990 to 2022.

There is no trend in insured catastrophe losses as a percent of global GDP, which suggests that over decades, the industry does an excellent job of managing its exposure and losses. However, if you focus in on just the past 15 years, since 2006, you’ll see that 9 of the 11 years from 2006 to 2016 were well below the long-term trend. That was due in large part to the great U.S. major hurricane “drought” which spanned exactly that period. Since 2017, insured losses have been above-trend in 5 of 6 years, including 2022. Regression to the mean can come as a shock.

I’ve conducted research on catastrophes for decades and based on that work and occasional interaction with those in the industry, I suggest the following five lessons that everyone in the reinsurance industry should know. For some, these five lessons many not be anything new, but in my experience, for others they are often underappreciated.

U.S. Major Hurricanes are the Biggest and Best-Known Risk, But Make Sure You Actually Understand that Risk

In a detailed decomposition of the Munich Re catastrophe loss database in 2014, Shali Mohleji and I calculated that U.S. hurricanes were not only the largest component of “global” insured losses, but also represented the majority (~60%) of the increase in “global” insured losses from 1980 to 2008. That means that U.S. hurricane losses have become even more important over time as a driver of losses for the global industry.

During the major hurricane drought of 2006-2016, this growth in losses resulting from U.S. hurricanes slowed down due to the lack of major losses, but picked right back up again in 2017. What the reinsurance industry has experienced over the past 6 years is much closer to “normal” than the previous decade. People who have been in the industry for many decades will likely appreciate this longer-term perspective.

Secondary Perils are Primary Risks

If U.S. hurricanes are the best known risk — and by far, I’d argue — then that necessarily means that we know less about everything else. That means that fire, flood, tornado, hail, earthquake and more. Any company that thinks that they are improving their risk profile by deemphasizing U.S. hurricane exposure and replacing it with exposure to other hazards in other locations around the world may be in for a rude surprise. All they may be doing is exchanging a known large risk for risks accompanied lesser known magnitude and frequency, as well as exposure and vulnerability. A good trade off?

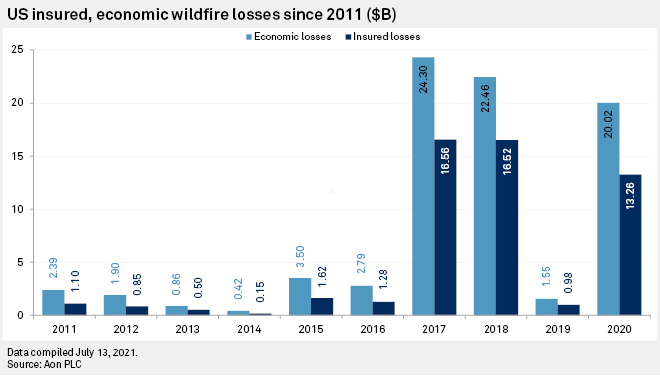

The image above illustrates this dynamic with U.S. insured wildfire losses, which were pretty benign until 2017, when losses approached the totals typically seen in hurricanes.

In modeling done after the 2017 and 2018 fire seasons and summarized in the figure above, AIR warned, “None of these recent U.S. wildfires, therefore, are considered tail events—rare events with high losses. Instead, these events have low return periods of less than 100 years, which reflects increasing U.S. wildfire risk, in large part due to development of the wildland-urban interface.” Risks are always must easier to see looking in the rear-view mirror.

Catastrophe Modeling Reveals and Creates Risk

Catastrophe models are essential tools for assessing risk and they should not to be confused with the recent development of so-called climate analytics built on climate change scenarios. However, catastrophe models have significant limitations and if not properly used, can create risks as well as reveal them.

The figure below comes from a paper I did with Jessica Weinkle (in 2017 — “The Truthiness about Hurricane Catastrophe Models”) and shows various estimates by catastrophe modelers for the contemporary “probably maximum loss” for hurricanes in Florida, taken taken from their submissions to the Florida commission that regulates the models.

We explained that the broad range of uncertainty estimates opens up a wide range of interpretations:

[A] risk manager could—with 95 percent statistical confidence—select any value between US$33 and US$192 billion as an accurate and scientifically valid estimate of hurricane risk for the given portfolio . . .

Catastrophe models allow us to make educated guesses of financial risks based on data on exposure, vulnerability and hazard. They are best understood as qualitative tools that lend themselves to quantitative misinterpretation. They are most accurate in the aftermath of a specific event, in part because the hazard part becomes certain. Using catastrophe models effectively is a bit like being a good poker player — it is not enough to understand math, you also have to understand the math in context of its application.

Risk Assessments are Always Out of Date

The Tweet above comes from Steven M. Strader who routinely posts fascinating visualizations showing the “expanding bullseye effect,” which he has explored along with Walker S. Ashley. They explain:

[T]he expanding bull’s-eye can be thought of as an archery target, where inner rings are made up of people and their possessions, and arrows symbolize hazard events. Unlike real archery, the expanding bull’s-eye target rings enlarge over time. This amplification results in a greater likelihood of arrows hitting an inner ring on the target. Accordingly, as population continues to grow and expand, the chance that a hazard impacts developed land, resulting in a disaster, increases.

In my experience, in reinsurance a lot of attention is focused on the hazard element of catastrophe losses — how many events? how severe? what will climate change do? — and much less on understanding exposure and vulnerability. Society changes must faster than even the most aggressive projections of climate change, and that means that estimates of risk that are not using the most up-to-date and accurate information on exposure and vulnerability will likely result in flawed risk estimates.

One other important point — Our knowledge of hazard futures is fundamentally limited, no one can tell you where next year’s hurricanes will hit. However, our knowledge of exposure and vulnerability is limited only by our willingness to expend the resources necessary to measure them.

History, Experience and Common Sense Remain Your Best Tools

Effective reinsurance practices like other forms of finance requires a combination of skill and judgment. On the short-term (annual or multi-year) reinsurance may seem a bit like gambling, and the same could be said for other types of investment. But like gambling, smart reinsurance means that while not every decision will prove a winner, good decision making means that the house always wins.

A challenge however is that the real world can confound expectations longer than some businesses can stay solvent. That is one reason why the giants in reinsurance — like Munich Re and Swiss Re — consistently post strong profits, they can play for the long-term. Just like the extended major U.S. hurricane “drought” boosted reinsurance earnings for a spell and likely made a lot of people look smart, the opposite could just as easily occur. For instance, there could be an extended period of major hurricane landfalls (are we actually in one now?) or a series of big earthquakes.

Knowing what we know, what we can know and what we cannot, and making decisions robust to uncertainty and fundamental ignorance is what has made reinsurance so successful for more than a century. With a good understanding of history and the lessons of experience, the industry will come though today’s challenges as well and be well positioned to support society in an era of climate uncertainty and change.

Recommended reading

Ashley, W. S., & Strader, S. M. (2016). Recipe for disaster: How the dynamic ingredients of risk and exposure are changing the tornado disaster landscape. Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society, 97(5), 767-786.

Mohleji, S., & Pielke Jr, R. (2014). Reconciliation of trends in global and regional economic losses from weather events: 1980–2008. Natural Hazards Review, 15(4), 04014009.

Pielke Jr, R. A. (2009). United States hurricane landfalls and damages: Can one-to five-year predictions beat climatology?. Environmental Hazards, 8(3), 187-200.

Weinkle, J., & Pielke Jr, R. (2017). The truthiness about hurricane catastrophe models. Science, Technology, & Human Values, 42(4), 547-576.

Weinkle, J. (2020). Experts, regulatory capture, and the “governor's dilemma”: The politics of hurricane risk science and insurance. Regulation & Governance, 14(4), 637-652.

Very interesting Roger, thank you.

I guess the part that strikes me as the most alarming is that humans continue build society in places where the probability of destruction is the highest. And this flies in the face of the many who see mitigation as one of the key pillars in this on going saga. In my humble opinion, I believe that the “mitigation” advocates need to begin screaming from the roof tops. Much like those who favor decarbonizing.

It is a consistent issue that increased re/insurance pricing is cast as an outcome of losses and not also related to investment performance. Both sides of the insurance business matter for broad understanding of costs.