How extreme was the weather in the United States in 2022?

Of course the year is not over, and more extreme weather will yet occur, but most of the year has passed and it is not too early to take a look back at how 2022 looks in historical context. I wanted to get this out before NOAA blasts out its “billion-dollar disaster” press kit, along with the implication that damage from disasters tells us something about extreme weather.

If you want to understand trends in extreme weather, look at weather data, not economic data.

In a few words, extreme weather in 2022 in the U.S. has been — well, pretty normal. Some extreme weather phenomena occurred at a rate or intensity greater than historical averages, but many occurred less. There have been and there will again be many years with far more extreme weather than we’ve seen in 2022.

In this post I share for a range of extreme weather phenomena 10 graphs and links to original data sources for those who’d like to dive deeper. For those who want a summary first, here is what I document below:

Extreme temperatures — higher than historical average

Drought — above average this century, not as pronounced longer-term

Tropical Cyclones — average to below average

Tornadoes — Below average (since 2005)

Hail — Below average (since 2005)

Strong winds — above average (since 2005)

Fire — Average (since 2000)

Flooding and Extreme Precipitation — Data not yet available, but appears average

Let’s jump right into the data.

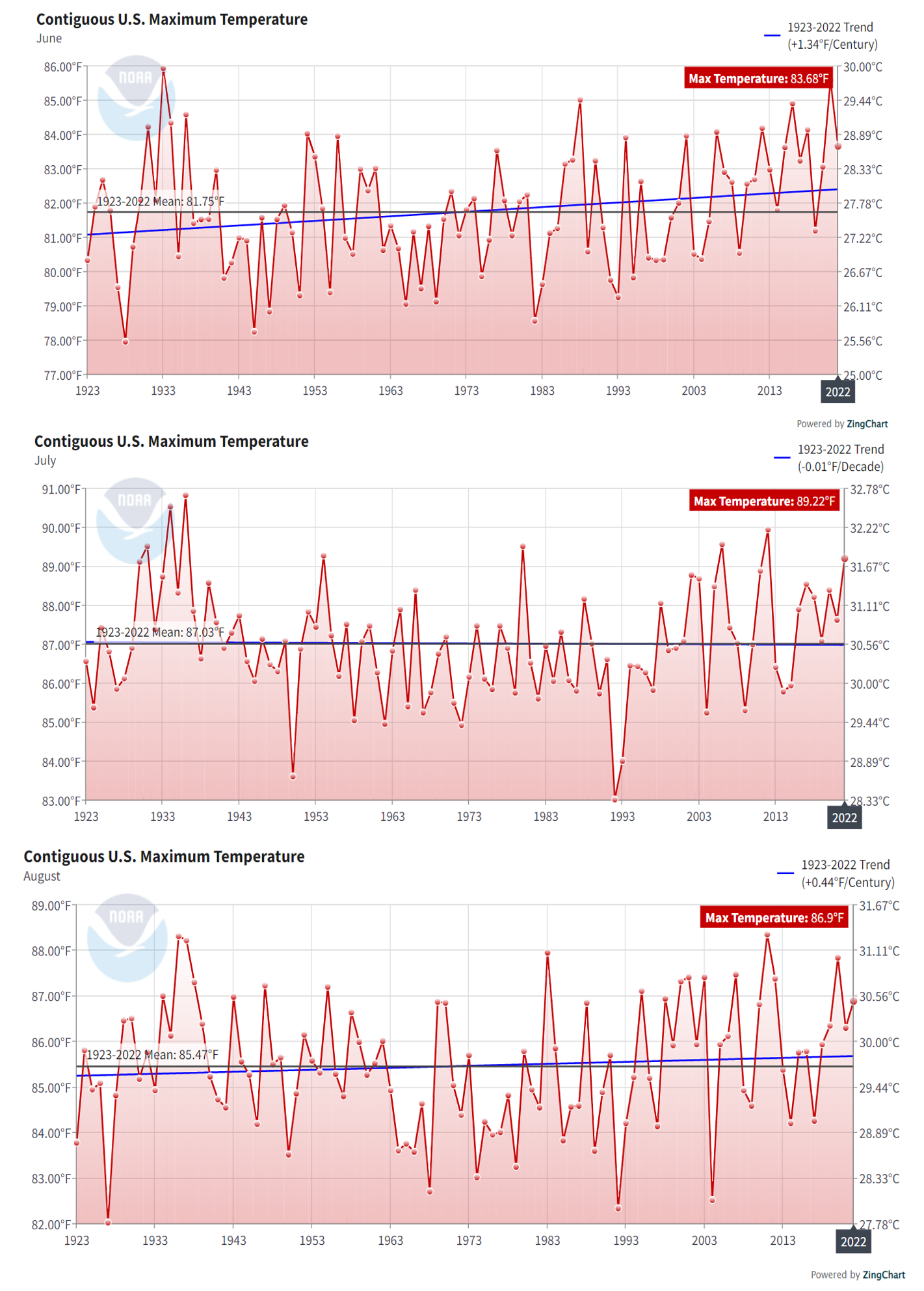

Extreme temperatures

The graphs below (via NOAA) show U.S. maximum temperature trends for the past 100 years for the continuous U.S. states for June, July and August, arranged from top to bottom. In each month of the summer of 2022, U.S. maximum temperatures were higher than the long-term average.

June is ranked 14th of the past 100 years, July at 7th and and August at 17th.

You can also see that there is a slight upwards trends for June, no trend for July and a small trend for August. Of course, one can arrive at different trends by starting the analysis at different points. In general, trends will be much smaller if the period analyzed includes the 1930s — which were very extreme — and much larger of they start in the relatively cooler 1960s.

Drought

The year to date has seen a somewhat higher level of drought as compared to the post-2000 period, which you can see on the far right in the graph below.

The plot below integrates severity and areal extent and you can see that 2022 sits near the upper end of drought levels observed this century, but one would find it difficult to identify a strong trend over this short period.

The graph below shows a much longer-term perspective for the continuous U.S. over the past 100 years. Under this metric (the PSDI) drought across the lower-48 has actually decreased a bit on that time scale, but the trend is small. Once again the 1930s heavily influence any longer-term trend analysis.

Another perspective can be found in the graph below, which shows the proportion of the U.S. that is abnormally dry or abnormally wet.

Again, there is little hint of strong trends in the data, but there is some reason to believe that 2022 saw less areas of extreme wetness than observed earlier this century and throughout the longer-term record.

Tropical Cyclones

In an earlier post I documented how the 2022 North Atlantic hurricane season underperformed compared to seasonal forecasts published earlier this year. You can see that in the graph of cumulative ACE below (via Colorado State University). ACE refers to Accumulated Cyclone Energy and integrates intensity and frequency of storm activity.

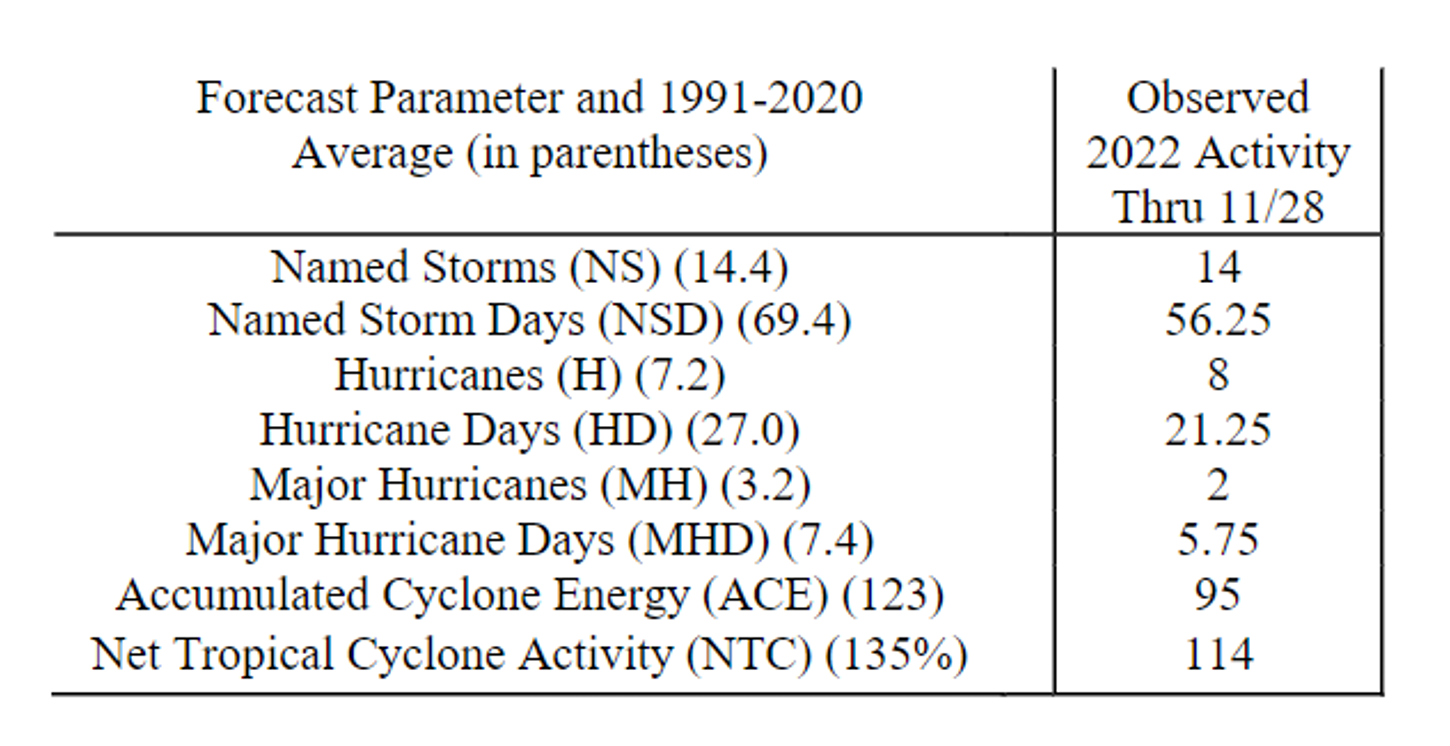

Most metrics of North Atlantic hurricane activity were close to average or below average, as you you can see in the table below (via Colorado State University).

However, the number of continental U.S. landfalls was at the long-term average for both all hurricanes (2 vs. an average of 1.8, since 1900) and major hurricanes (1 vs an average of 0.6). A few days ago, I looked at the hurricane damage of 2022 (mainly from Hurricane Ian) in longer-term context.

Tornadoes

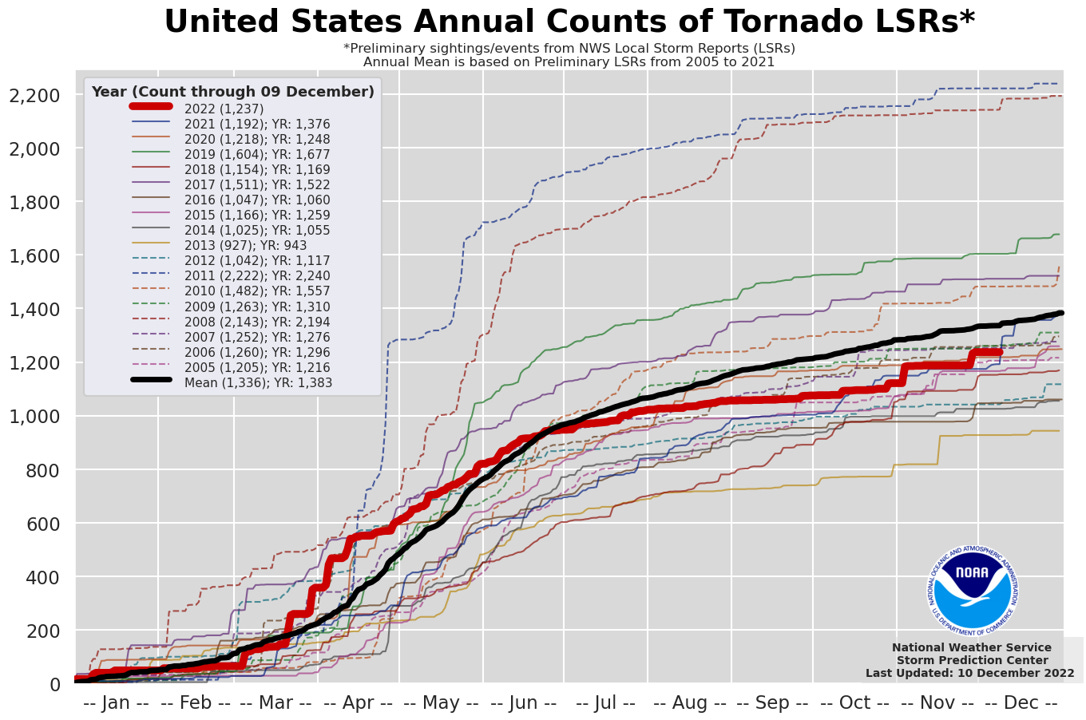

One interesting fact about extreme weather in the U.S. is that much of the past decade has seen below average tornado activity. You can see that in the figure below.

If you take a close look at the table in the upper-left of the graph, you’ll see that 10 of the past 11 years have seen below average tornado activity (since 2005), with 2022 (in red) continuing that trend. The last really big tornado year was 2011.

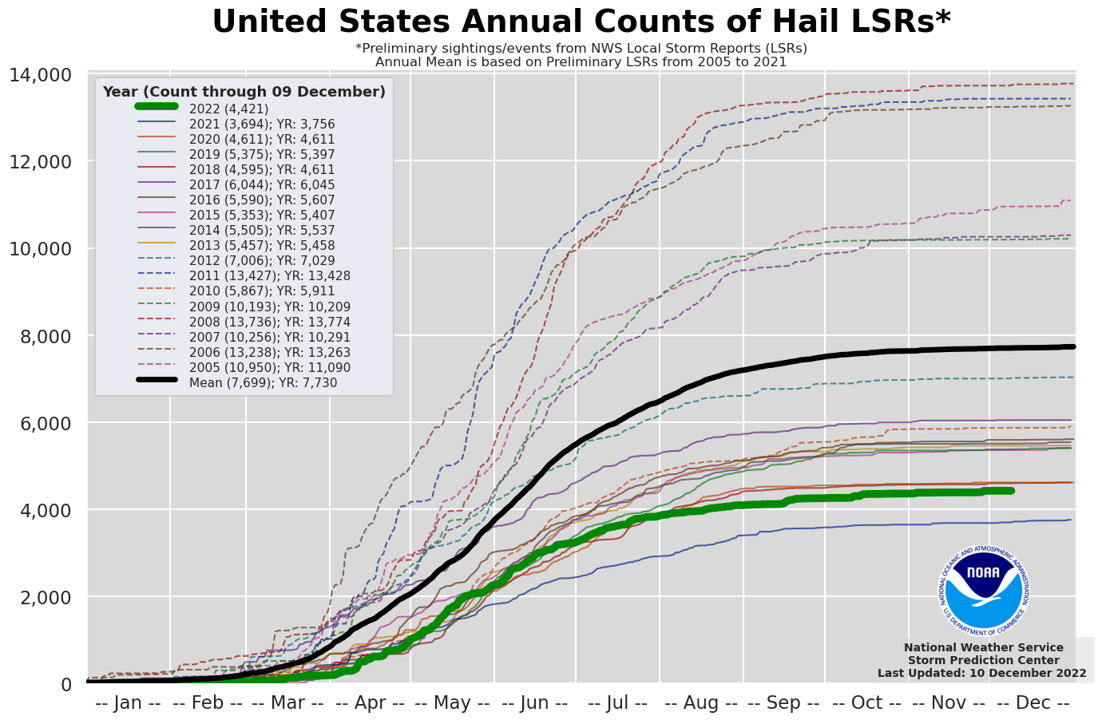

Hail

Another little appreciated extreme weather fact has been the relative lack of hail. Each of the past 11 years has been below average (since 2005). In fact, 2022 has the least hail since 2005, undercut only by 2021.

That tornadoes and hail would each show similar trends makes sense, as both are the result of convective storm activity.

Strong winds

Counter to the low levels of tornadoes and hail, 2022 saw slightly higher than average (since 2005) levels of extreme winds, as you can see in the figure below. For strong winds, 6 of the past 10 years have been below average.

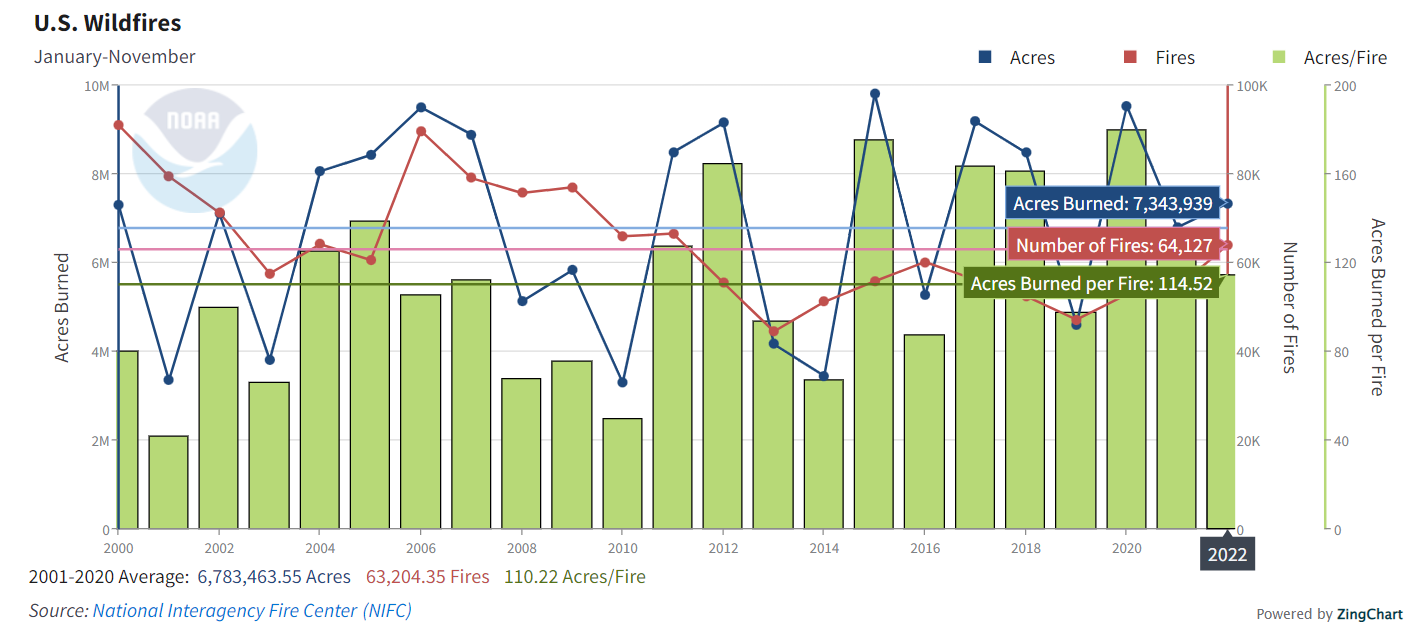

Fire

For fire, 2022 was just about average since 2000 in terms of the number of fires, acres burned and acres per fire.

Flooding and Extreme Precipitation

Data that would allow an evaluation of 2022 is not available yet. Based on the various data that might be related, such as wet days and spatial extent of drought, my working hypothesis that each were likely around normal. I’ll update when data become available

Your comments, questions and suggestions are welcomed!

Thank you for your above helpful summary. Would also like to see correlation to CO2 levels as your time and priorities permit.

I am no expert but I am puzzled about temperatures because it would be interesting to compare various sources, e.g. satellite measurements, and also the urbanization impact. As far as I know the NOAA measurement stations might have been impacted and therefore might overestimate temperature. Just asking....