Can democratic deliberation help the practice of democracy?

There are benefits, but its potential is limited

Citizen juries or assemblies are expert led and organized deliberations comprised of randomly selected citizens who are tasked with discussing a specific policy question or issue. Citizens meet over a period of days or weeks and are provided with access to expert testimony and relevant information to inform their deliberations. At the conclusion of the process, the leaders of the exercise issue a report or recommendation to policymakers or the public.

Here I discuss such deliberative exercises and find that while they have many potential benefits, their contributions to improved practices of democracy are limited.

The use of citizen assemblies has many champions as a means of addressing public policy challenges such as climate change, healthcare, and criminal justice reform. Proponents of such deliberative exercises argue that they offer several advantages over traditional forms of citizen engagement, such as public comment, public hearings or town hall meetings.

The notion of deliberative democracy is compelling. Citizen assemblies can offer a more open and inclusive way of engaging citizens in democratic processes. By using a random selection process, citizen juries seek to ensure that a diverse range of perspectives and experiences are represented in the deliberations. This can lead to a more nuanced and robust understanding of issues and help to foster greater trust and legitimacy in the policymaking process.

Citizen assemblies seek to facilitate closing the gap between policymakers and the public, as well as gaps between different publics within a society. Traditional forms of citizen engagement can devolve into shouting matches or political theater, with little substantive dialogue taking place. Public engagement exercises, by contrast, are designed to be more structured and focused, with clear rules and guidelines for how the deliberations should proceed. A formal structure seeks to foster a more constructive and productive dialogue among citizens and help to identify areas of common ground and shared values.

Despite these advantages, citizen assemblies also face several challenges that must be addressed for them to be successful. For instance, in a paper more than a decade ago Eva Lövbrand, Silke Beck and I argued that expert-led deliberative exercises could lead to a “democracy paradox” where expert-led deliberation might be just another form of undemocratic technocracy, with experts leading the public in the guise of deliberation and language of democracy, but which might be anything but.

I’ve reviewed some of the recent literature on citizen juries and below I my current (and still evolving) views on citizens assemblies as a form of deliberative democracy. The literature is vast, and I only scratch the surface here. I welcome your comments and perspectives. I have six points.

First, there are always questions about terminology – for me, these exercises might be best characterized as “deliberative mini-publics.” As a short-hand descriptor, I prefer “citizens assembly” over “deliberative polls,” “citizens jury” or other alternatives, as jury implies right/wrong rather than deliberation, and “poll” is readily misinterpreted, given its common usage. But it is important to recognize that there are different words used to describe similar concepts.

Second, one important (and large) obstacle in the way of success of any deliberative democracy effort is perceived legitimacy among policy makers and the public. Who legitimizes such an effort in the first place? Ideally a bipartisan group of legislators would request such an exercise with a commitment to consider its results, giving it immediate legitimacy. But bespoke deliberative exercises can be very costly – for instance government-legitimized deliberations in Ireland were $2-4 million each.

Third, coming up with a single proposed policy recommendation out of such deliberation is highly unlikely. However, developing novel options might be possible – honest brokering -- and indeed could allow new ideas and options to enter gridlocked discussions of these key issues. Any such exercise should be outsourced to those with a track record of expertise and experience in performing such public engagement.

It is important to acknowledge that almost all deliberative democracy exercises fail to have direct impacts on policy (e.g., via subsequent referenda or legislation), but may have other value, such as developing more nuanced understandings of public opinion or fostering the identification of novel policy options.

Any such exercise is implemented either to augment democratic processes or to address shortfalls in formal democratic mechanisms. In either case legitimacy is paramount. Otherwise the risk is conducting an academic exercise, which may be interesting but of no practical importance. Securing legitimacy is step one, in my view.

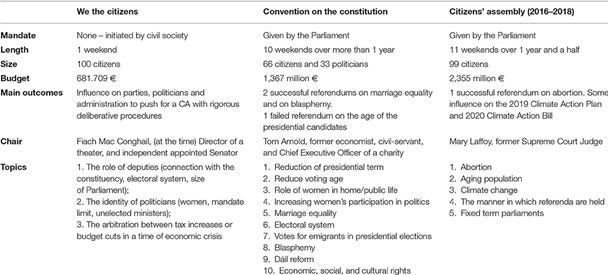

Fourth, does the apparent success of citizens assemblies in Ireland suggest a transferrable model? Well, yes and no. The Irish model is one of very few where citizens assembly results were legitimized by subsequent national referenda. Ireland held 4 such assemblies -- on politicians, the constitution, abortion, climate, with the first three having direct policy impacts.

See a summary below. Note the budgets, which run into the millions of dollars per engagement.

A key factor in the Irish examples is that three of the assemblies were mandated by the Irish parliament. So they had formal legitimacy from the start. That said, similar approaches to deliberative democracy in Iceland and British Columbia resulted in referenda that were defeated. Many other countries and jurisdictions have implemented various forms of deliberative engagement. See especially the notable research of the Consortium for Science, Policy and Outcomes at Arizona State University.

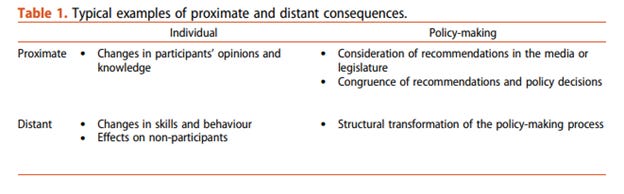

Fifth, there are worthwhile outcomes beyond policy change. Consider the multiple dimensions of outputs are highlighted in the table below. Success of any public engagement exercise will thus be a function of the intended goals of the exercise. Keeping expectations realistic and in check is key. There is no doubt academic value to such exercises, but that may not translate to policy siugnificance.

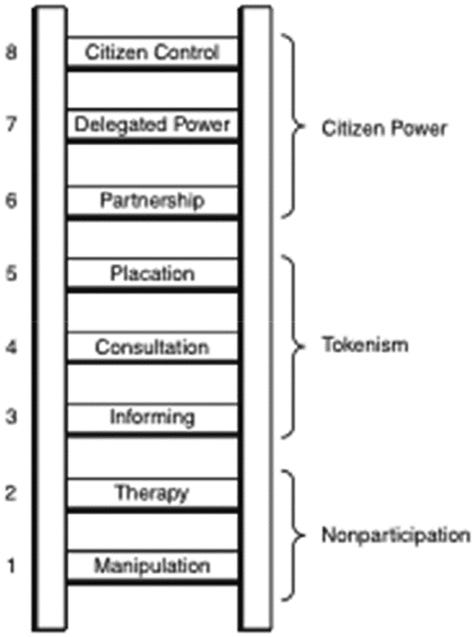

I find Arnstein’s (1969) “ladder” of citizen participation to offer a useful vocabulary for discussing the ends and means of such exercises. Those advocating for such deliberative engagement should be very explicit about their goals and objectives.

Sixth, there are a lot of choices to be made in the design of participatory democracy initiatives. Some of these are highlighted by Bobbio (2019) in the table below. It is important to have clarity on the ends and means of any such exercise. This obviously interconnects with issues of legitimacy, and ultimately what the organizers of deliberative efforts think “democracy” is in the first place.

What makes for an effective exercise in deliberative democracy? Perceived legitimacy, perceived fairness, balanced participation and the specific details of the participatory setting (e.g., task, time, roles, rules, facilitating style). Just as with all types of democracy, deliberative democracy is more art than science.

Here are the tentative and preliminary conclusions I’ve reached so far after reviewing literature on citizen assemblies as a form of deliberative democracy:

Citizen engagement exercises are difficult to do;

Any such exercise should be outsourced to those with expertise and experience (there are not many, but some, mainly in university settings);

They can be costly;

They are usually time intensive (can span years);

There is a risk of failure in the form of outcomes that are highly perishable, not of particular use or mainly of academic interest;

The track record of such exercises in actual practice is mixed;

Even so, such exercises done well are worth doing, for the simple reason that we learn more about each other, our politics and we might even open up policy discourse to new and innovative ideas.

Some further reading

Arnstein, S. R. (1969). A ladder of citizen participation. Journal of the American Institute of Planners, 35(4), 216-224.

Bobbio, L. (2019). Designing effective public participation. Policy and Society, 38(1), 41-57.

Coote, A., & Lenaghan, J. (1997). Citizens' juries: theory into practice. Institute for Public Policy Research.

Courant, D. (2021). Citizens' Assemblies for Referendums and Constitutional Reforms: Is There an “Irish Model” for Deliberative Democracy?. Frontiers in Political Science, 14.

Elstub, S., & Escobar, O. (Eds.). (2019). Handbook of democratic innovation and governance. Edward Elgar Publishing.

Jacquet, V., & van der Does, R. (2021). The consequences of deliberative minipublics: Systematic overview, conceptual gaps, and new directions. Representation, 57(1), 131-141.

Lövbrand, E., Pielke Jr, R., & Beck, S. (2011). A democracy paradox in studies of science and technology. Science, Technology, & Human Values, 36(4), 474-496.

Mannarini, T., & Fedi, A. (2018). Using quali-quantitative indicators for assessing the quality of citizen participation: A study on three citizen juries. Social Indicators Research, 139(2), 473-490.

Thanks to Environmental Progress for a grant to perform this review.

I don’t get it. Why do we elect parlaments then?

In principle, this could result in better policies. But in our unprincipled world, the Public expects almost instant action / gratification - DD is too slow. Those who want to drive action are either on the Left or Right ideologically, while most of us are in the muddle-through Middle. DD generally should yield recommendations reflecting the majority Middle, which neither of the ideologues are likely to accept. And we have a mainstream media which is trying to drive us all toward a single narrative.

Sadly, DD is not the cure for what ails us. If we want better policies, we need better politicians. Ones who have the courage to consider all the facts, and not just cherry pick those that fit their narratives. Ones who will strive for real cures for our ills, and not just feel-good placebos. Ones who will recognize that our society and country are too complex for one-size-fits all solutions for all of our problems.

In short, we need politicians who have internalized the words of Bastiat (I've substituted politician for economist):

"There is only one difference between a bad [economist] politician and a good one: the bad [economist] politician confines himself to the visible effect; the good [economist] politician takes into account both the effect that is seen and those effects that must be foreseen.

Yet this difference is tremendous; for it always happens that when the immediate consequence is favorable, the later consequences are disastrous, and vice versa. It follows that the bad [economist] politician pursues a small present good that will be followed by a great evil to come, while the good [economist] politician pursues a great good to come, at the risk of a small present evil."