The Most Important Climate Paper I've Read this Year

Climate policy cannot succeed if it requires perpetuating global inequity

Note: There will be no Weekly Memo this week, as I’ve bothered you enough. We live in interesting times, for sure. Please consider sharing this post and helping this little community to grow and diversify. Thanks for reading!

In 2019, Mike Hulme warned of the myopia that might be induced by the totalizing rhetoric around targets and timetables of global climate policy. Hulme explained that there are far more dimensions to what constitutes a desirable future than found in a simple metric of global average surface temperature (emphases in original):

[H]ow one gets there matters more. . . than merely getting there. Means do matter more than ends. Or putting this differently, there are some futures beyond 1.5 degrees C (or even 2 degrees C) that are more desirable than other futures which do not exceed these warming thresholds. We should not mistake one set for the other.

A new and important pre-print out yesterday provides compelling evidence that we have indeed make that mistake, and in a big way. In fact, I believe it to be the most important climate paper I’ve read this year, and I’ve read a lot.

The new analysis, which has yet to go through peer review, is titled, “Equity Assessment of Global Mitigation Pathways in the IPCC Sixth Assessment Report” and written by Tejal Kanitkar, Akhil Mythri and T. Jayaraman, The paper makes strong claims about how the most recent Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) scenarios of climate policy “success” propagate historical global inequities far into the future.

IPCC scenarios are not simply academic exercises — they matter for the implementation of climate policies under the Framework Convention on Climate Change (FCCC) and across many other international, national and multilateral settings. These various policies have outcomes that affect real people. The scenarios of the IPCC not only help to shape policy, they also constrain our thinking about policy possibilities — In this case, we are guided myopically to futures that perpetuate global inequities.

The authors explain:

Our analysis of the regional trends underlying the global modelled scenarios in the IPCC’s 6th Assessment Report indicates that not only do the scenarios not “make explicit assumptions about global equity”, but they in fact project existing global inequities far into the future. The scenarios do not consider the differential energy needs of countries in the future based on their levels of development. Per capita GDP, consumption, and energy use remain significantly high in developed countries, even as most developing regions are projected to stay at very low levels of income, consumption of goods and services, and energy.

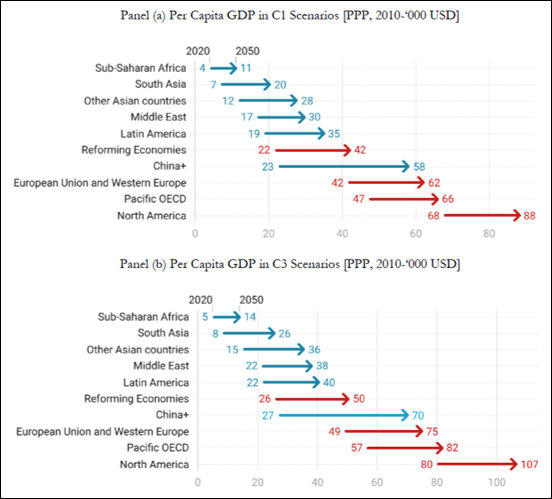

A few figures from their paper help to illustrate their conclusions about how scenarios project inequities into the future. The figure below shows how per capita wealth is projected to change from 2020 to 2050 under two categories (i.e., the two panels) of climate policy “success” across scenarios — I’m putting “success” into quotation marks to raise a question of the accuracy of that term in the context of these scenarios.

Sure, everyone gets richer by 2050 across the scenarios, but some much more than others. The rich today get a lot richer by 2050 while the poor today stay poor in 2050. People in OECD counties might look at that figure and smile — it looks pretty good with everyone $20,000 richer and climate targets are met — what’s not to like? Well, if you happen to live in Africa, in particular, you see that you are expected to fall even further behind. Sorry!

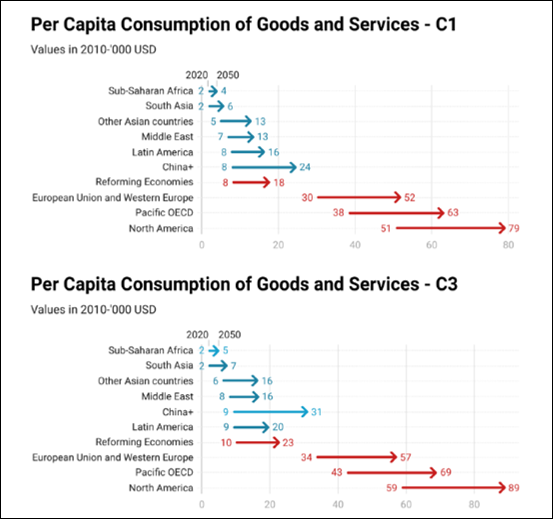

Inequities are even more stark in the figure below which shows changes in per capita consumption of goods and services for different regions from 2020 to 2050 under scenarios of climate policy “success.” I find this figure incredible because of the massive disparities it reveals that are built into the exercise.

A third figure, below, shows that the large additions to wealth and consumption of the rich world are fueled by fossil fuels much more so than in most other places around the world. This figure really helps to put into context recent efforts of policy makers in the United States and Europe to scold their counterparts across Africa for wanting to expand their use of fossil fuels.

The authors call out the remarkable hypocrisy on display here:

The IPCC AR6 scenarios disregard both the historical responsibility of the global North for carbon emissions as well as the future energy needs of the global South required to meet developmental goals. The burden of climate change mitigation is placed squarely on less developed countries, while developed countries continue to increase their energy consumption unhindered by constraints on the use of fossil fuels. The inequities between regions inherent in the scenarios are most striking when emissions and energy trends projected for North America are contrasted with those for Sub-Saharan Africa. Our results show that Africa, despite its very low contribution to historic emissions, is projected to bear a disproportionately high burden of climate change mitigation. Sub-Saharan Africa is projected to use zero coal by 2050, even as North America continues to rely on coal-based energy.

The authors are right to call out the IPCC and broader scientific community:

Scenario construction should effectively be the imagination of possible futures, and an equitable world must be central to this imagination. Our analysis clearly underlines the need for new frameworks for emissions modelling, scenario building, and constructing ideas of a future that makes the planet “liveable” for all and not just some sections of the global population.

This paper deserves to be widely read and discussed, not least because COP27 is about to kick off in Africa — a region that appears to bear much of the burden of climate policy “success” as envisioned across scenarios designed to map a path forward into the future.

Climate policy cannot be called a success if it leads to desired temperature targets but perpetuates global inequities, requiring that large parts of the world be excluded from the benefits of prosperity and abundance.

Comments are welcomed. Please share using the button below. And if you are not yet a subscriber, hit that button also. Have a great weekend!

Indeed horrible. Another example of what in the fields of agricultural and environmental development is sometimes called eco-colonialism.

Roger:-

I think the paper – or at least your framing of it – conflates two issues.

• The scenarios are, well, just scenarios: at least somewhat plausible projections of what might be the future.

Given the crime, corruption, civil wars and tribal conflicts in sub-Saharan Africa, increasing their per capita standard of living (using GDP as a proxy) by 3X in the next quarter century seems ... ambitious. Do those countries have the capacity (most importantly, human, social and cultural capital) to do better? Frankly, I'm a little dubious.

• The policies that are developed around those scenarios are the real issue, for me. For example, suppose we imagined a future that somehow sub-Saharan Africa achieves parity with the developed world, then we run the risk of creating another RCP 8.5, and its cloud of poor policies.

The problem with the policy-making is that the decision-makers haven't defined victory correctly. 1.5 C, 2 C shouldn't be goals; they're poorly-conceived and artificially created pseudo-goals that really have no meaning. Our goal as human beings should be to lift as many out of poverty as possible (OK, that's MY morality talking, others may not think of that as paramount.) no matter where or who they are. I personally see red whenever I hear people spouting off about doing away with fossil fuels EVERYWHERE which would doom those who are Without to live in continued penury no matter where they are.