U.S. National Security Strategy and Climate Change

The Biden Administration fails to take climate or energy seriously

Last month, President Biden released the administration’s 2022 U.S. National Security Strategy (NSS), the highest-level articulation of values and aims of the United States national security. The U.S. National War College offers a valuable primer on the NSS and describes its origins (in fact, it is so good that I will use this document in future policy classes):

In 1986, the Goldwater-Nichols Department of Defense (DOD) Reorganization Act established a more deliberate, structured, and formalized approach to developing an overarching national security strategy. The Goldwater-Nichols Act directs the President to submit an annual report to Congress that sets forth the national security strategy of the United States; details the country’s vital worldwide national security interests, goals, and objectives; and outlines the proposed short- and long-term uses of national power. President Ronald Reagan submitted the first of these reports, titled National Security Strategy of the United States, in 1987.

In this post I discuss one aspect of the 2022 NSS — climate change.

Here are the number of mentions in the NSS of some key words related to U.S. national security. You can see that climate ranks near the top.

economy/economic = 111

democracy/democratic = 81

technology/technologies/technological = 78

climate = 63

China, PRC, PRC’s = 55

energy = 50

Europe/European = 34

Ukraine = 33

Russia = 32

rights = 31

nuclear = 23

authoritarian/s/ism = 8

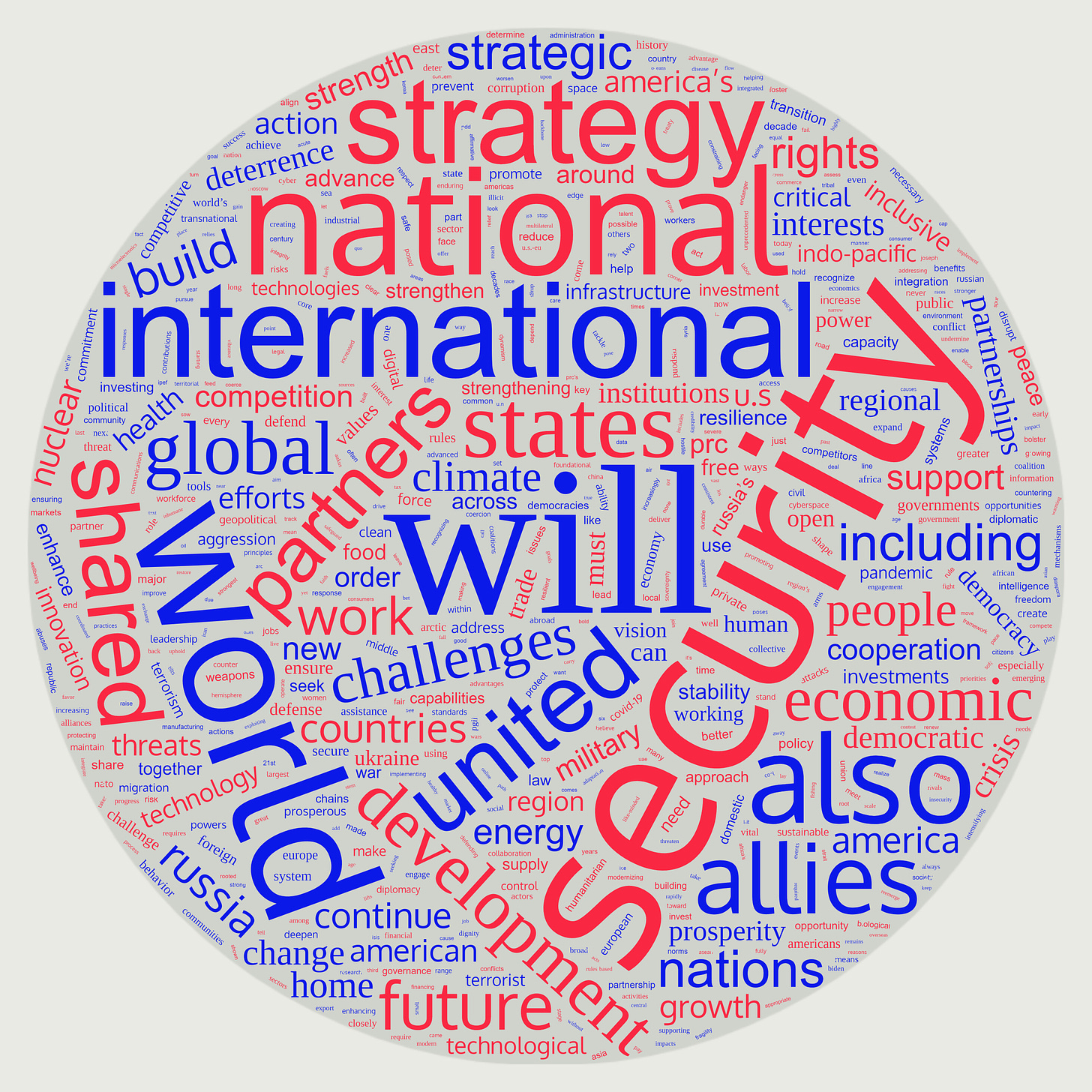

Below, you can see a complete word cloud of the entire NSS. The larger the font, the great number of appearances in the document. You can find “climate” just above the big “will” near the center.

Climate change is presented in the Strategy as the single greatest threat facing the world, and is characterized as potentially threatening the existence of all nations:

Of all of the shared problems we face, climate change is the greatest and potentially existential for all nations. Without immediate global action during this crucial decade, global temperatures will cross the critical warming threshold of 1.5 degrees Celsius after which scientists have warned some of the most catastrophic climate impacts will be irreversible.

The Strategy portrays climate change is dystopian terms:

Climate effects and humanitarian emergencies will only worsen in the years ahead—from more powerful wildfires and hurricanes in the United States to flooding in Europe, rising sea levels in Oceania, water scarcity in the Middle East, melting ice in the Arctic, and drought and deadly temperatures in sub-Saharan Africa. Tensions will further intensify as countries compete for resources and energy advantage—increasing humanitarian need, food insecurity and health threats, as well as the potential for instability, conflict, and mass migration. The necessity to protect forests globally, electrify the transportation sector, redirect financial flows and create an energy revolution to head off the climate crisis is reinforced by the geopolitical imperative to reduce our collective dependence on states like Russia that seek to weaponize energy for coercion.

However, despite this apocalyptic framing, climate largely plays a window-dressing role in the report, with mention of “climate” often tacked on sentences as if to underscore its importance, but with little in the way of actual strategic analysis.

For instance, most of the 63 mentions are similar to the following examples, emphases added:

“Combatting the climate crisis, bolstering our energy security, and hastening the clean energy transition is integral to our industrial strategy, economic growth, and security.”

“NATO has responded with unity and strength to deter further Russian aggression in Europe, even as NATO also adopted a broad new agenda at the 2022 Madrid Summit to address systemic challenges from the PRC and other security risks from cyber to climate”

“The Indo-Pacific is the epicenter of the climate crisis but is also essential

to climate solutions, and our shared responses to the climate crisis are a political imperative and an economic opportunity.”

Climate is frequently mentioned, but there is little to no accompanying analysis or strategic discussion. One might expect a bit more depth on an existential threat that threatens all nations on the planet.

The section of the NSS devoted specifically to climate and energy reads less like a discussion of U.S. national security and more like a generic stump speech on the Administration’s climate policy ambitions:

Global action begins at home, where we are making unprecedented generational investments in the clean energy transition through the IRA, simultaneously creating millions of good paying jobs and strengthening American industries. We are enhancing Federal, state, and local preparedness against and resilience to growing extreme weather threats, and we’re integrating climate change into our national security planning and policies. This domestic work is key to our international credibility, and to getting other countries to up their own ambition and action.

The United States is galvanizing the world and incentivizing further action. Building on the Leaders’ Summit on Climate, Major Economies Forum, and Paris Agreement process, we are helping countries meet and strengthen their nationally determined contributions, reduce emissions, tackle methane and other super pollutants, promote carbon dioxide removals, adapt to the most severe impacts of climate change, and end deforestation over the next decade. We’re also using our economic heft to drive decarbonization. Our steel agreement with the EU, the first-ever arrangement on steel and aluminum to address both carbon intensity and global overcapacity, is a model for future climate-focused trade mechanisms. And we are ending public finance for unabated coal power, and mobilizing financing to speed investments in adaptation and the energy transition.

The report alludes to strategic concerns when discussing Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, but even there the discussion remains thin:

Events like Russia’s war of aggression against Ukraine have made clear the urgent need to accelerate the transition away from fossil fuels. We know that long-term energy security depends on clean energy. . . we will drive concrete action to achieve an energy secure future.

It is not clear how long-term the long term is here, but over the past few days President Biden implored and threatened oil and gas companies with tax sanctions if they do not work quickly to produce more fossil fuels and to lower the market prices of energy for consumers. Surely any strategic analysis would recognize the importance of short- versus long-term energy policy goals and how issues like security of domestic supply, international destabilization caused by higher energy and food prices (due to short-term supply/demand mismatches of fossil fuels) and market uncertainty might intersect with U.S. national security concerns.

You won’t find much of that here.

In short, if I am a leader of the U.S. defense or intelligence communities, I would feel a bit befuddled by what is to be done (if anything) strategically and operationally based on the NSS discussions of climate change. As a policy scholar with lots of expertise in climate policy and policy making more generally, but very little in national security strategy if I were to have an audience with national security leaders, here are the three things I would tell them.

First, climate matters. It is not just climate change, but documented, well-established climate variability on all timescales, with notable modes of variability that include ENSO, IOD, PDO, NAM, NAO, SAM and more. These modes and associated teleconnections result in climate anomalies around the world, sometimes with a degree of predictability, but often not. If the previous sentences sound like gobbledygook to national security decision makers, then that is a problem, as it is through variability (in the context of change) that weather and climate impacts of strategic importance will manifest themselves. Focus on climate — it matters for national security.

Second, beware the political attractiveness for politicians, the media and various advocates in and out of government of using national security as a way to promote energy and climate policy objectives that may have little connection with near-term national security. There is no doubt that the U.S. Department of Defense can be a huge player in accelerating the decarbonization of the U.S. economy. However, it is one thing to employ DoD as a means for achieving climate policy objectives and quite another to reorient DoD strategy to focus on those climate policy objectives as if they were national security goals. Mission creep is a risk, so too is a loss of focus on national security.

Third, climate scenarios, once again. The U.S. national security community has not been immune from the totalizing presence of implausible climate scenarios, notably our old friend RCP8.5. For instance current guidance to military decision makers for short- and long-term planning for sea level rise focuses on RCP8.5, based on scenario analyses now more thana decade old. The national security literature is rife with RCP8.5. As I have documented, there may be good reasons to use implausibly extreme scenarios in exploratory research or for attracting clicks, but they are no basis for national security planning in the real world. The national security community needs to develop more effective ways to ensure that it is using the best available science. It’s a problem if those in U.S. national security are using climate scenarios without a deep appreciation of what they are (and are not), their proper uses, and when they are obsolete.

Overall, the Biden Administration’s discussion of climate (and energy) in the 2022 National Security Strategy left me disappointed.

Climate is far too important to be reduced to a largely meaningless appendage to multipart listicles: “we face risks from X, Y and climate change.” In public and policy discourse, the phrase “climate change” has largely lost its scientific meaning and today variously refers to greenhouse gas emissions or the societal effects of everything that is related to weather or climate. This sort of imprecision is not the stuff of effective security strategy. Climate variability in the context of change, and associated weather events, will remain significant for U.S. national security. This topic deserves more strategic attention.

Finally, energy policy is far too important to be reduced to simplistic talking points and exhortations about the need to quickly eliminate fossil fuels. In the aftermath of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, the world did not see an immediate rush to abandon fossil fuels. In fact, the opposite occurred, with nations scrambling to secure fossil fuel resources — including oil, coal and natural gas.

An effective national security strategy will recognize that fossil fuels will continue to dominate the world’s energy supply for the near-term — at least — even as the world rightly seeks to pivot to a fossil-free future. How to achieve those seemingly opposed objectives while simultaneously securing U.S. national security would be a great topic for some strategic thinking.

Roger, an excellent piece! Words have consequence both from the right and the left. The unrelenting chorus of disaster from climate activists can change positions and investment in defense, energy and agriculture. I know you saw Tom Friedman's interview on CNN where he said the climate activists in the Biden administration have basically said oil companies are dinosaurs and should go off quietly and die. This has undercut both their willingness and their investor's appetite to make long term investments in new oil production. As Friedman says this has contributed to our inability to deal with the current Ukraine / Russia energy crisis and current inflation. The current water problems in the Colorado River basin which have been loudly tied to climate change are not linked since snowpack in the upper basin shows no long-term trend and climate change models themselves show increasing precipitation in most of the basin. But this may set into place expensive fixes as the price of climate change such as desalination and paying farmers not to use water. Since 80% of the water in the basin (and also much of the rest of the West) is used for agriculture the real solution to western water problems is to move some crops (cotton, rice, hay, corn) back to the east where they were in the last century. This would preserve agricultural output and national food/fiber security as opposed to paying farmers ten times the amount they pay the BurRec for water now for doing nothing.

Sadly, stump speech rhetoric substitutes for critical thinking in many USG documents. How does resilience/independence on energy, minerals, etc. fit in the document?