Do U.S. Presidents Matter for Carbon Dioxide Emissions Reduction?

The answer is not what most people will expect

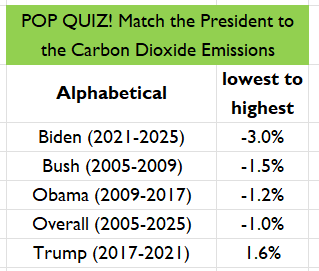

Pop Quiz!

Before reading on, please provide your best guesses matching the presidential administration with with the annual rate of carbon dioxide emissions reductions over each president’s term in office — dating to 2005, which is the baseline year commonly used to assess U.S. emissions reduction progress.

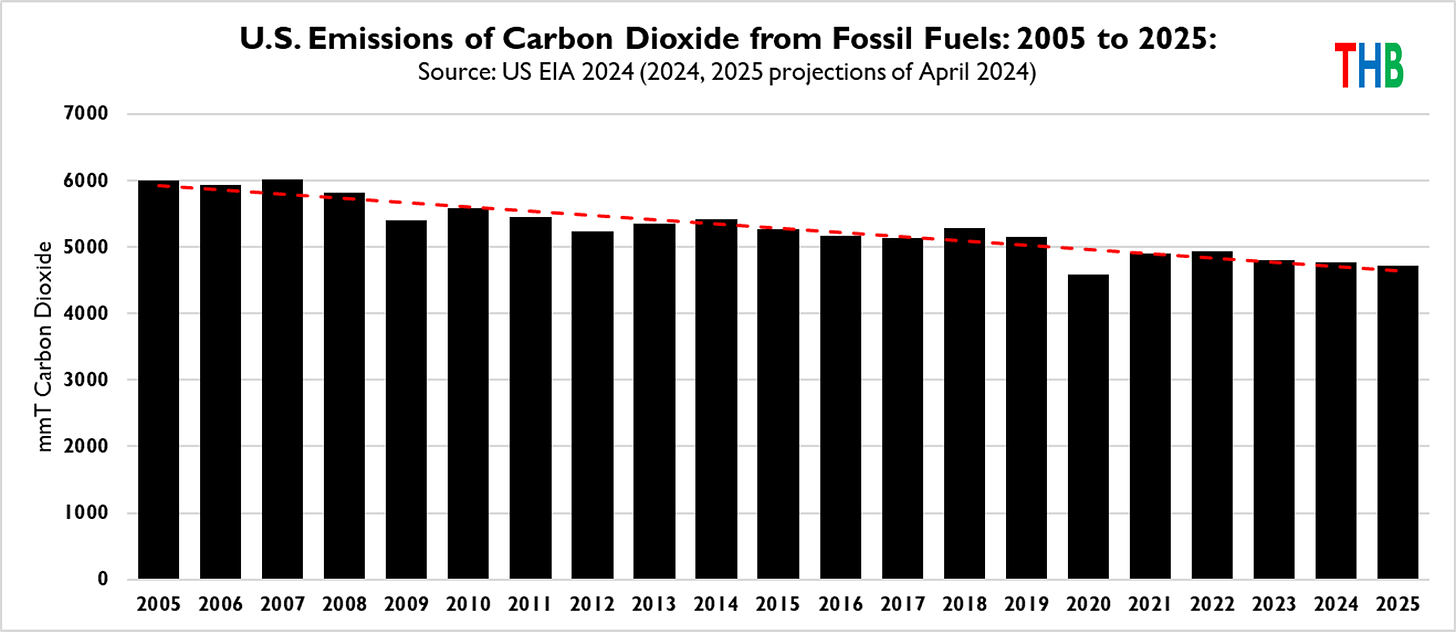

I’ll provide the answers after sharing some data. The figure below shows overall U.S. carbon dioxide emissions from 2005 to 2025 (with 2024 and 2025 estimated in April 2024, via the outstanding U.S. Energy Information Agency).

You can see that over the past two decades U.S. emissions have declined very steadily, with notable departures in 2009 (Global Financial Crisis, GFC) and 2020 (COVID-19 pandemic) only to snap back more or less on trend. The steadiness of the decline is remarkable given that these two decades saw two U.S. presidents who championed emissions reductions (Obama and Biden) and two who did not (Bush and Trump).

This raises a question: How much do U.S. presidents matter for the annual pace of emissions reductions?

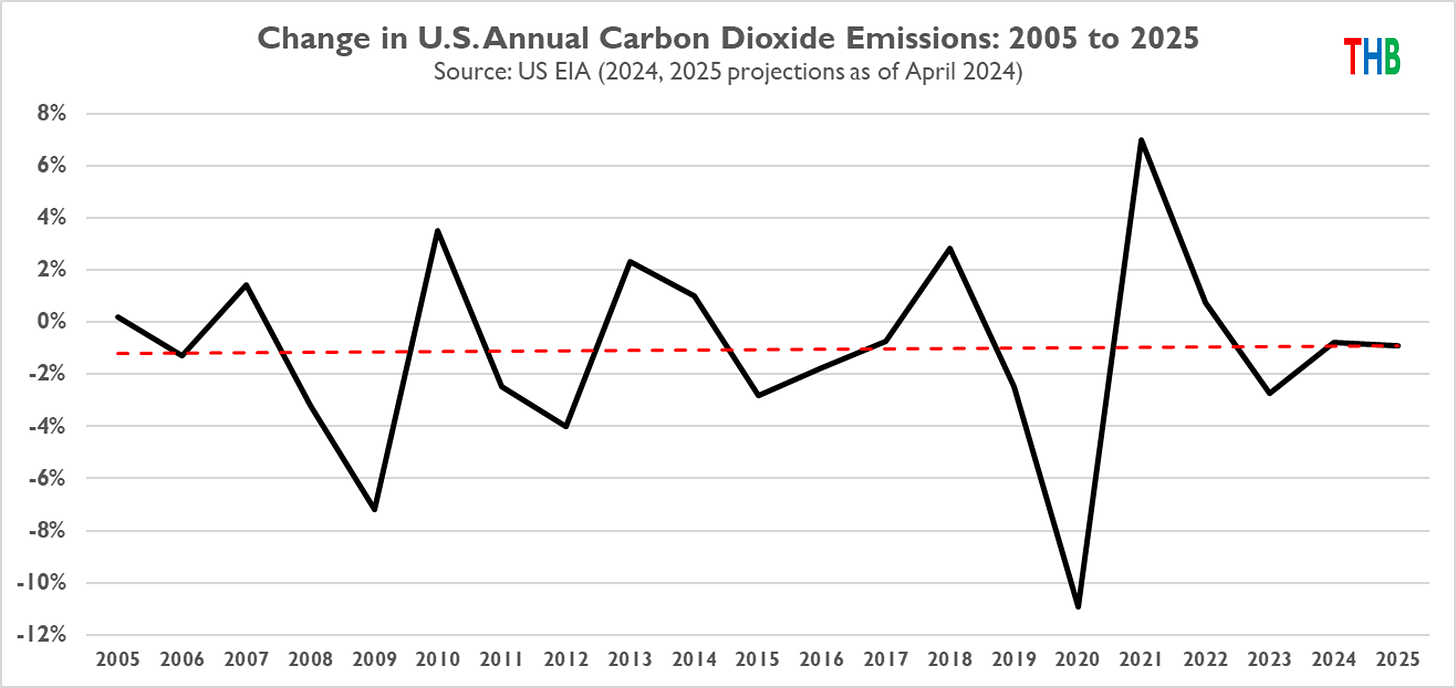

To get a better sense of the answer to this question, let’s look at annual rates of changes in emissions, shown in the figure below.

The biggest year-on-year changes were the years of the GFC and COVID-19, and respective bounce backs in the years following. The overall growth rate is negative, which is why U.S. emissions have decreased since 2005. But of note, there is no trend at all in the rate of change in that decline. There is no evidence of an acceleration in emissions reductions, due to policy or anything else, and no such indication is expected in the data before 2026.

Three years ago, the Biden Administration announced a target of reducing greenhouse gas emissions by 50-52% from 2005 levels by 2030. Over the three full years to date of the Biden Administration, U.S. emissions have increased by ~1.6% per year (though that does include the pandemic recovery). If we include current EIA projections for 2024, then the Biden Administration will finish its first term with an overall increase in emissions of 1.0% per year, with 2024 seeing a year-on-year decrease of 0.8%.

Going forward, to meet the Biden Administration’s 2030 emissions reduction target will require annual emissions reductions of ~8-9%, and this number goes up every year that these reductions are not achieved. The Biden Administration’s expected emissions reductions in 2024 are off the rate implied by its 2030 target by a factor of 10 or more.

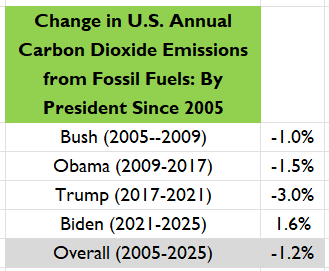

So let’s provide the answers to the pop quiz. How do U.S. annual carbon dioxide emissions reductions stack up by president?

The data show two presidents were below trend — Obama and Trump, and two were above trend — Bush and Biden.

One interpretation of these data would be that presidential administrations do not matter for annual U.S. emissions reductions. This is correct up to a point and especially for the short period that each leader is in office.

The GFC and pandemic both illustrate that even the U.S. president is at the mercy of national and global economic forces. Such forces are present, if not so dramatic, even in years that are not crises. Breaking news — There is actually no control knob in the White House Situation Room labelled “carbon dioxide emissions.”

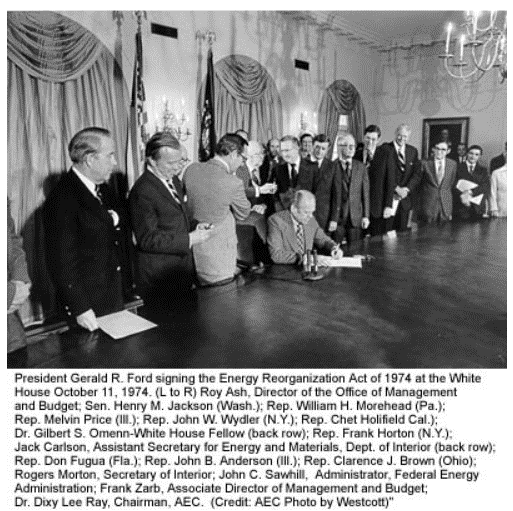

There is an important nuance here — Presidential administrations and national energy policy do matter for annual changes in carbon dioxide emissions, but over much longer terms than individual presidential administrations. The emissions reductions from 2005 to 2025 did not happen by magic or due to the fictional “free market.” Rather, they happened because of policies put into place many decades ago and with the partnership of many corporations in the energy sector, and across all technologies.

I’ll cite three examples, each of which played an important role in the observed U.S. emissions reductions from 2005.

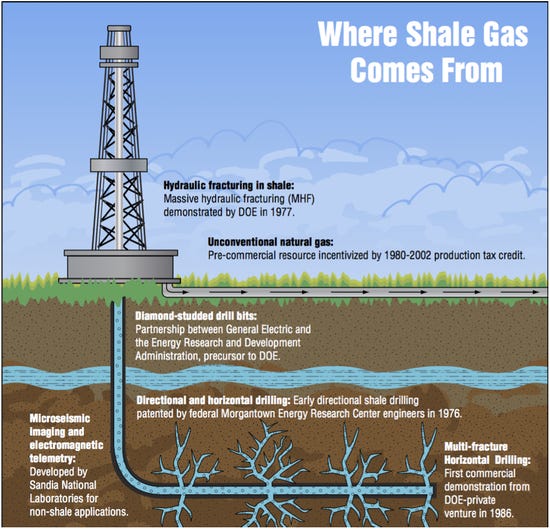

The first is fracking technologies, which were the result of many decades of public-private partnerships dating to the 1970s, as documented by The Breakthrough Institute in this excellent 2012 report. The second is wind technology, which received federal and state investment tax credits in the 1980s and production tax credits later, helping to jump-start the industry and survive market ups and downs over the decades that followed (see this 2008 Congressional Research Service Report). The third example is solar technology, which has been a focus of federal R&D investments for more than 50 years, though perhaps not at the levels many — including me — would have liked.1

Carbon dioxide emissions are the result of the burning of fossil fuels. They are not reduced through the short-term deployment of wind and solar energy production technologies. They are not reduced by simply spending money on R&D. They are also not reduced by political targets.

Carbon dioxide emissions are reduced through the three Rs:

Retirement = Shuttering of coal plants

Replacement = Coal to nuclear, EVs that displace ICEs, incandescent to LEDs

Reduction = Reducing flaring and methane leakage, gas generation replacing coal

The three “Rs” are not particularly amenable to change on timescales of individual Congresses, presidential administrations, and perhaps not even over decades spanning considerable political change. For instance, embarking on a policy to site new nuclear power at current or legacy coal plants — a no-brainer if there ever was one — could not be done by 2030, but perhaps 2040 and certainly by 2050.

National energy policy necessarily must look far into the future — it is more like planning for the solvency of Social Security, building an interstate highway system, or equipping the U.S. military. Energy policy is also not just about policy or just the private sector, but both working together.

National energy policy also includes many more dimensions than just carbon dioxide emissions, which are important to be sure, but not everything. These other dimensions include affordability, reliability, accessibility as well as trade, national security, and geopolitical dynamics. Energy policy also needs to consider environmental impacts beyond climate.

The bottom line: Presidents do matter a great deal for energy policies and their outcomes, and thus for carbon dioxide emissions. A comprehensive U.S. energy policy needs to carefully consider those dimensions of energy policy that can be influenced on short time scales within an administration’s term, those dimensions that necessarily require a longer-term perspective, and not to confuse the two — regardless the political pressures.

❤️Click the heart if you aced the pop quiz or if you wished you did!

Thanks for reading! THB is reader supported. You make make it possible. Please share, comment, critique, converse and I appreciate your support at whatever level makes sense for you. Learn more about THB here.

As an aside, Frank Laird of the University of Denver documents that Republicans were the early champions of solar during the Cold War, illustrating that the champions of technologies can change their minds over longer terms. Technologies have politics and those politics are subject to change.

I'm not sure what you mean by the "fictional" free market. I hope you mean that our energy markets are not free markets because of massive interference by the government -- including insane regulations holding back nuclear, subsidies for unreliables like wind and solar, and so on. The concept of free markets is far from fictional. It's something we should fight hard to move closer to.

I found this article to be a muddle. Early in the article

"One interpretation of these data would be that presidential administrations do not matter for annual U.S. emissions reductions. This is correct up to a point and especially for the short period that each leader is in office."

Then the last paragraph

"The bottom line: Presidents do matter a great deal for energy policies and their outcomes, and thus for carbon dioxide emissions. A comprehensive U.S. energy policy needs to carefully consider those dimensions of energy policy that can be influenced on short time scales within an administration’s term, those dimensions that necessarily require a longer-term perspective, and not to confuse the two — regardless the political pressures."

Why should energy policy consider those dimensions that can be influenced on short time scales within a president's term? That is short term thinking, like asking how many miles of roads were built in a president's term.

Rather than looking at personalities (presidents) we should consider which policies produced good results. Considering personal factors is the same fallacy often used when looking at GDP growth in a president's term. GDP, like energy, is influenced by policies, not personalities.