Science Diplomacy and The Pandemic Treaty

Here are five important science-related issues to include in any future global pandemic treaty

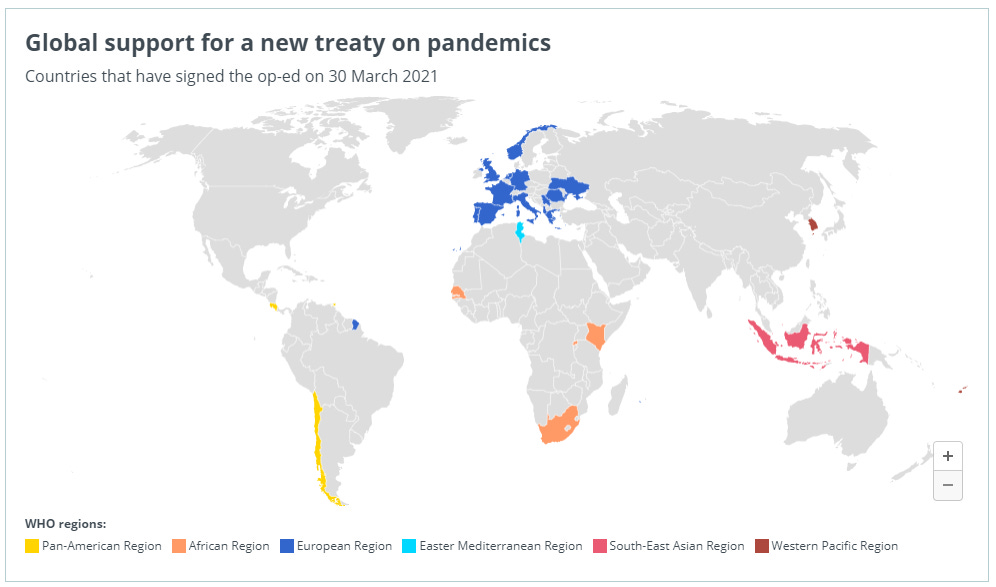

Last week Germany, South Korea and Indonesia were among 24 countries that along with the European Council and the World Health Organization who have called for a new global treaty for pandemic preparedness and response. This follows the commitment by the G7 nations to “exploring the potential value of a global health treaty.” One lesson we should take from Covid-19 is that a new global pandemic treaty is a good idea. Here I highlight five important science-related issues that should be included in a global pandemic treaty.

First, improve the process for the WHO’s declaration of a public health emergency. The International Health Regulations (2005) codifies the roles of WHO “Emergency Committees” to recommend the declaration a “public health emergency of international concern” (a PHEIC, the definition of which is guided by a formal “decision instrument”). However, a 2020 review by Lucia Mullen and colleagues of 66 statements issued by WHO Emergency Committees found “considerable inconsistency in the justifications dictating which criteria were considered to be met and how the criteria were considered to be satisfied.” Among the recommendations of the Mullen et al. review is that Emergency Committees:

“should only consider the available technical evidence of events when determine if criteria for a PHEIC are met rather than incorporating additional considerations in the deliberations such as the political implications.”

Navigating expert advice in highly political contexts is something we have learned a lot about during the pandemic and such knowledge should be reflected in how a pandemic treaty seeks to improve the WHO emergency declaration process.

Second, countries should agree on common standards for data collection and dissemination during a pandemic, to inform responses and enable relevant research to be undertaken. In the United States a group of journalists at The Atlantic began tracking Covid-19 early in the pandemic and soon learned — frighteningly — that:

“For months, the American government had no idea how many people were sick with COVID-19, how many were lying in hospitals, or how many had died. And the COVID Tracking Project at The Atlantic, started as a temporary volunteer effort, had become a de facto source of pandemic data for the United States.”

The data failures of the United States may be extreme, but they are not unique. Nations should agree to collect relevant, comparable data and to share that data, domestically and internationally, on timescales of decision making. Rich countries should agree to help provide resources, both financial and relevant expertise, to assist countries with less capacity to collect such data. A central data clearinghouse would facilitate dissemination, which today is undertaken mainly by volunteers, such as Our World in Data.

Third, nations should agree to establish international standards for the recommendation of vaccine and drug approval in a pandemic . The WHO observes:

“With the emerging global market the volume of biological medicinal products crossing national borders continues to rise, and it has become critical that regulatory knowledge and experience concerning them can be shared, and approaches to their control harmonized to the greatest extent possible”

Such harmonization would not be intended to replace existing regulatory approval processes within individual countries, but to facilitate such approvals by subjecting proposed treatments and vaccination to a common scientific evaluation of efficacy and safety, to facilitate domestic approval processes as well as the sharing of medical technologies across borders. In addition, there is a pressing need to develop and strengthen regulatory pathways in developing countries, which may have weak regulatory systems. The WHO “vaccines National Regulatory Authorities (NRA) strengthening programme” offers a foundation upon which to begin to better harmonize vaccine development and approval in emergency situations.

Fourth, nations should agree on procedures for investigations of pandemic origins. A good starting model can be found in procedures for the investigation of plane crashes under the provisions of the U.N Convention on International Civil Aviation. Its Annex 13 explains: “The sole objective of the investigation of an accident or incident shall be the prevention of accidents and incidents. It is not the purpose of this activity to apportion blame or liability.” However, as we have already seen with Covid-19, the politics of blame or potential responsibility are never far from questions of origins. That makes pandemic investigations trickier than plane crash investigations. However, air crash investigations can be politically complex also, such as the investigation into MH17, the Malaysian Airlines flight from Amsterdam to Kuala Lumpur that was shot down over Ukraine. That investigation was led by the Dutch Safety Board under the provisions of the UN Convention, which “formed the basis for a constructive cooperation between the states involved in the investigation: the Netherlands, Ukraine, Malaysia, the United States, the United Kingdom, Australia and the Russian Federation.” International agreement on air crash investigations have been developed over 60 years, so we should not expect similar provisions in a pandemic treaty to be initially as well developed or accepted, but it is important to begin to seek a similar agreement.

Fifth, and finally, regardless where the Covid-19 origins search leads, a pandemic treaty should include international regulations on research conducted on potential pandemic pathogens. In 2017 the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services recommended that “the US government should engage with other countries about policies concerning creation, transfer and use of enhanced PPP, encouraging the development of harmonized policy guidance.” Last year, Thomas V. Inglesby and Marc Lipsitch noted that “to our knowledge there has been no robust attempt at international consensus building or harmonization since the publication of this policy.” They further recommend,

“it would be in the interest of all countries if this work was restricted to the smallest number of laboratories that have globally exceptional records of biosafety and biosecurity, experience with dangerous pathogens of the type under study, staff training, strong security procedures, and state-of-the-art-facilities that operate under an appropriate national policy framework that ensures the safety of the work.”

Such a framework should not be limited to research that seeks to manipulate pathogens, but should also include research on all dangerous pathogens with pandemic potential. Now that we know how devastating a global pandemic can be, it would be irresponsible not to include stronger regulations on research conducted on potential pandemic pathogens.

Science diplomacy should comprise a third priority of any forthcoming global pandemic treaty, in addition to preparedness and response. In fact, it is difficult to envision improved preparedness and response without also addressing the five issue raised here.