Reefer Madness, Dodgy Science and Anti-Doping Policy

Sha'Carri Richardson's Ban from the Tokyo Olympics has Highlighted Questionable Science and Politics of Marijuana Regulation in Sport

U.S. sprinter Sha’Carri Richardson, a gold medal favorite, will miss the Tokyo Olympics after being suspended for one month following a positive doping test for marijuana. The facts surrounding Richardson’s suspension are not in question — she has admitted to the violation and World Anti-Doping Agency (WADA) regulations were properly followed.

As U.S. President Joe Biden explained:

The rules are the rules, and everybody knows what the rules were going in. Whether they should remain that — that should remain the rule is a different issue, but the rules are the rules.

In this post I’ll provide some important historical context to understand why marijuana — widely understood not to have performance-enhancing qualities — is on the anti-doping prohibited list in the first place. A close look reveals that the regulation of marijuana in international sport reflects a long-standing effort by the U.S. government to (mis)use WADA as a tool of domestic drug policy and WADA’s willingness to compromise scientific integrity to accommodate the U.S. influence.

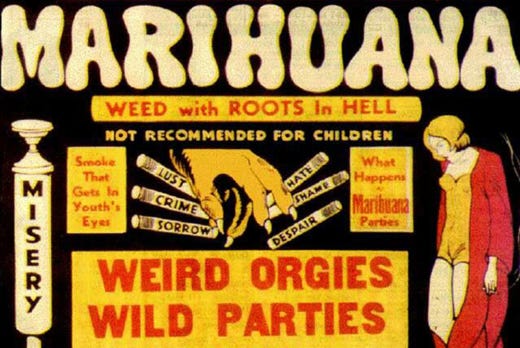

The U.S. government has a long history with marijuana. Mark Johnson, in his excellent book on the history of anti-doping Spitting in the Soup, observes:

Until the onset of the Great Depression in 1929, there was little public alarm about marijuana in the United States. Although cocaine and opiate abuse generated some earlier national concern, marijuana did not cause a moral panic until the early 1930s, when the drug became a proxy for fear of Mexican immigrants.

U.S. policy was heavily influenced by U.S. Department of Treasury official Harry J. Anslinger — his relentless pursuit of U.S. jazz musician Billie Holiday was recently chronicled in the film The U.S. vs. Billie Holliday. Anslinger wrote in 1937, the year in which Congress first passed U.S. federal legislation against marijuana, “It is difficult to estimate how many crimes, thrill murders, hold-ups, and sex offenses have resulted directly from the use of marihuana, but it is known that all marihuana users are degenerates.”

Of the 1937 federal legislation, Mark Johnson comments on the evidentiary basis for claims such as though made by Anslinger:

During the process of drawing up the [1937] legislation, lawmakers considered no medical or scientific testimony — primarily because there was no empirical evidence marijuana was addictive, nor any that showed it caused Mexicans (or anyone else) to pick up a knife, gun, or rock and murder innocents. With their conclusions about the immorality of pot already made, they had no use for evidence that challenged these assumptions. Foreshadowing the circumstances that led to the creation of WADA years later, pressure from religious temperance movements, anti-immigrant Anglo-Saxon race purifiers, and a depression exhausted public hungry to find someone to blame came together as a set of fears that was resistant to evidence.

Flash forward to the 1990s. A number of factors came together the accelerate demands for the creation of a new institution to oversee anti-doping in sport, notably the 1998 Festina affair in the Tour de France revealed widespread doping in cycling. Not long after, following many years of discussion, WADA was created under the auspices of the U.N. Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) International Convention against Doping in Sport. WADA is non-governmental — its rules are not laws of government, but agreed-upon regulations that international and national sports bodies agree to follow. One key role of WADA is to harmonize anti-doping regulations globally under the Olympic sports.

It is important to understand that when WADA was fist being formalized at the turn of the century, the International Olympic Committee (IOC) was in a period of relative political weakness due to the Olympic bribery scandal involving the Salt Lake City Games. Olympic Historian Bill Mallon observes, “At the beginning of 1999, investigating the IOC and the bid city process seemed to be all the rage,” with investigations initiated by the U.S. Olympic Committee and the U.S. Federal Bureau of Investigations. One influential member of the U.S. Congress even introduced a bill that would limit the ability of U.S. companies to sponsor the IOC, unless it implemented major reforms. The threats to IOC from the U.S. government were real and potentially consequential.

These political dynamics set the stage for the Clinton administration to extract concessions from the IOC as the new anti-doping institution and policies were being formalized. Among those concessions was the inclusion of marijuana on the list of prohibited substances and methods that the IOC would oversee (and which a few years later were transfer to WADA) and apply to athletes around the world.

The Clinton White House Office of National Drug Control Policy (ONDCP, which provides the U.S. funding contribution to WADA under the terms of the international doping convention) was explicit about its pressure campaign applied to IOC to include marijuana on its prohibited list. The Clinton administration bragged to the U.S. Congress:

ONDCP pushed the International Olympic Committee (IOC) to make marijuana a banned substance after an athlete who tested positive for marijuana was awarded the Olympic gold and hoisted up on the medal platform as a hero to all the world’s youth. The IOC responded and marijuana is now prohibited.

Darren Chalmers, a gold-medal winning Canadian snowboarder who had tested positive for marijuana in Nagano, was initially jailed in Japan and stripped of his medal. But it was returned within 36 hours after the Court of Arbitration for Sport ruled that the policies of the IOC and the FIS (which oversees skiing snowboarding) did not support any sanctions. The Clinton Administration used Chalmers as a justification for calling for marijuana regulations to be formalized under the new anti-doping regime.

Of course, the deeper reality was that the Clinton Administration’s focus was on using anti-doping to serve its domestic policy agenda focused on waging a “war on drugs.” The ONDCP admitted that neither athletes nor sports officials were much concerned about marijuana use in sport, having more concerns about actual performance-enhancing substances:

In the course of our efforts to put in place an IOC ban on marijuana, athletes and sports officials at all levels--ranging from Olympians to high school coaches to youth athletes--informed ONDCP that they felt that the more urgent drug threat within the sports world was the use of performance enhancing drugs.

Even so, President Clinton soon after issued an executive order that formalized drug regulation in sport as a part of broader U.S. government drug policy, with an emphasis on marijuana.

The use of international sports organizations to pursue domestic U.S. drug policies was bipartisan. For instance, in 2008 the George W. Bush administration reported to Congress that it had successfully resisted pressures from the international community to remove marijuana from the WADA prohibited list:

[O]ur leadership positions [in WADA] have enabled us to successfully resist calls from some entities to weaken international drug control efforts by removing controlled illicit substances such as marijuana and MDMA from WADA’s list of prohibited substances.

The inclusion of any substance on the WADA prohibited list is based on meeting two of three criteria:

potentially performance enhancing;

a health risk;

violates the “spirit of sport”

The first two are, in principle, based on evidence. For marijuana, meeting the evidence-based prohibited-list criteria has always been problematic, as the drug was initially placed on the list not because of its doping qualities, but because of broader U.S. drug policies. That led to constant debates as to the merits of its inclusion.

In 2011, WADA sought to address this debate by publishing a paper which alleged that marijuana in fact had performance-enhancing qualities. That paper was authored by two WADA employees and a U.S. government scientist who had been appointed to the WADA committee that recommends the prohibited list. Obviously, this was not an independent assessment, but one conducted by three researchers with an interest in the outcome, which was justifying the presence of marijuana on the prohibited list in support of U.S. drug policy.

A New York Times investigation published a few days ago identified significant problems with the 2011 paper, including:

“the 2011 analysis misstates the position expressed by a scientist named Jon Wagner in his 1989 paper titled “Abuse of Drugs Used to Enhance Athletic Performance.” The WADA paper asserts that Dr. Wagner “described cannabis as ergogenic,” meaning performance-enhancing. Dr. Wagner, a former assistant professor at the University of Nebraska who now works in the biotech industry, disagreed. “I didn’t write that,” Dr. Wagner said in an interview.”

“The WADA study also cites the authors of a 1996 paper, titled “Performance-Enhancing Drugs, Fair Competition, and Olympic Sport,” as making the claim that “cannabis could be performance enhancing in sports that require greater concentration.” In fact, the authors of the earlier paper took no position on whether marijuana is performance-enhancing and offered no scientific evidence that would support that position. Rather, they wrote that one argument holds that marijuana decreases performance while “some argue that it might enhance performance in sports that require great concentration.””

These problems aside, in fact, there is much more up-to-date science on the possibility of performance-enhancing qualities of marijuana in athletic competition. For instance a 2020 literature review by scientists unassociated with WADA concluded, “there appears to be no reason based on current data to believe that cannabis has any significant ergogenic [performance-enhancing] effect.” And an independent 2021 review concluded similarly, “does not act as a sport performance enhancing agent as raised by popular beliefs.”

Despite the more recent evidence from independent researchers, a WADA spokesman to the New York Times stated that the organization “stands by” the 2011 paper over the more recent research. This stubborn commitment by WADA to dated research (and clearly flawed) which was conducted by conflicted researchers is a great example of “policy-based research” where science is manufactured to support a pre-existing policy commitment. We wouldn’t accept tobacco company research on smoking, so why should we accept sport organization research on sport regulation?

Of course, while pointing out the compromised scientific integrity it is also possible to simultaneously empathize with the situation WADA finds itself in. The organization has for more than two decades faithfully and obediently followed U.S. demands to assist in supporting its domestic drug policy agenda, only now to find itself subject to criticism from U.S. policy makers. WADA officials must be shaking their heads at the irony.

WADA, in its response to the letter from Representatives Raskin and Ocasio-Cortez was not shy in noting the irony:

[A]t no time since the first Prohibited List was published in 2004 has WADA received any objection from U.S. stakeholders concerning the inclusion of cannabinoids on the Prohibited List. On the contrary, as has been reported by some media, the U.S. has been one of the most vocal and strong advocates for including cannabinoids on the Prohibited List. The meeting minutes and written submissions received from the U.S. over nearly two decades, in particular from USADA, have consistently advocated for cannabinoids to be included on the Prohibited List.

The lesson of all this is simple: WADA should simply follow its policies and procedures and not bend the rules or the evidence to satisfy the political demands of any of its stakeholders.

Marijuana regulation is not unique in presenting a challenge to scientific integrity in anti-doping regulation. As Erik Boye and I wrote in 2019 in a paper looking at scientific integrity and anti-doping regulation:

Remedies to better ground anti-doping regulation in evidence are neither complicated nor expensive, but they do require a renewed commitment among sport governance organizations as well as athletes, their sponsors, and governments.

The Biden Administration can better serve athletes, sport, science and integrity by abandoning the decades-old abuse of WADA to pursue deeply flawed domestic drug policies, and renew a national commitment to supporting evidence-based policy in anti-doping. For its part, WADA should also reassert the importance of evidence in following its regulations and act with more authority to keep domestic politics from compromising its regulatory mandate. In short, the U.S. and WADA should “Play True,” just like athletes.

Roger, fascinating insight into a hitherto little known fact; that the US Govt has been instrumental in shaping WADA's illicit drug policy for many years. Very interesting research. Regards, Daryl