Public Health and Climate Change

How to be an informed consumer of claims made in policy discussions

Later this week the Senate Budget Committee will hold a hearing on “the health costs of climate change.” Congressional hearings are always a bit of a hit-or-miss affair, and can easily devolve into partisan attacks on expert witnesses by politicians (of both parties). Here I’ll bypass the politics and offer two tips for anyone wanting to better understand claims made about projected public health effects of climate change.

Projections of the future climate and its possible impacts of human health require the use of scenarios of the future — these scenarios underpin both (a) projections made by earth system models for variables such as future extreme temperatures and (b) projections made by integrated assessment and economic models for variables such as human mortality and associated damage.

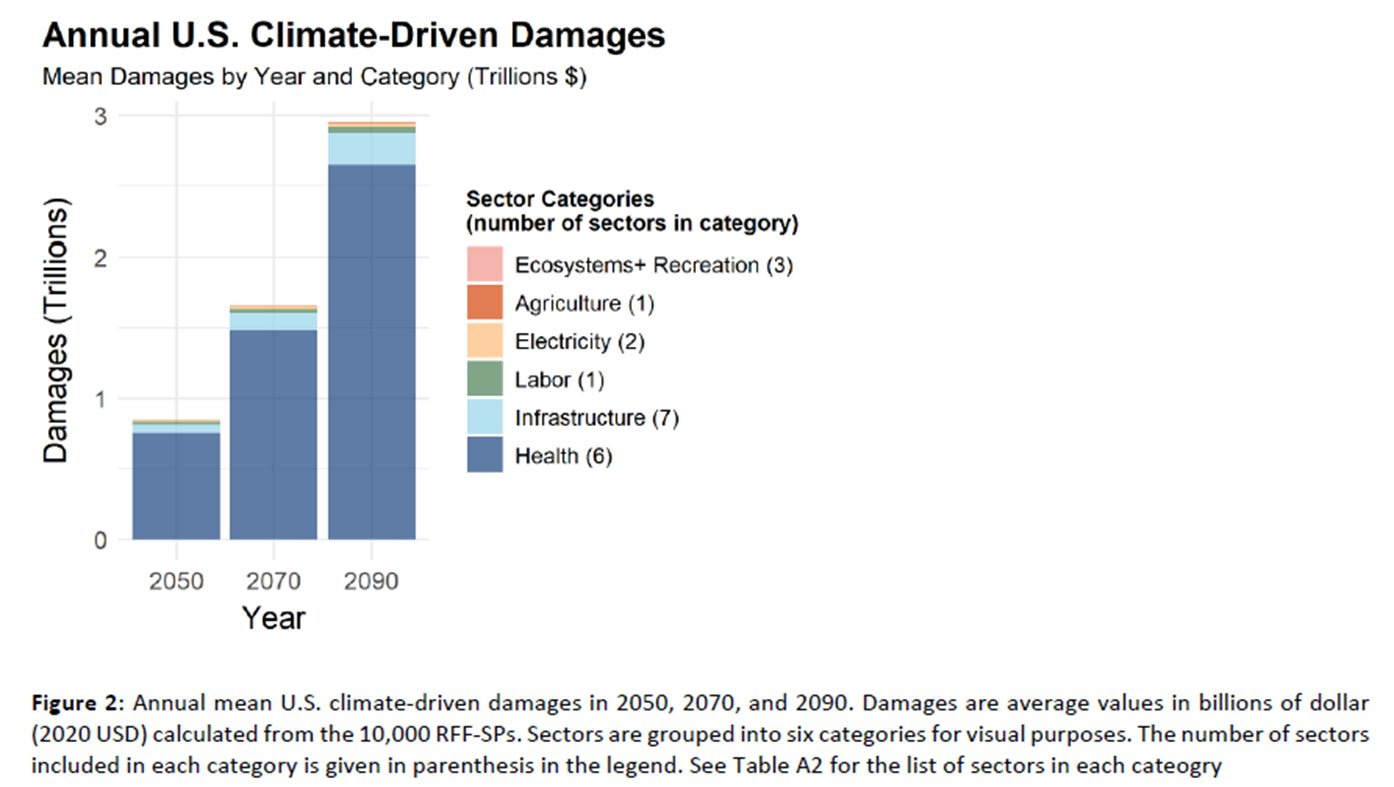

Such projections typically identify the effects of extreme high temperatures on human mortality as the most significant human health impact of climate change. In turn, the projected human health impacts of future climate change are typically the dominant cost of climate change from such analyses and thus a key factor in derived quantities such as the social cost of carbon and the projected economic benefits of climate mitigation.

For instance, a recent paper by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) being used to support Biden Administration climate policies identified human health impacts driven by projected future changes in extreme temperatures as the overwhelmingly dominant factors in projected future costs climate change, as you can see in the figure below.

The paper explains:

“national total damages in 2090 are primarily driven by the valuation of premature mortality attributable to climate-driven changes in extreme temperature (mean: $2.3 trillion per year; 95% CI: $0.31 – $9.9 trillion per year)”

The production of such claims is based on mind-numbingly complex methods that require considerable expertise and time to understand, much less replicate. Here I suggest two straightforward questions that anyone can ask and answer of such methods to better understand how the numbers were produced.

I hope that this week’s Senate hearing will focus more on questions such as the below, rather than on personal attacks and partisan politics. Call me an optimist if you must. But if not, we can still focus on these issues here.

Question 1: What scenarios are used to produce the estimates?

As frequent readers here will well know, the choice of scenario used in a climate projection can make the difference between an apocalyptic-looking future and one that appears much more manageable. You won’t be surprised to learn that many, if not most, studies that project future public health impacts of climate change rely on extreme, implausible or even impossible scenarios.

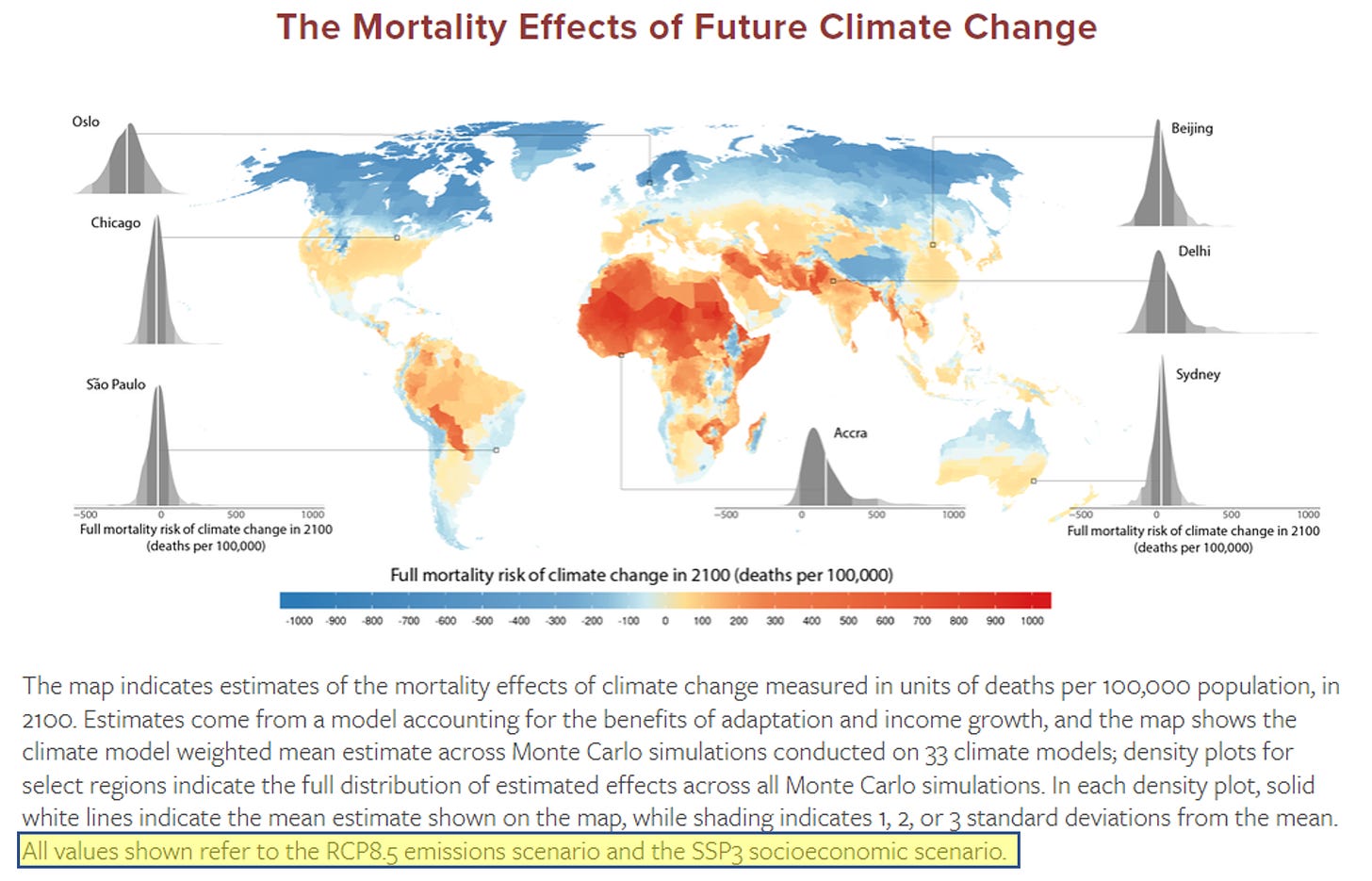

For example, a study that is central to the Biden Administration’s valuation of future climate damages — Carleton et al. 2022, which also plays a supporting role in the EPA study cited above — projects future impacts of extreme heat based on a scenario called SSP3-8.5. You can see this in their figure and caption below (with the yellow highlight added by me).

Here is a very big problem with this analysis — SSP3-8.5 does not exist. You read that right. It is a contrived scenario that maximizes future impacts, but is detached from both modeling and the real world. I won’t get too far into the gory details, but here is how Justin Ritchie and I characterized this type of scenario misuse, which relies on combining a worst-case socio-economic scenario (SSP3) with a worst-case climate forcing (8.5 watts per meter squared):

The combination of SSP3 and RCP8.5 was considered implausible by the SSP developers . . . Since the RCP8.5 scenario was the worst-case for greenhouse gas concentrations among the RCPs, there is sustained motivation to study the climate impacts of such a high level of greenhouse gases. Yet now the socioeconomics of the updated SSP5-8.5 indicate this climate forcing pathway is no longer truly a worst-case, because under the characteristics of the scenario the incredibly wealthy society which produces it could conceivably have ample resources to readily adapt to resulting changes in climate. Thus, a growing body of research utilizes the implausible SSP3-8.5 chimera which projects a poor and vulnerable global society in a high climate impact environment.

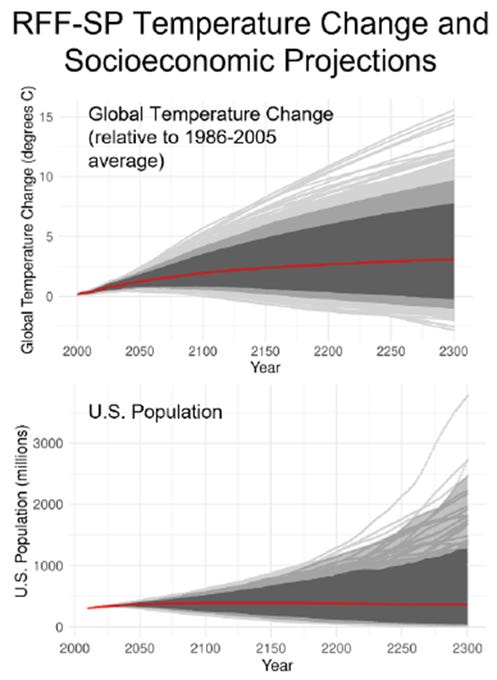

Here is another example. To produce estimates of future climate damage, the Biden Administration’s EPA relies on scenarios generated by Resources for the Future (RFF). You can see below the range of global temperature and U.S. population scenarios for 2100 of the RFF scenarios.

You can see that these scenarios include a 2100 projected global temperature change that ranges from -1 Celsius (yes, that is minus) to an increase of >7 Celsius relative to 1995. Similarly, projected 2300 US population ranges range from near zero (zombie apocalypse?) to ~3.75 billion. You don’t have to be a climate scientist or a demographer to see some considerable ridiculousness in play here.

Yet, the resulting methodology used to convert scenarios into projected future health impacts takes averages across all these scenarios, giving outsized weighting to the most extreme values. The result are projections far more extreme than if made using more plausible representations of climate and population futures.

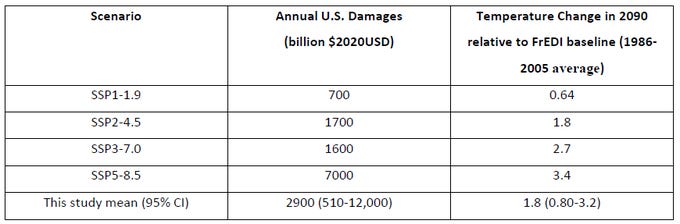

Shown in the table below is the bottom line result from the EPA analysis, which clearly shows that extreme assumptions are the handmaiden to extreme results.

The table shows that the mean result for U.S. damages from the EPA study lies between two scenarios now judged to be implausible (or if you prefer, “low likelihood” in the calibrated language of the IPCC) — SSP3-7.0 and SSP5-8.5. Instead, the Framework Convention on Climate Change views SSP2-4.5 as an upper bound on the current global emissions trajectory, and our work suggests a mid-range scenario of SSP2-3.4, which is no where to be found in this analysis.

Extreme scenarios produce extreme results. They also create a false impression of the benefits of mitigation, as they start from unrealistically high results. Climate policy discussions deserve more realistically-grounded analyses. My advice: ask the question, what scenarios are you using to produce your results?

Question 2: How your analysis factor in adaptation?

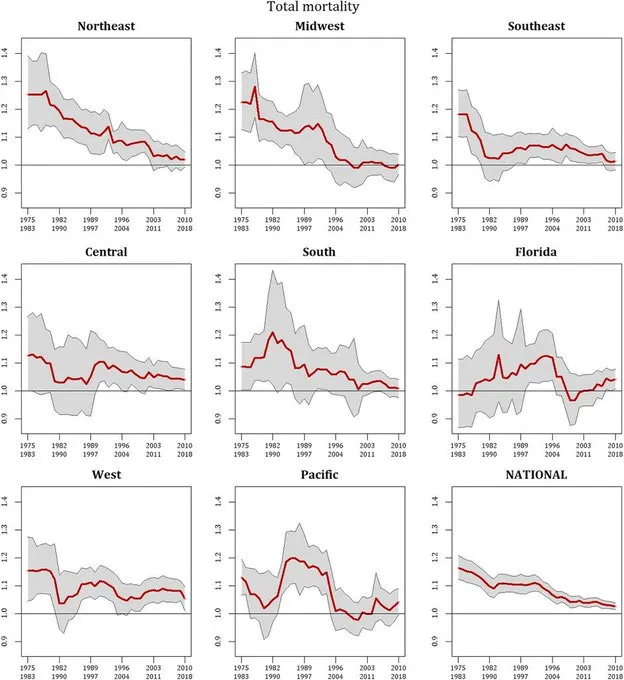

One of the most incredible success stories of science, technology and policy over the past century has been the incredible progress around the world in improving adaptative capacity to weather and climate. This success story rarely gets reported on but that makes it no less real. There is of course more to do and continuing efforts are needed to maintain the progress made to date.

One dirty little secret in most studies of the future impacts of climate change (and not just on the effects of changes in extreme temperatures) in that future adaptation to climate variability and change is simply left out of projections. Assumptions are made that the climate will change, but people’s behavior will not. This is not how the real world works.

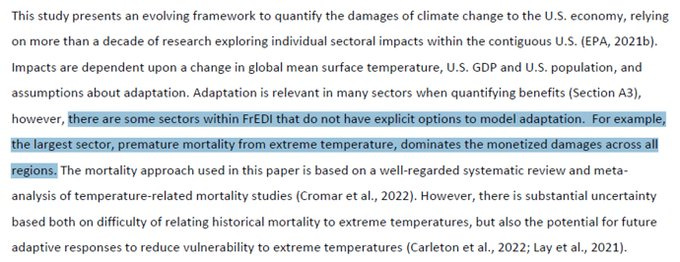

Consider the EPA study discussed above. Deep in the methods section, here is what it says about future adaptation to change, which it neglects to include in its methodology:

Why does adaptation matter? Consider the judgment of the World Health Organization on what happens to projections of the future impacts of extreme temperatures when adaptation is considered (emphasis added):

As expected, the estimates are reduced when adaptation is assumed, and the attributable mortality is zero when 100% adaptation is assumed.

Of course, adaptive success may never reach 100%, but history shows that it can make a huge difference in outcomes, as shown in the figure below, which shows that U.S. heat mortality decreased dramatically most everywhere over the past 50 years even as the incidence of heat waves has increased. This is very good news.

Adaptation is not a substitute for mitigation, of course — they are complements. However, any study that purports to demonstrate the value of mitigation to the future effects of climate change without considering adaptation is flawed and potentially misleading.

As you interpret claims made about future climate impacts, always ask, how is adaptation considered in any analysis that seeks to project the future human health impacts of climate change?

After spending much of the past spring in Southeast Asia, and breathing a lot of bad air, I am certain that there are enormous benefits to human health by reducing fossil fuel consumption in order to decrease particulate air pollution. But that’s a topic for another day.

Your comments are welcomed. So too is sharing this post, maybe even to members of the Senate Budget Committee!

I appreciate your support. I am embarking on an experiment to see if a new type of scholarship is possible. I am looking to make a break from traditional academia and its many pathologies, and this Substack is how I’m trying to make that break. I am well on my way. Please consider a subscription at any level, and sharing is most appreciated. Independent expert voices are going to be a key part of our media ecosystem going forward and I am thrilled to be playing a part. You make that possible. Thank you!

And let me add - if Greenstone or anyone else whose work is discussed here would like to comment, they are invited to do so, I encourage it in fact. They can email me directly with permission to post if they happen to be among those few people still not yet subscribed here ;-)

As I've stated many times and even published in the Wall Street Journal, cost is an accounting term that only has relevance when used in context with benefit. But no one on the left wants to acknowledge the benefits of using fossil fuels to enhance life on earth for humans.