The Original Pandemic Lab Leak Debate

The H1N1 virus of the 1918 influenza pandemic abruptly disappeared from human populations in the 1950s, only to re-emerge in 1977, very likely a result of human error

In 1977 public health officials detected a flu strain in China and Russia that mainly affected young people. The so-called Russian or Red flu spread rapidly and was ultimately responsible for about 700,000 deaths worldwide. Research into the flu provided strong hints that it may have not had a natural origin. If so, the 1977 outbreak would have been the world’s first pandemic caused by human error in research and public health.

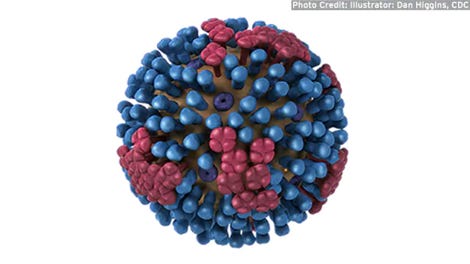

The 1977 pandemic was caused by one of three subtypes of the influenza A virus with pandemic potential — called H1N1 (the others are H2N2 and H3N2). The H1N1 virus is also called the swine flu, because it also is found in pigs. Soon after the flu outbreaks in Russia and China were detected, researchers discovered that it was swine flu causing the illnesses, immediately raising questions.

The H1N1 swine flu virus was responsible for the 1918 influenza pandemic which killed as many as 50 million people worldwide. Following the pandemic, the virus and its descendants continued to circulate in the human population until it “abruptly disappeared from humans in 1957 and was replaced by a new reassortant virus that combined genes from the H1N1 strain and an avian virus.”

In 1978, research led by Peter Palese of the City University of New York demonstrated that the newly emergent H1N1 pandemic virus was “very closely related” to “two H1N1 viruses isolated in 1950.” Vincent Racaniello, today a professor at Columbia University, was a PhD student in Palese’s lab in 1978 and in 2009, he described the significance of the 1977 finding of the close similarity of the two viruses:

Why were the viral genomes of the 1977 H1N1 isolate and the 1950 virus so similar? If the H1N1 viruses had been replicating in an animal host for 27 years, far more genetic differences would have been identified. . . The suggestion is clear: the virus was frozen in a laboratory freezer since 1950, and was released, either by intent or accident, in 1977. This possibility has been denied by Chinese and Russian scientists, but remains to this day the only scientifically plausible explanation.

Other researchers concurred: “The 1977 reemergence of the H1N1 subtype is an exceptional case: this virus from 1950 almost certainly escaped back into nature from frozen storage.”

The close similarity between the 1977 and 1950 viruses contradicted scientific understandings of how viruses evolve over time, as explained in 2006 by Edwin Kilbourne, of the New York Medical College: “Where had the virus been that it was relatively unchanged after 20 years? If serially (and cryptically) transmitted in humans, antigenic drift should have led to many changes after 2 decades.” Kilbourne concluded that the few changes in the virus over decades led to a troubling question:

Reactivation of a long dormant infection was a possibility, but the idea conflicts with all we know of the biology of the virus in which a latent phase has not been found. Had the virus been in a deep freeze? This was a disturbing thought because it implied concealed experimentation with live virus, perhaps in a vaccine.

In a 2015 paper, Michelle Rozo, of the U.S. Department of Defense, and Gigi Kwik Gronvall, of Johns Hopkins University, assessed the possible origins of H1N1 in the 1977 pandemic, based on the widely held conclusion that, “the 1977 strain was indeed too closely matched to decades-old strains to likely be a natural occurrence.”

They considered three possibilities for the 1977 re-emergence of H1N1: a laboratory accident, release as a biological weapon or a live-vaccine trial escape. They find less compelling evidence for the first two possibilities and conclude that there is a greater likelihood of a live-vaccine trial escape: “Whether this involved an ineffectively attenuated vaccine or a laboratory-cultivated challenge strain, the deliberate infection of several thousand people with H1N1 would be a plausible spark for the outbreak.”

Indeed in 2004, Palese, then at the Mount Sinai School of Medicine, reported an earlier personal communication from Dr. Chi-Ming Chu, a pioneer of molecular virology in China, who had died in 1998:

Although there is no hard evidence available, the introduction of this 1977 H1N1 virus is now thought to be the result of vaccine trials in the Far East involving the challenge of several thousand military recruits with live H1N1 virus (C.M. Chu, personal communication). Unfortunately, this H1N1 strain (and its descendants) has been circulating ever since . . .

Indeed, the 2009-2010 pandemic was a result of descendants of the 1977 re-emergence of the virus.

The debate over the origins of H1N1 in 1977 was — of course — highly political. Both the Soviet Union and China would potentially have been implicated in the event of a vaccine trial escape. For its part, in January, 1978 the WHO ruled out the possibility of a laboratory leak and in 1979 suggested that it may have come from chickens.

The 1977 re-emergence of H1N1 also became a topic of discussions in science policy debates over the regulation of so-called “gain of function” research involving potential pandemic pathogens. Laboratory escapes would implicate the research community and as a consequence might suggest limits on or tighter regulation of research with dangerous viruses. Vaccine trials gone bad, on the other hand, would likely implicate governments and public health officials rather than researchers.

My reading of the literature suggests that there is a strong consensus among relevant experts on the likelihood that the 1977 re-emergence of the H1N1 virus was a result of human error — most probably a vaccine trial escape. At the same time, there is not, to my knowledge, any official finding by an authoritative body such as the WHO on the origins of the virus.

One of the clear lessons of the re-emergence of H1N1 in 1977 is the pressing need for a global, independent investigative capability to understand and document the origins of pandemics. The obvious analogy is the forensic expert investigations that occur after natural disasters and airplane crashes. Pandemics are deeply political, it is true. But we should not allow challenging politics to stand in the way of learning important lessons for the future. Especially when the lessons involve learning how we can become less dangerous to ourselves.

They made a vaccine for this virus - and after 50 Guillain-Barré Syndrome deaths from this vaccine, they pulled it.

Why haven't covid vaccines been pulled yet?

8 year olds having heart attacks? Hello?

https://slaynews.com/news/8-year-old-vaccine-poster-child-dies-sudden-heart-attack/?utm_source=ground.news&utm_medium=referral

Many millions of future lives depend upon this action...

"One of the clear lessons of the re-emergence of H1N1 in 1977 is the pressing need for a global, independent investigative capability to understand and document the origins of pandemics. "