More than 5,000 people have died in flooding centered on Derna, Libya, following heavy rains that collapsed at least two dams upstream from the city. The AP reports:

Mediterranean storm Daniel caused deadly flooding in many towns of eastern Libya on Sunday, but the worst-hit was Derna. Two dams outside in the mountains above the city collapsed, sending floodwaters washing down the Wadi Derna river and through the city center, sweeping away entire city blocks. . . The startling devastation pointed to the storm’s intensity, but also Libya’s vulnerability. The country is divided by rival governments, one in the east, the other in the west, and the result has been neglect of infrastructure in many areas.

Derna’s vulnerability to flooding was well known, having experienced major floods in 1942, 1959, 1968 and 1986. The threat posed by poorly maintained dams upstream of Derna was the subject of a research article published last November by Abdelwanees A. R. Ashoor, in the Civil Engineering Department of Omar Al-Mukhtar University in Albeida, Libya.

Ashoor warned:

The current situation in the Wadi Derna basin requires officials to take action Immediate measures to carry out periodic maintenance of existing dams. A huge flood, the result will be catastrophic . . .

Ashoor 2022 (via Google Translate)

Today I review what the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) and the peer-reviewed literature tell us about longer-term trends in flooding on the African continent.

Let’s start with a review of what the IPCC says about flood trends globally:

“There is low confidence about peak flow trends over past decades on the global scale . . .”

“a low confidence in general statements to attribute changes in flood events to anthropogenic climate change . . .”

“Attributing changes in heavy precipitation to anthropogenic activities cannot be readily translated to attributing changes in floods to human activities . . .”

“there is low confidence about human influence on the changes in high river flows on the global scale . . .”

For floods in Africa specifically, the IPCC says:

On a continental scale, a decrease seems to dominate in Africa (Tramblay et al. 2020)

Let’s next look at some details of the peer-reviewed literature that informed the IPCC’s conclusions on flooding on the African continent. One recent study — cited by the IPCC above — found an overall decrease in flooding at the continental scale from 1950 to 2010, but with considerable spatial and temporal variations:

[T]here are statistically significant decreasing trends in annual maximum discharge at 214 out of 884 stations during 1950–2010, with increasing trends at only 60 stations. Overall, the largest changes are clustered in western and southern Africa. Based on these results, we would conclude that flooding in Africa has been decreasing since the 1950s, consistent with the results obtained by previous studies (Do et al 2017, Wasko and Sharma 2017).

A lack of consistent, reliable data presents significant challenges to the identification of trends and variability in extreme precipitation and streamflow across Africa. River discharge data was actually better collected in the 1970s, and has since seriously degraded.

As in many places around the world, the relationship of extreme precipitation and flooding is not straightforward. A 2021 study of the “drivers” of flooding in Africa found that antecedent soil moisture conditions were more important than extreme precipitation:

There is a strong seasonal cycle of floods in the different African regions: Floods occur mostly during late fall and winter in North and South Africa, and in the summer in Western and central Africa. This seasonal behavior is related to annual maximum rainfall and soil moisture patterns, but the seasonality of floods is more strongly related to soil moisture than to annual maximum rainfall. Indeed, the correlation between the mean day of occurrence of annual maximum flood is more strongly tied to annual maximum soil moisture than to 5-day or 1-day rainfall maxima.

They conclude:

Overall, annual maximum daily rainfall is only a weak predictor of annual floods, therefore inferring variability in flood risk from annual maximum rainfall alone would not be very relevant. It is worth mentioning that the links to flood seasonality and their drivers identified here are very similar to the results obtained in very different climatic zones, such as North America, Europe or Australia, indicating that antecedent soil moisture plays a key role globally across multiple regions.

This complexity is one reason that the IPCC AR6 was very clear in warning that increases in heavy precipitation should not be taken to imply a corresponding increase in flooding — a warning routinely ignored in major media coverage of climate.

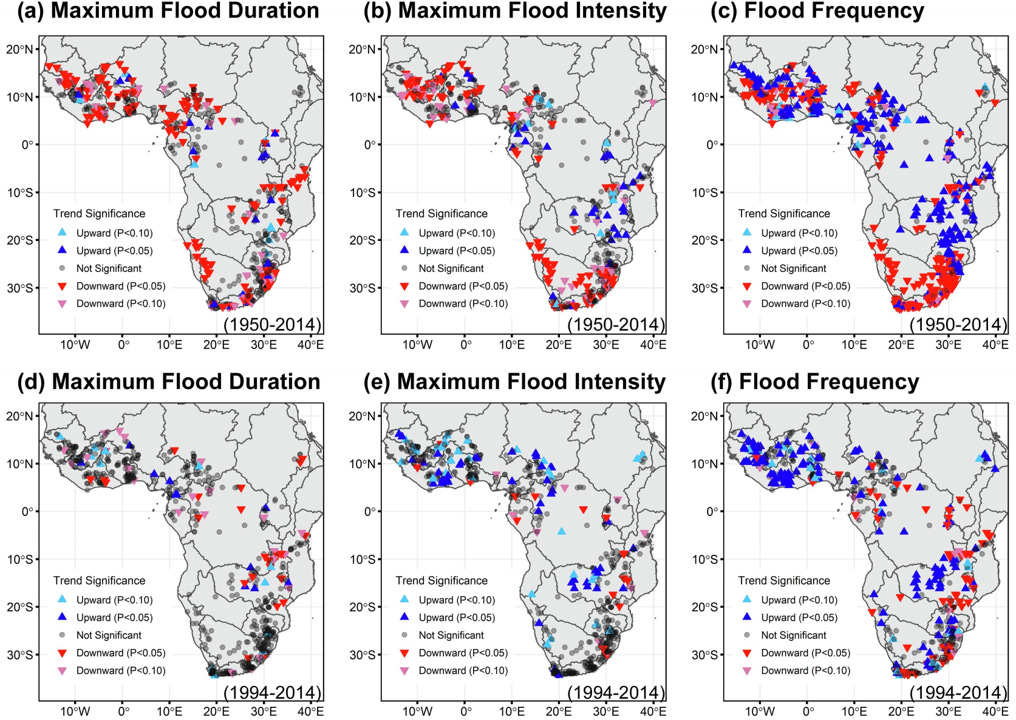

Looking at sub-Saharan Africa (SSA), Ekolu and colleagues found considerable variability in floods (and drought) but no long-term, secular trends from 1950 to 2014:

[B]y considering different starting and ending years, we note that trends computed for each of the flood and drought characteristics in the major hydrological basins in SSA are highly variable both in space and time. Such strong spatio-temporal variability in SSA catchments makes it difficult to discuss the presence of significant long-term trends in all flood and drought characteristics between 1950 and 2014. Most SSA catchments show alternating periods of increasing and decreasing trends in flood and drought duration, intensity, and frequency (Fig. 7, Fig. 8, Fig. 9), suggesting that significant decadal to multidecadal variations could be present in all flood and drought characteristics. Overall, such variations show similar directional and temporal patterns (or timing) in either flood or drought characteristics for most of the catchments, but these changes are generally in opposite directions between the floods and droughts. More importantly, however, such variations are aperiodic (i.e., magnitude changes over time), and this can substantially affect trend detection analysis.

When I read such studies I cannot help but think that the importance of climate variability has been diminished by the totalizing emphasis on climate change. In the short-term, climate variability matters much more than climate change (human-caused or otherwise) for the climate impacts that people actually experience.

With respect to changes in extreme precipitation, The IPCC expresses only low confidence in any increasing trend on the African continent, and that conclusion holds only for two regions in South Africa. A post-AR6 study looked more broadly at trends in extreme precipitation across Africa since 1981, finding considerable spatial and temporal variability, but no continent-wide secular trends:

Roughly 20% of the continent experienced significant trends (Mann-Kendall, 0.05) in annual maxima, with both positive (Sahel, Kenya and Tanzania, coastal regions of the Gulf of Guinea, coastal regions of the Middle East) and negative (Middle East, inland areas of west Africa, South Africa and Namibia, and a vast region in central Africa extending from Sudan to Angola) changes.

Bottom line:

Africa, like many places around the world, has profound vulnerabilities to flooding

Data on exposure, vulnerability, flooding and precipitation is available, but could be improved

Flooding is highly variable across the African continent and across time

Neither detection nor attribution of changes in flooding has been achieved (IPCC)

The IPCC AR6 suggests that flooding across Africa has decreased

Whether flooding has decreased or not, more attention to reducing vulnerabilities will always make sense

Thanks for reading! Please share, like, and broadcast on your favorite social media. I welcome you comments and suggestions. If you are not yet a subscriber, I invite you to join the THB community at whatever level makes sense for you. If you are already a subscriber, please consider an upgrade to support independent analyses like this that you will not find anywhere else.

Thanks for the great information. One typo, I think: Should the second "but" in this sentence be "by"?

"When I read such studies I cannot help but think that the importance of climate variability has been diminished but the totalizing emphasis on climate change."

I am not sure whether Roger appreciates the attention he got on "Real Clear Investigations"? They kinda lumped him in with CO2 deniers, which he is adamantly not.