Scenarios are fundamental to climate research and policy. As THB readers know better than most everyone, for years climate science and policy have been off track in relying heavily on an outdated extreme emissions scenario called RCP8.5, one of four RCP scenarios developed starting almost two decades ago.1

Some in the climate science community, though slow out of the blocks, have come around to recognize that extreme scenarios should not be prioritized in climate research to inform policy. In a paper published last week,2 a group of experts in scenarios and scenario-based research gave advice, requested by the climate modeling community, for the next generation of scenarios and they concluded that high emissions scenarios be given “lower priority.”3

However, the scientists in the earth system modeling community who received that advice and are deciding upon the next generation of scenarios have rejected that advice, and have instead chosen — again — to assign the most extreme scenario its highest priority.4

The climate science community is thus on course to repeat the RCP8.5 debacle all over again, putting at risk the ability of climate research to effectively inform policy and the credibility of climate science.

Let’s get into some of the details.

To assess if a scenario is plausible requires assessing whether the assumptions that go into its development are plausible. For instance, we know that RCP8.5 and similar extreme scenarios are implausible (thanks to the excellent work of Justin Ritchie) because they project that the global energy system will “return to coal'“ requiring a massive expansion of global coal consumption. That has not happened and is not going to happen for the foreseeable future.

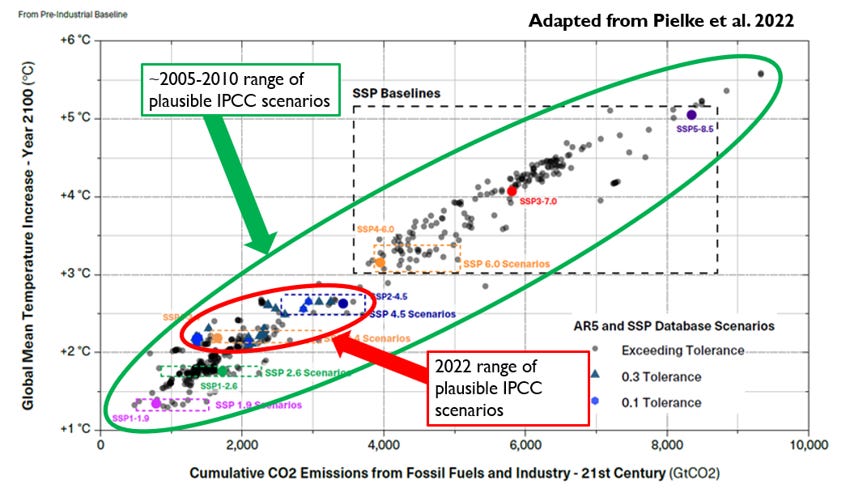

In 2022, Justin, Matt Burgess, and I compared climate scenarios to history and near-term energy projections to assess which were still plausible and which had departed from reality.5 You can see in the figure below that the range of plausible scenarios has narrowed significantly over recent decades, with projected 2100 global average temperatures of plausible scenarios (as of 2022) falling into the range of 2-3 Celsius, consistent with most other recent studies.6

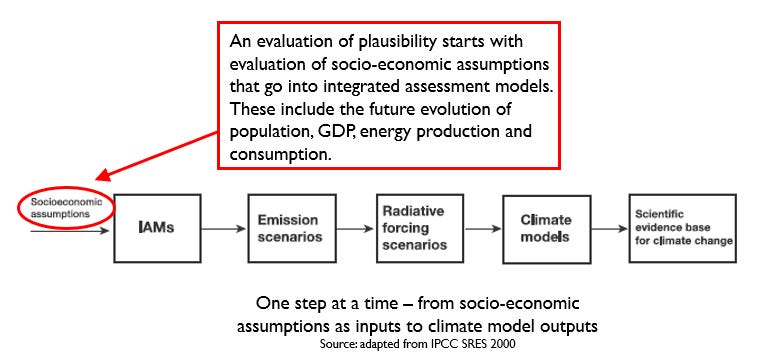

In 2000, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) explained that the development of plausible scenarios starts with an evaluation of socio-economic assumptions as a first step in a sequential process that ends with climate model outputs, as shown below.

When the RCPs were developed, climate modelers expressed impatience with the linear process that was a precursor to their ability to model the earth system. The subsequent decoupling of socio-economic assumptions from climate model inputs was a fateful mistake that allowed the implausible RCP8.5 to become the focus of climate research and policy.

Justin Ritchie and I explained in 2021:

“As climate model experiments broke away from these archetypal IAM scenarios, there was no longer a definitive means to assess the plausibility of specific RCPs - they quickly became central to climate research and assessment without an accompanying mechanism to evaluate plausibility and consistency.”

Surely the climate science community would not again in 2024 repeat the mistake of decoupling plausibility from scenario selection and prioritization?

Think again. Last week the climate science community doubled-down on such a decoupling — Meinshausen et al. 2024 call for a new family of Representative Emissions Scenarios (REPs to replace the RCPs):

“we argue that the REPs should remain separated from the underlying socioeconomic scenarios as was done previously under the RCPs”

Just as happened with the RCPs questions of scenario plausibility and consistency are something that is to be pushed off into the future, and someone else’s job, with a call for:

“a renewed effort to cross-examine each of the future climate change levels under a broad range of socioeconomic futures. At this stage, while developing REPs as input forcings for ESMs, it is not necessary to finalise or pre-empt the scope of socioeconomic futures and national level scenarios, given the importance of exploring a greater diversity thereof. A task of future IPCC reports will be to reflect the whole spectrum of research on socioeconomic futures and national scenarios.”

At this point in reading this post it would be appropriate to hear John McEnroe in your head exclaiming, “You cannot be serious!”

Why would the climate science community choose not to evaluate scenario plausibility before choosing a set of scenarios that are supposed to be plausible?

One answer is that the interests of the earth system modeling community are in conflict with the needs of policy makers, and the modelers have decided to prioritize their interests over the needs of policy. It’d be nice if these interests were identical, but they are not — and to be fair, no one should expect a group of scientists to decide their priorities any differently.

The scenario experts are aware of this conflict in priorities, explaining that (emphasis added),

“The impression could arise that the policy and scientific objectives relevant to the framing pathways are in conflict. While a policy-relevant question almost always entails a scientific question of interest, the scientific realm of questions is broader.”

They explain that the needs of earth system modeling mean that climate scientists do not want to wait for a plausibility evaluation (but why they have chosen to ignore the existing literature on scenario plausibility is a question that might be asked):

“The need to coalesce on a set of framing climate pathways for the ESMs [Earth System Models] only arises due to the ESMs’ multi-year lead times and high computational costs (Moss et al., 2010).”7

For its part, the earth system modelers are very clear that research priorities come first, policy input second. This is explicit in their description of their priorities for new scenarios:

Scenarios represent a critical tool in climate change analysis. They are used by different research communities to explore potential future avenues in socio-economic conditions, assess the effects of different drivers of climate change, characterize future climatic conditions, and assess impacts of climate change as well as adaptation and mitigation responses. Scenarios also connect these research communities. In this paper, we are specifically concerned with those scenarios that are used as external forcings to climate models, i.e. Earth System Models (ESMs), General Circulation Models (GCMs), Climate Models of Intermediate or Reduced Complexity (CMICs) and Simple Climate Models (SCMs). These external forcings encompass elements such as emissions and atmospheric concentrations of greenhouse gases, chemically reactive gases, and aerosols, and land use. Such scenarios play a pivotal role not only in climate research but as integrating tools for scientific assessment processes and policy analysis.

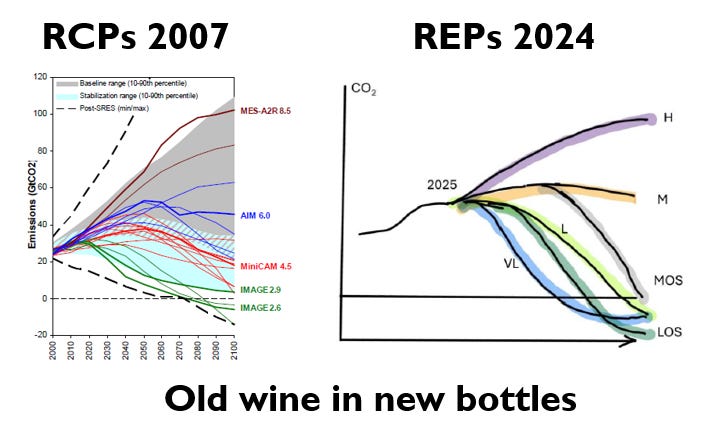

The image below shows the proposed new scenarios — REPs, idealized on the right — compared with the outdated RCPs on the left. If they look pretty much the same, well they are. The 2007 RCPs spanned a radiative forcing of 2.6 to 8.5 watts per meter-squared and the proposed new 2024 REPs span a proposed 2.0 to 7.0 watts per meter-squared. In the middle of each is 4.5 watts per meter-squared, which is above a “current policies” trajectory.

The climate modeling community is aware that the plausibility of the highest and lowest scenarios has been questioned:

“Also, over time, critiques emerged about the plausibility of some scenarios (SSP5-8.5 and its precursor, RCP8.5; SSP1-1.9).”

Yet, they have identified the highest priority scenarios to be a very high and a very low emissions scenario — those that have the lowest plausibility.

Similarly, there is a huge gap between very low scenarios and “frozen policies” — the orange one in the middle below, that assumes no policy changes from 2024. Incredibly and bafflingly, there are no scenarios proposed in what is arguably the most plausible range of futures.

How to fix this situation?

One step would be to decouple exploratory scenarios of interest to the modeling community from those relevant to the needs of policy makers. The science-focused scenarios should be labeled as exploratory, so as not to conflate scientific exploration with policy relevance. Of course, assertions of the policy relevance of science-focused scenarios provide a compelling justification for funding and a role for modelers in climate politics and advocacy.

Even though the earth system modelers claimed that plausibility should be evaluated by others, they still engaged in ad hoc plausibility justifications, in the complete absence of any analysis. Here is part of their justification why extremely high emissions scenarios should be prioritized in policy:

The scenario includes events and outcomes that may not be likely given current trends but are still plausible enough to occur. The world view it represents is consistent with policy roll-back, the lack of coordination and cooperation for addressing global environmental concerns, societies and industries depending on and even reverting to fossil fuel resources, the adoption of resource and energy intensive production technologies and lifestyles, and unforeseen technological barriers. This scenario is not meant to represent a “business-as-usual” or no-policy reference scenario for the other cases. The scenario is intended to explore the upper end of GHG emissions resulting from deep political, technological and structural deviation from current trends.

Perhaps interesting and fun, but an exploration of the climate consequences of deep “political, technological and structural deviation from current trends” — all in a negative direction — is of less relevance to policy makers than scenarios that explore where we think we are actually headed in the coming years and decades.

The real justification for extreme scenarios here is of course not policy relevance but that the extreme scenario enables some cool science, as they explain:

“Allows direct comparison of new generation of ESMs with ESMs of the previous generation, if a CMIP6 high-end pathway is repeated (SSP5-8.5 or SSP3-7.0)”

“High signal-to-noise ratio for projected changes in climate to learn about climate system properties, if the system is “pushed hard””

Even better would be a return to the IPCC SRES (2000) approach which eschewed judgements of scenario likelihood and simply produced a very wide range of plausible futures, conditioned on alternative choices and development pathways. The future is a wide open place, where we go is up to us.

Few people realize that the next several decades of climate science — and thus peer reviewed research, media coverage, climate advocacy, climate policy — are now being determined8 by a very small group of researchers, with a very narrow range of disciplinary expertise, without any underlying research on scenario plausibility or utility in decision making, and all (or nearly all) from the rich parts of the world, notably the U.S., U.K and Europe.9

Climate scenarios have developed such that they have important roles in decisions that affect everyone on the planet. The scenarios are too important to be left to an ad hoc group of researchers designing them to serve their research. A new approach is needed, and fast.

We are on the cusp of having REP-7.0 take over from RCP8.5, with the same negative consequences for research and policy and for the next decade or more. Can we change course before it is too late?

❤️Click the heart for good science!

Thanks for reading! Below, paid THB subscribers can download Pielke and Ritchie (2021) which is a magnum opus on scenario development and how the community went badly off course with the RCPs and SSPs. I welcome your comments, questions, and discussion.