Martin Luther King's Ask of Social Scientists

Scholarship on societal problems has come a long way, but still has much further to go

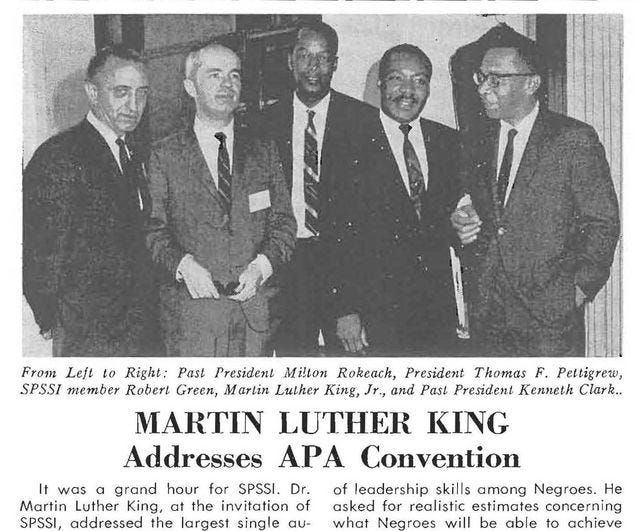

In 1967 Martin Luther King spoke at the annual meeting of the American Psychological Association (APA) on “The Role of the Behavioral Scientist in the Civil Rights Movement.” King acknowledged something too often lost in the daily stresses of contemporary academia: “For social scientists, the opportunity to serve in a life-giving purpose is a humanist challenge of rare distinction.” Today, I look back on Dr. King’s ask of us social scientists, how well we’ve done, and how much more we have left to do.

The idea that social scientists should have a role in helping to characterize societal issues as problems and to develop possible alternatives has long been a point of debate among scholars. Some emphasize detachment from current affairs, others engagement. Heinz Eulau, a leading political scientist, wrote contemporaneously with King’s speech that, “political science, if taken seriously as a science, has no easy answers that might cure the world's social and political ills.” Within the social sciences some academics of the era focused on making their research more “scientific” — that is both theoretically grounded and empirically based — while others took a more pragmatic turn towards problem-oriented inquiry.

Dr. King acknowledged both approaches to social science, but ultimately emphasized their relevance to contemporary issues. He highlighted that the entirety of the field had a notable blind spot when it came to race: “Negroes want the social scientist to address the white community and 'tell it like it is.' White America has an appalling lack of knowledge concerning the reality of Negro life.”

He explained that the civil rights movement of the 1960s — including civil disobedience, violence, riots — should have come as no surprise to anyone who had been paying attention: “Science should have been employed more fully to warn us that the Negro, after 350 years of handicaps, mired in an intricate network of contemporary barriers, could not be ushered into equality by tentative and superficial changes.” He observed that “urban riots” were understandable in terms of a “social phenomena”:

Urban riots must now be recognized as durable social phenomena. They may be deplored, but they are there and should be understood. Urban riots are a special form of violence. They are not insurrections. The rioters are not seeking to seize territory or to attain control of institutions. They are mainly intended to shock the white community. They are a distorted form of social protest.

Dr. King observed, astutely, that the social sciences often deal in uncomfortable knowledge: “These are often difficult things to say but I have come to see more and more that it is necessary to utter the truth in order to deal with the great problems that we face in our society.”

In a clear understatement, he noted that there were many opportunities for social science research “to assist the civil rights movement.” Three examples he cited were research on leadership in the Black community, the effectiveness of political action of the civil rights movement, and psychological and ideological changes within the Black community as societal change occurs.

Ultimately, Dr. King asked social scientists to help gauge progress, including assessments of direction and pace: “Are we moving away, not from integration, but from the society which made it a problem in the first place? How deep and at what rate of speed is this process occurring? These are some vital questions to be answered if we are to have a clear sense of our direction.” Such questions are fundamental to all policy research.

Today, it may be difficult for academics to understand how profoundly disruptive Dr. King’s call was, not just in the context of academic traditions, but also the outright racism within academic itself. Just months before King’s address to the APA, Charles Loomis of Michigan State University, in his presidential address the American Sociological Association, argued that the U.S. government should negotiate with Ecuador, Peru or Bolivia to establish a “second Israel” where black Americans could create a new society. Loomis argued, “it’s better not to have concentration camps — and they will become an option here before long with the riots.”

Fortunately, academia listened to King rather than Loomis. In 2018, a special issue of the Journal of Social Issues looked back at Dr. King’s call 50 years later. Thomas Pettigrew, professor at the University of California Santa Cruz (and who had extended the 1967 invitation to speak to the APA) summed up the social science response of the previous half-century, giving a mixed verdict:

[W]e can only give a mixed answer to the key question as to whether we have answered Dr. King’s 1967 call. In general, [the social sciences] have done reasonably well in researching much of what Dr. King called for a half century ago. But the hard truth is that we have failed to communicate our findings sufficiently to the public; thus, the full meaning of this large body of work has been effectively resisted by many white Americans. We need only to recall the 2016 presidential election and its callous aftermath—the Charlottesville debacle, the numerous police shootings of Black males, etc., to witness the enduring racist underside of America (Pettigrew 2017).

While the social sciences have diversified significantly since the 1960s in terms of both scholars and scholarship, the various disciplines that comprise the social sciences still have a long way still to go. For instance, top university social science departments continue to be overwhelmingly populated by white males, and Black and Latino students continue to be under-represented on our leading campuses. Fulfilling the promise of social science research to contribute to addressing societal problems remains a work in progress.

Ultimately, Dr. King asked that “we must reaffirm our belief in building a democratic society, in which Blacks and Whites can live together as brothers, where we will all come to see that integration is not a problem, but an opportunity to participate in the beauty of diversity.” We in the social sciences have an important role to play in meeting this humanist challenge.

Roger I riffed a bit on your post here https://forestpolicypub.com/2021/01/18/dr-king-and-the-role-of-social-scientists-in-the-civil-rights-movement/ Thanks for Posting!