Climate Journalism Done Right

The Washington Post: The Real Reason for Increasing Billion Dollar Disasters

Today, The Washington Post has published a lengthy analysis titled, “The real reason billion-dollar disasters like Hurricane Helene are growing more common.”1 The article, by the Post’s Harry Stevens, is brilliantly done — extensively reported, data rich, grounded in a large body of research, with a wide diversity of voices. Watching reactions to the article will be fascinating.2

Let’s take a look at Stevens’ analysis of the NOAA billion dollar disaster (BDD) tabulation and how it has been often mischaracterized in assessments and in policy.

Stevens opens by explaining why the disaster count matters — it is often invoked as a justification for policy:

The disaster data, maintained by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, has featured in multiple government reports on global warming. The Biden administration has referenced it at least seven times to help make the case for climate policies. Members of Congress cited it in a bill to curtail the use of fossil fuels. Last year’s National Climate Assessment, a congressionally mandated report on climate change, showed the disasters on a map under the heading “Climate Change Is Not Just a Problem for Future Generations, It’s a Problem Today.”

But according to disaster experts, former NOAA officials and peer-reviewed scientific studies, the chart says little about climate change. The truth lies elsewhere: Over time, migration to hazard-prone areas has increased, putting more people and property in harm’s way. Disasters are more expensive because there is more to destroy.

Read that again.

The Post reports some interesting details on the origins of the BDD dataset:

Neither of them can remember exactly when or whose idea it was, but some time in the early 1990s, Neal Lott and Tom Ross started tracking weather disasters in the United States that caused at least a billion dollars in economic losses. They scoured government reports and phoned insurance companies to compile their list. The job took up a small portion of their time working at what was then called the National Climatic Data Center.

“At that point, it was not an attempt to do any sort of a scientific study,” Lott said. “As far as climate change, that wasn’t in mind at all.”

Each year brought a longer list of disasters, but the two meteorologists did not think the weather had changed. Instead, they noticed there were more people and property in areas prone to natural hazards.

Tom Ross, the former NOAA official, has a great quote:

“It doesn’t take as much to get to a billion dollars now than it did 20 years ago .If a storm hiccups, it gets a billion dollars’ worth of damage now, whereas 20 years ago, it took a lot more than a hiccup to do it.”

The NOAA official currently responsible for assembling the BDD tabulation, and who has been in that role for more than a decade, offered a remarkable admission to the Post:

“We’ve never sought to do attribution studies in relation to the extremes listed in the billion-dollar disaster dataset.”

That means that all of the claims made by NOAA and public officials claiming that the increase in BDD counts has been driven by human-caused changes in the climatology of extreme weather are not grounded in any attribution analysis whatsoever.

The Post does a nice job situating our research in the broader context of their analysis — starting with me and NOAA’s Chris Landsea in the mid-1990s and later with many more wonderful colleagues. You can read about how our first paper on disaster normalization began on a basketball court.

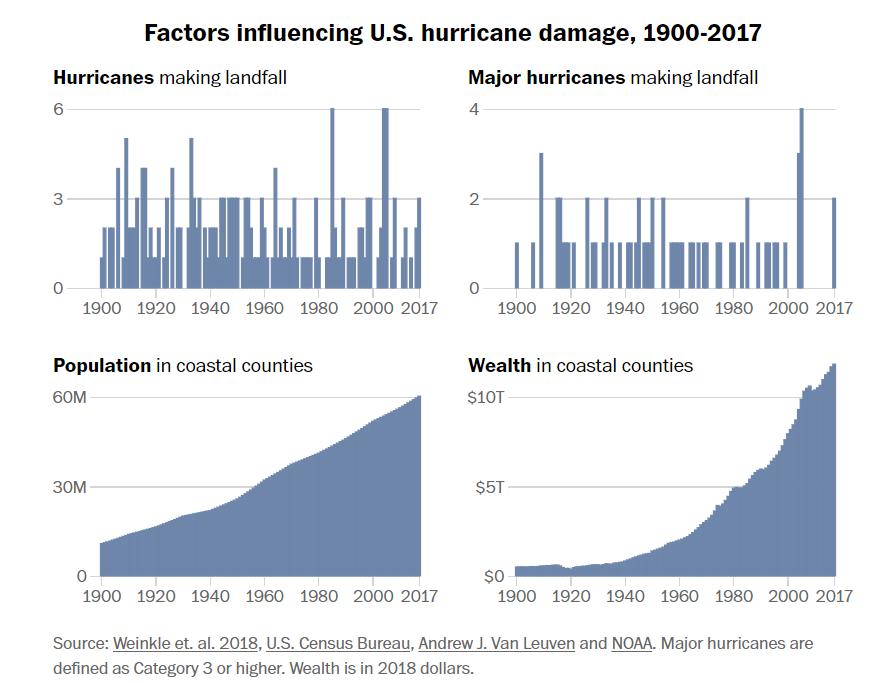

For the first time I can remember, a time series of mainland U.S. hurricane landfalls has been published by the major media as part of the Post’s explanation of our hurricane “normalization” research. The four panels below are a nice way to show trends underlying increasing disaster losses — I’m going to use this in future talks.

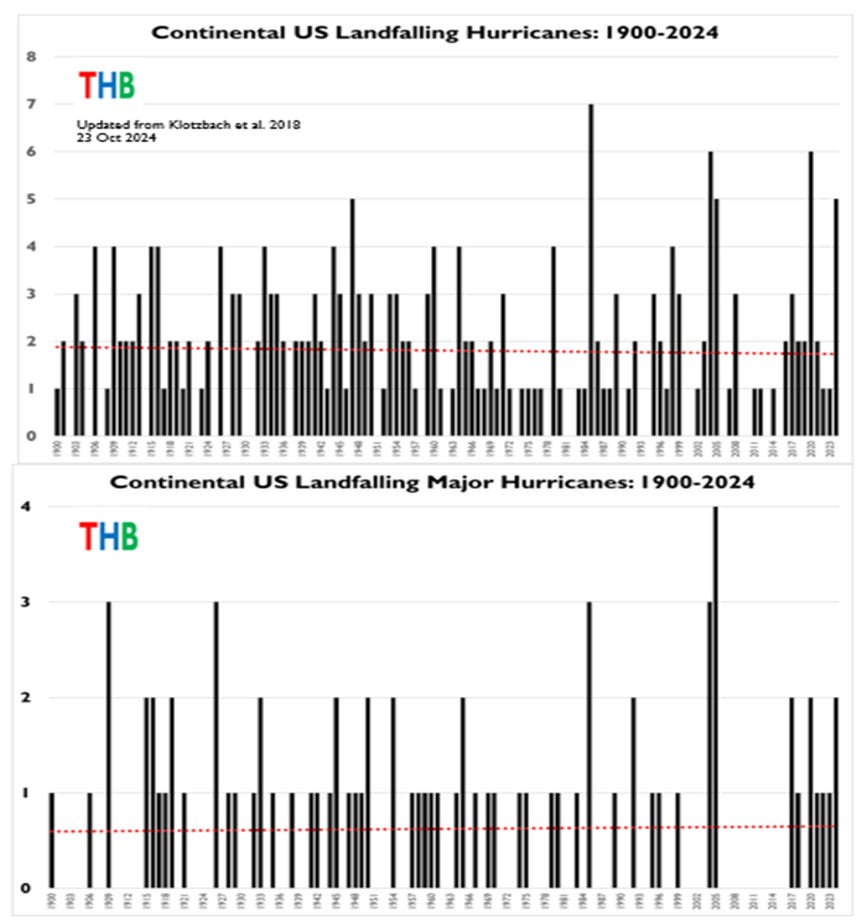

The hurricane landfall data shown above follows from our 2018 paper (which covered 1900-2017), and I’ve just updated hurricane and major hurricane landfall trends (through today) in the figure below.

The post quotes Laurens Bouwer — one of the world’s experts on disasters and climate change as well as a long-time IPCC contributor — on the current scientific consensus:

Yet the consensus among disaster researchers is that the rise in billion-dollar disasters, while alarming, is not so much an indicator of climate change as a reflection of societal growth and risky development.

“A lot of the things we see in the disaster losses are obscured because there’s an overwhelming signal of more people in risky places, growing populations worldwide, more infrastructure, more assets, higher values,” said [Laurens] Bouwer, the five-time IPCC lead author. “This is the main signal. And that’s where the science is at the moment.”

The Post also quotes me on scientific integrity, which I think is the larger story here:

“I always want to emphasize climate change is real. It’s serious,” Pielke said. “But that doesn’t mean anything goes when it comes to science.”

The article is richly reported and includes much more than I’ve discussed here.3 Before I send you to read the whole thing, I want to highlight some remarkable statements and admissions from NOAA, the Biden Administration, and U.S. National Climate Assessment (NCA) contributors:

In a statement to the Post, the White House doubles down on attribution: “Americans are already feeling the impacts of hurricanes, wildfires, floods, and drought. The science is clear: climate change is the existential threat of our time.”

NOAA also doubles down: “A lot of these extremes are really ramped up. If you want to act like nothing’s happening or it’s minimal, that’s just not the case . . .”

A NCA lead author (who happens to work for a climate activist organization) suggested that we should just assume attribution, no science needed: “I think then the burden might be to demonstrate that detected climate influence therefore has no effect whatsoever on the associated costs.”

Another NCA author stated that the BDD tabulation served promotional purposes, “to clearly communicate that climate change is a present-day problem here in the United States with significant impacts. We wanted to counter the common perception that climate change is a problem for the future and for someone else.”

Yet another NCA author explained that researchers felt pressure (from whom?) to connect climate changes to costs experienced today: “There’s been a lot of pressure on climate scientists to tell the story better.”

There is much, much more in the analysis and I encourage you to read the whole thing. This is climate reporting done right. Bravo Wash Post!

PS. I notice as I am writing this that Andy Revkin at SustainWhat is hosting a discission with Harry Stevens on the article. which will be available at Andy’s Substack and on YouTube.

You can also find the article at this archived link.

Some may recall that it was exactly this topic that led to the mobbing of Nate Silver and the witch hunt that forced me out of 538 back in 2014. Let’s see what has changed 10 years on.

My one criticism of the article is that the Post felt it necessary to politicize my work by associating it with Republicans and explaining who I’ll be voting for this election (Harris, duh). No other researcher in the article is treated the same way. The fact that my (and colleagues) research is found convincing by some Republicans (but not the Maga ones) should be welcomed — Many climate researchers spend a lot of time denigrating Republicans, how’s that been working out for building trust in climate science?

Harry Stevens' WP article is such a breath of fresh air. As I told Harry and Jessica Weinkle in our converastion this morning, this is what climate journalism should look like - starting with cllimate RISK and assessing how exposure and vulnerability (and vital assessment of past storm patterns on long time scales) are essential. https://revkin.substack.com/p/live-10-am-et-join-a-fresh-look-at

It’s about time!