In 2019, on the eve of the global COVID-19 pandemic, I published an analysis that took a deep dive on various metrics on state of football – the American kind. Based on these data I reached well-grounded yet provocative assertion that the United States was past “peak football.” Make no mistake, however, football remains the “king of sports” in the U.S. and is deeply ingrained into American culture. But its role is changing.

In this new series, I will take a deep dive into the future of American football across a number of dimensions. This series will be data-rich and will likely cause some dissonance. For instance, I will argue that football is – at the same time – becoming both more regional and more national, it is becoming less popular and yet more popular and it is also losing ground while remaining immensely popular. If this sounds like a bunch of contradictions, well, you’d be right. Welcome to America.

In today’s post I summarize a range of metrics on the state of football on the eve of the pandemic. Various data indicate a sport that had peaked – in participation, fan attendance and TV viewership – and was clearly in decline. In future posts I’ll bring these data up to date as much as possible given the disruption to the sport and data collection caused by the pandemic. In this post, I take a look at the state of football right before the pandemic hit in early 2020, as a baseline for future analyses.

The figure below summarizes a range of national trends in youth and high school participation, college game attendance and Super Bowl viewership, for two periods: 2010 to 2014 (in grey) and 2014 to 2018 (in black).

The data show that across indicators a decline in participation, attendance and viewership across most metrics is more than a decade in the making. The data also indicate that the decline accelerated towards the end of the decade, most significantly in youth participation.

The figure below shows that at the high school level, participation rates vary regionally across the United States. The smallest declines over the decade ending 2019 are concentrated in the southeast. Some places saw notable increases, concentrated in 5 states with universities that participate in the Southeastern Conference (SEC), which often dominates college football. Close observers will also be able to clearly see hints of the Mason-Dixon line — originating in the Missouri Compromise of 1820 that separated states that allowed slavery from those that did not (and a topic for a future in depth discussion).

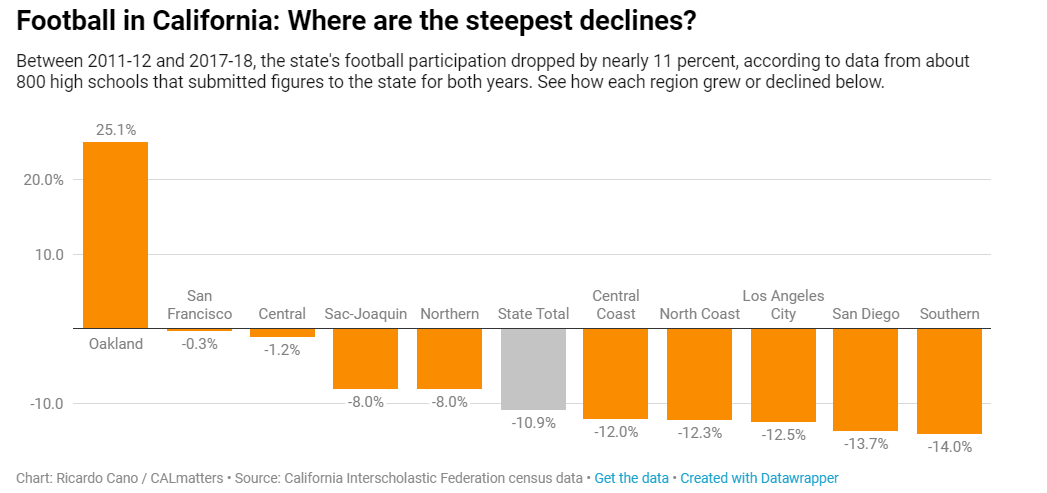

These data reflect an emerging trend: Football is becoming increasingly regional, especially at the youth and high school level. Although youth football is most popular in Texas and the southeast, trends are not uniform within regions. More granular data shows that within individual states decline is also regional. For instance the figure below from CALmatters shows that even as high school football participation declined in California by almost 11% from 2011 to 2017, that decline was not constant across the state. Oakland, for instance, saw a big increase.

We also see evidence of a decline in college football attendance. Using official data from the NCAA, in the Football Bowl Subdivision (the top division) maximum overall attendance occurred in 2013 at 38.1 million and then dropped by about 4% to 36.6 million in 2017, despite an increase in games played. In the lower Football Championship Subdivision, attendance reach a maximum in 2011 at 6.4 million, dropping by about 14% in 2017 to 5.5 million. For both subdivisions together, attendance peaked in 2013 (44.4 million) and dropped by about 5% in 2018 (42.1 million).

However, these data may be illusory. In 2018, in a very clever analysis Rachel Bachman of the Wall Street Journal looked at data on scanned tickets — those fans who actually attended the games. She found that actual attendance was much less than the official numbers, which are based on tickets sold and otherwise distributed:

College football has an attendance problem. Average announced attendance in football’s top division dropped for the fourth consecutive year last year, declining 7.6% in four years. But schools’ internal records show that the sport’s attendance woes go far beyond that.

The average count of tickets scanned at home games—the number of fans who actually show up—is about 71% of the attendance you see in a box score, according to data from the 2017 season collected by The Wall Street Journal.

It is a subject for a future post in this series, but the current realignment of major college football powers is, in my view, a reflection of the decline of the sport and a perceived need to nationalize its commercial offerings to be more like the NFL. Stay tuned for more on that.

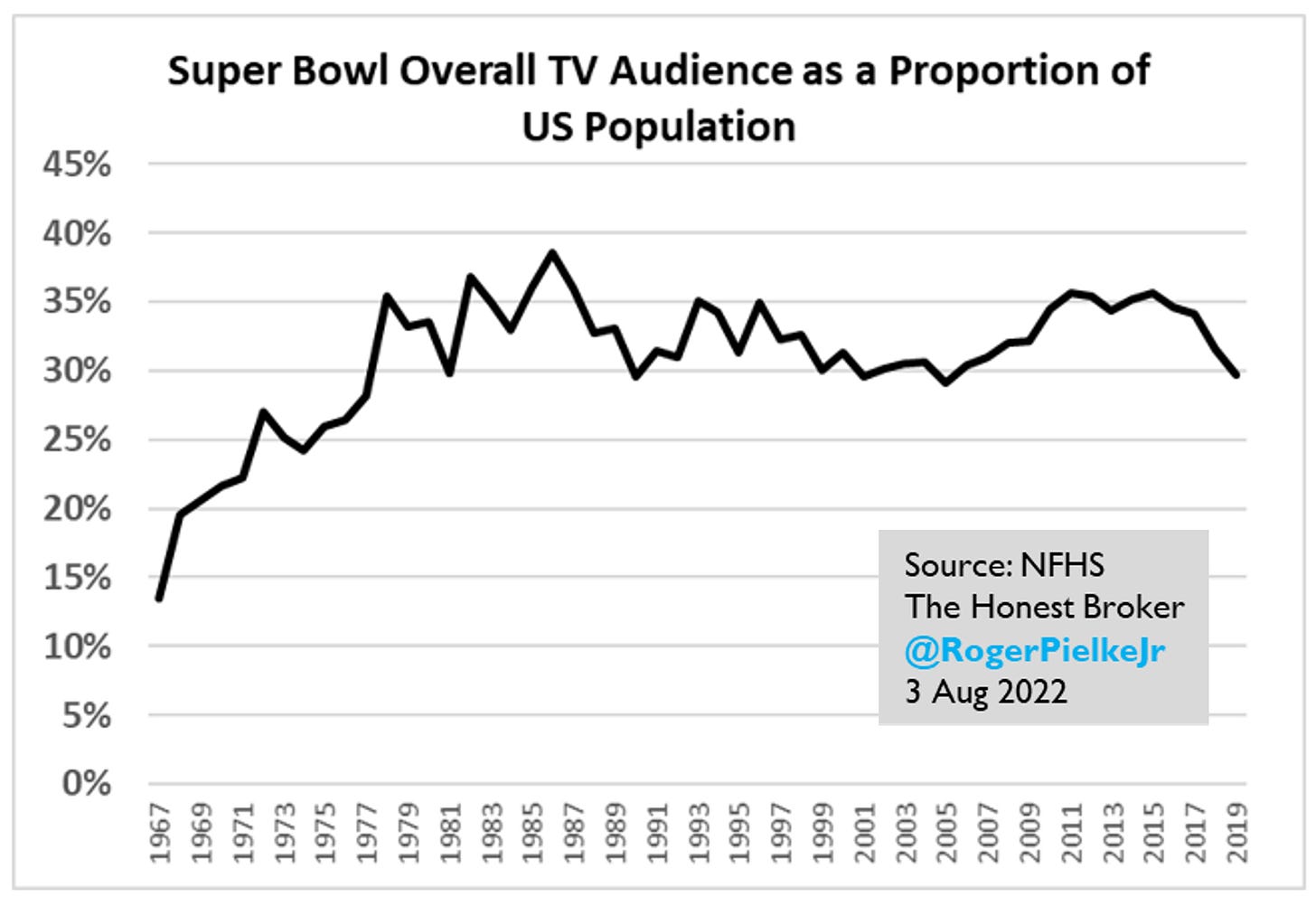

The last data I’d like to share today is on viewership of the Super Bowl. It is routinely the most watched television programming in the United States. However, in the years before the pandemic the big game saw a notable decline — viewership peaked in 2015 at 114.4 million, falling by more than 14% in 2019 to 98.2 million. The figure below shows Super Bowl viewership as a proportion of the U.S. population, which clearly shows the pre-pandemic decrease. Of course, the Super Bowl remained incredibly popular and a fixture of American culture..

To summarize: Across the board the data presented here show that despite its elevated status among sports in the United States, football has been in a state of relative decline over much of the past decade. The U.S. is past peak football.

Has the pandemic accelerated or mitigated that decline? In future posts in this series I will update these data as much as possible — in fall 2022 it will be really interesting to see what a return to “normal” actually looks like in these various metrics.

In this series I’ll also discuss some of the reasons behind these trends, including concerns over the safety of football, especially for children, but also for college and pro players. I’ll plan to spend some time discussing big time college football, which is of personal interest not least because leadership of the university that employs me believes so fervently in football that it is willing to transfer about $12 million per year in tuition revenues from academics to athletics (which is actually fairly modest compared to some universities).

Much here to discuss. Thanks for reading and following along. Please consider participating in the comments, where I will be happy to engage and learn from you.

If you like this sort of content, please consider a subscription at any level.

Data, sources and a much deeper dive: Pielke, R., Jr. (2019, August 27). After Peak Football: Trends in and Futures for America’s Most Popular Sport. https://doi.org/10.31236/osf.io/t5qsd