Climate Policy Rethink

Three new papers tell us that we need to immediately reconsider climate targets, equity, and scenarios

Last week three new analyses were published that together should help to motivate a much-needed rethink of climate policy. They are:

An essay by Vaclav Smil on the prospects for net-zero carbon dioxide by 2050, shared along with Michael Cembalest’s Annual Energy Paper for J.P Morgan;1

“Equity assessment of global mitigation pathways in the IPCC Sixth Assessment Report,” by Tejal Kanitkar and colleagues (preprint here for those paywall blocked);

and “Coal transitions—part 2: phase-out dynamics in global long-term mitigation scenarios,” by Jan Minx and colleagues (see their Part 1 here).

These three papers tell us that:

Climate policy targets and timetables need revisiting as the Paris Agreement targets are infeasible;

Global equity needs to be considered with equal (or even greater) priority than emissions reductions;

Scenarios that guide climate policy are biased towards the expansion of coal energy, misleading us in many ways, and in particular, away from the lowest hanging fruit.

Let’s take a closer look at each.

Smil reminds us that we are now past the halfway point between the Kyoto Protocol and 2050. He summarizes our climate policy accomplishments:

All we have managed to do halfway through the intended grand global energy transition is a small relative decline in the share of fossil fuel in the world’s primary energy consumption—from nearly 86 percent in 1997 to about 82 percent in 2022. But this marginal relative retreat has been accompanied by a massive absolute increase in fossil fuel combustion: in 2022 the world consumed nearly 55 percent more energy locked in fossil carbon than it did in 1997.

I won’t go into all the details — but you should, it is a Smil masterclass. Smil concludes:

Given the fact that we have yet to reach the global carbon emission peak (or a plateau) and considering the necessarily gradual progress of several key technical solutions for decarbonization (from large-scale electricity storage to mass-scale hydrogen use), we cannot expect the world economy to become carbon-free by 2050. The goal may be desirable, but it remains unrealistic.

Smil also observes, correctly and undeniably, that “even the first grand energy transition still has not been completed more than two centuries after it began” — global energy consumption remains profoundly inequitable.

A landmark paper published last week by Tejal Kanitkar and colleagues2 indicates that across IPCC scenarios of climate policy “success,” global economic inequities increase in a proposed energy transition, as shown below — the rich get a lot richer, as the poor just a bit richer.

Kanitkar et al. point out the uncomfortable fact that all IPCC modeling teams3 can be found in the locations that the models say will/should get richer:

The projection of unequal outcomes across scenarios and scenario categories, and across all key variables is a matter of serious concern, especially when scenario results are directly used as inputs for climate policy.

A large majority of scenarios that are finally assessed in the IPCC 6th Assessment Report are submitted by modelling teams based in the global North. While this may not be the critical reason for scenarios to lack equity, the pervasiveness of the absence of equity raises serious questions about the lack of diversity in the model building community, including the absence of perspectives from the global South, and the transparency with which model results are assessed and reported by the IPCC.

The community’s failure to consider scenarios of equitable futures goes well beyond just the IPCC.

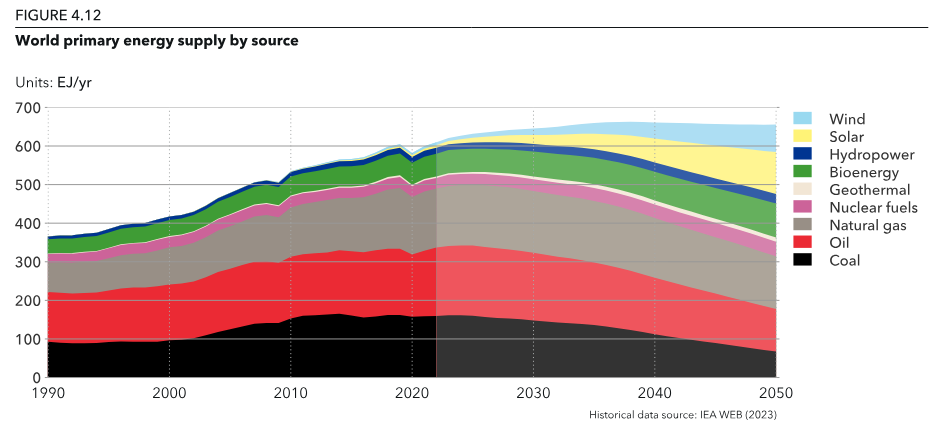

For instance, Smil points to the 2023 Energy Transition Outlook of the Norwegian DNV Group as offering a “realistic” projection of global energy futures to 2050, as compared to net-zero projections. The DNV projection has fossil fuels falling to 48% of total global energy consumption by 2050 (see figure below), and projects a global temperature increase of 2.2 degrees Celsius by 2100, just over the Paris Agreement target of 2.0C — consistent with our analysis of plausible climate scenarios.

Even so, the DNV admits that its projection “balances the fair and the plausible,” acknowledging that deep emissions reductions in its projections are “inconsistent with the notion of a just transition.” Even Smil’s example of a “realistic” projection to 2050 leaves behind much of the world’s population.

Another important new paper out last week — by Minx and colleagues — argues that IPCC climate scenarios continue to show a bias towards the assumed inexorable expansion of coal energy, unless climate policy stops it: “Remarkably, there is no SSP scenario that projects reductions in coal consumption independent of climate policy.” We now know that assumption across scenarios was wrong.

A coal-expansion bias was first documented by Justin Ritchie in several seminal papers, and the authors of the new study rightly recognizing Ritchie’s prescience. They also express surprise that the IPCC has not followed up on Ritchie’s (now “older”) work:

It is surprising that evidence on coal phase-out dynamics in long-term mitigation scenarios has not been assessed comprehensively in IPCC reports and only few older studies look at these dynamics in more detail (Ritchie and Dowlatabadi 2017a, 2017b).

The bias towards coal expansion underlying the models most influential in climate policy is important because phasing out coal is the single most important step that might be taken towards deep decarbonization — it is not even close. I’ve discussed the importance of phasing out coal often here at THB, see my pieces of a coal exit treaty, coal to nuclear, and low hanging fruit.

Minx et al. explain that coal-expansion bias actually gives us reason for greater optimism on the possibilities for phasing out coal, compared to the implications of the IPCC scenarios:

Our results further suggest that many models might over-estimate the efforts and costs of coal transitions in Paris-consistent mitigation scenarios. We find correlations between baseline coal consumption and mitigation costs for the associated policy scenario which suggests that assumptions leading to high coal consumption in baselines increase mitigation costs (figure S4). The majority of baselines expand coal consumption far beyond what would be expected from historical long-term trends.

The analyses of Smil, Kanitkar et al., and Minx et al. are profound because they imply that we need to rethink climate policy fundamentals, specifically:

Climate policy targets and timetables need to be revisited because those at the focus of policy analyses and implementation are infeasible (if technologically imaginable), even if they are readily achievable in stylized models and spreadsheets;

Global equity needs to be taken seriously in climate scenarios and projections. The reality is that for the world’s population as a whole, as Mike Hulme has written, “[T]here are some futures beyond 1.5 degrees C (or even 2 degrees C) that are more desirable than other futures which do not exceed these warming thresholds. We should not mistake one set for the other.”;

Climate policy alternatives and evaluation of those alternatives need to rely on a much broader base of models, methods, assumptions, and experts to open up possibilities and to avoid being trapped by myopia and mistake. This will mean loosening the grip of those few who have to-date dominated climate research, assessment, and policy.

In his essay, Smil warns us against being seduced by projections from modelers who foresee a “miraculous” reduction in fossil fuel consumption and urges more “responsible analyses”:

Wishful thinking or claiming otherwise should not be used or defended by saying that doing so represents “aspirational” goals. Responsible analyses must acknowledge existing energy, material, engineering, managerial, economic, and political realities. An impartial assessment of those resources indicates that it is extremely unlikely that the global energy system will be rid of all fossil carbon by 2050. Sensible policies and their vigorous pursuit will determine the actual degree of that dissociation, which might be as high as 60 or 65 percent. More and more people are recognizing these realities, and fewer are swayed by the incessant stream of miraculously downward-bending decarbonization scenarios so dear to demand modelers.

Smil concludes with a plea for pragmatism in climate policy and policy analyses:

Belief in near-miraculous tomorrows never goes away. Even now we can read declarations claiming that the world can rely solely on wind and PV by 2030 (Global100REStrategyGroup, 2023). And then there are repeated claims that all energy needs (from airplanes to steel smelting) can be supplied by cheap green hydrogen or by affordable nuclear fusion. What does this all accomplish besides filling print and screens with unrealizable claims? Instead, we should devote our efforts to charting realistic futures that consider our technical capabilities, our material supplies, our economic possibilities, and our social necessities— and then devise practical ways to achieve them. We can always strive to surpass them—a far better goal than setting ourselves up for repeated failures by clinging to unrealistic targets and impractical visions.

Amen to that.

Thanks for reading! I welcome your comments, questions, and alternative points of views. This post is in the tradition of Rayner’s “uncomfortable knowledge” because it directly challenges powerful institutions — through such challenges not only do we learn together, but we also open up space for more effective policy and politics. THB is supported by you, and I appreciate your support at whatever level makes sense!

I’ll have more on Cembalest’s report later this week.

In 2022, I characterized the pre-print version of Kanitkar et al. as the most important climate paper I read that year. It is the most important peer-reviewed paper I’ve read this year.

I call them “IPCC modeling teams” even though some will resist this designation. As Tejal Kanitkar observed on X/Twitter: “If modelers are simply sending in scenarios based on what they are asked to do by a "committee" that lies at the intersection of IAM modelers and IPCC authors, the IPCC must really rethink its stated position of being at arms length from the scenarios they assess.” See Pielke and Ritchie 2021 for a much deeper discussion.

Vaclav Smil claims: "... small relative decline in the share of fossil fuel in the world’s primary energy consumption—from nearly 86 percent in 1997 to about 82 percent in 2022..."

That is an erroneous statement. In actual fact it is much worse than that. The share of fossil fuel was actually 86.5% in 1997, 86.7% for combustion fuels, which are the carbon emitters. In 2022 it was 89.8%, 90.6% for combustion fuels. So we have gone backwards, both proportionally & absolutely, since Kyoto.

Smil is using BP data. They invented this scam of multiplying wind & solar by 2.6X for primary energy to make them look far higher than they really are while dividing nuclear by 1.2X making it look lower than it really is. You need to go to the IEA to get the correct data. Now why does BP want to hype up wind & solar while downplaying nuclear? Suspicious or what?

I enjoy the work but was lost as soon as equity was brought up. The bogeyman of unequal outcomes immediately means control systems put in place by well meaning bureaucrats and "intellectuals" who can't possibly understand the unintended outcomes from their hubris and good intentions. Why would we export such arrogance when it is demonstrably unworkable here. MA, NY, CA and a growing number of other left leaning states have plighted their green energy troth at the altar of identity and equity politics with bad outcomes. Massachusetts is a poster child for what happens when you remove all market forces from an industry sector - energy- and replace it with subsidies and penalties to "help" people, in this case blacks. Bureaucrats are going to help them all the way until they have nothing

Why not focus on recognizing the folly of "free energy" and understand that the reason carbon fuels win is because they are the single greatest indicator of economic growth in history. Every emerging growth economy has moved from 3rd world status because of available electricity and it carbon fuels. Forcing wind and solar on poor countries will most certainly not make them at all richer. It will impoverish them while rich multiculturalists in Manhattan, Silicon Valley, LA, DC, and elsewhere pat themselves on the back as they tool around in Lucids and Teslas.

If we want meaningful growth in poor regions we should run the other direction from "equitable practices" enforced by environmental governance fiat. The WHO's pure disregard for humanity amidst COVID is a perfect example of what happens when we allow an unrepentant chattering class try to fix things. I don't subscribe to drill baby drill in the least but ignoring the tradeoffs of various energy policies will wreck hard-fought gains that working poor countries have earned. We need to take away the massive subsidies given to energy producers that are part of failing policies and find alternatives that allow for continued growth at the least possible ecological cost.