How to Regulate Gain-of-Function Research

An obvious approach to clarifying risks vs. benefits

Back in 2001 NASA contacted me to help them make a decision about the timing of re-entry of an Earth observation satellite. Their Tropical Rainfall Measurement Mission (TRMM) was scheduled to soon undergo a controlled re-entry somewhere in the remote Pacific Ocean.

However, TRMM was producing novel data that had proven useful in operational weather forecasting and in climate research. If the mission could be extended, the collection of that valuable data would continue. But continuing the mission would consume fuel that had been allocated to the controlled re-entry, meaning that eventually TRMM would tumble back to Earth uncontrollably.

The decision was one about balancing risks and benefits: A controlled re-entry meant zero risks to anyone on the ground, but a certain loss of continuing to collect valuable precipitation data. An uncontrolled re-entry meant risks for those on the ground, but a guarantee of collecting valuable data. I organized a workshop to help inform NASA’s decision making by clarifying and quantifying risks versus benefits of the different re-entry options.

Benefit-risk trade-offs are ubiquitous in policy making, and a lot of policy research involves trying to characterize risks and benefits in ways that inform decision making. Of course, such characterizations are usually complicated by the fact that different stakeholders have preferences for how they’d like the decision to be made well before any such benefit-risk characterization.

For the TRMM re-entry decision, it was clear that different participants had views shaped by how they valued the risks and benefits. For instance, some scientists valued doing more research over the possibility of on-the-ground risks of uncontrolled re-entry. At the same time, political officials high-up in NASA worried about the huge geopolitical and reputational consequences of an uncontrolled U.S. satellite crashing somewhere around the world, maybe harming or killing people.

A few weeks ago the Biden administration requested input on proposed new regulations governing biological research that poses risks but also offers possible benefits — notably research that enhances pathogen, commonly called gain-of-function (GoF) research.

They explained:

Life sciences research is essential to the scientific advances that underpin improvements in the health and safety of the public, agricultural crops, and other plants, animals, and the environment. While life sciences research provides enormous benefits to society, there can be risks associated with certain subsets of work, typically related to biosafety and biosecurity, that can and should be mitigated.

The basis for soliciting input on possible new regulations resulted from a report earlier this year from the National Science Advisory Board for Biosecurity. That report highlighted the stakes:

[B]iosafety and biosecurity risks associated with undertaking research involving pathogens include the possibility of laboratory accidents and the deliberate misuse of the information or products generated. In particular, research having the potential to enhance the ability of pathogens to cause harm has elicited concerns and policy action. Such research may help define the fundamental nature of human-pathogen interactions, thereby enabling assessment of the pandemic potential of emerging infectious agents, informing public health and preparedness efforts, and furthering medical countermeasure development. It is of vital importance that the risks of such research be properly assessed and appropriately mitigated and that the anticipated scientific and social benefits of such research is sufficient to justify any remaining risks.

Public discussions and debates offer little hope of clarifying risks and benefits associated with risky biological research, not least because the origins of SARS-CoV-2 are not yet settled, and the possibility that it may have resulted from risky research remains a possibility. Researchers with relevant expertise have become loud partisans, which makes it difficult to properly assess trade-offs.

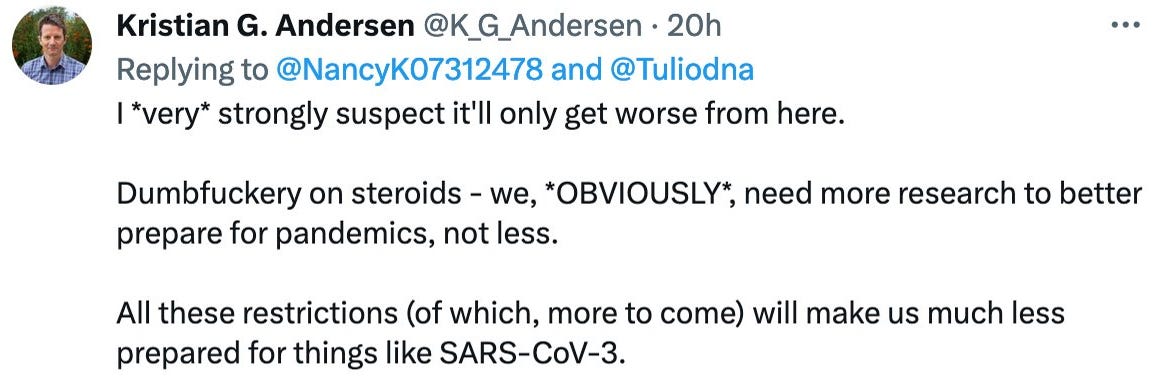

For example, some researchers implicated by new regulations don’t want any restrictions on their work. Kristian Andersen, who in his public statements vehemently opposes the possibility of a research-related origin of Covid-19, took to X/Twitter this week to call the Biden Administration's request for input on proposed new regulations on research — “dumbfuckery on steroids” (below).

On the other side of the debate, for instance, Justin Kinney and Richard Ebright have called for outright bans on “the highest-risk type of pathogen research.” There is no overlap in these different perspectives.

Expert conflict creates a conundrum for decision making: In the context of dueling experts and intense public debates, how should policy be made regulating risky biological research, recognizing very real risks but also potential benefits?

One approach that makes a lot of sense to me would be for governments to agree that risky pandemic research should only be conducted if it can be insured by the private sector against laboratory-related incidents that lead to harm, perhaps as part of a global pandemic treaty.

A requirement for required liability insurance was proposed in 2016 in a Policy Working Paper of the Future of Humanity Institute at Oxford University (Cotton-Barratt et al. 2016). They explain:

Laboratories conducting experiments in the appropriate class could be mandated to purchase insurance against liability claims arising from accidents associated with their research. Ideally, this research should be explicitly classified as an "inherently dangerous activity" by the legislature. This will establish strict liability for any damages caused by accidents, which means that laboratories would be liable even if there was no negligence. Strict liability is already legally established for other inherently dangerous activities analogous to this research, and might well be the legal standard used in many common law jurisdictions in a GoF case even without legislative intervention. The advantage of making this clearly established is that it would provide laboratories with strong incentives to minimise risk.

Last week in London I asked a couple of reinsurance leaders if gain-of-function research was an insurable risk. Their answer was “sure,” but only up to the level of “tail risk” which would pose an existential threat to insurers. Consider that the economic impacts of Covid-19 have been estimated at $16 trillion, while capital in the reinsurance market (2022) was $638 billion. Any agreement to require liability insurance for risky research would thus also need to be accompanied by a agreed upon cap on that liability.

Requiring explicit liability insurance for institutions that conduct risky biological research makes sense for a number of reasons:

It would lead to independent assessments of the risks and benefits, moving the debate away from those with an interest in the outcome of regulation. With big money at stake, the private sector is less likely to play games with risk assessment.

It would result in financial estimates of the costs to insure against risks, which would inform government decisions about research priorities. Would risky research be still worth doing if funding agencies or research institutions had to bear the costs of insuring those risks? Science policy decisions would be more informed with such information.

Liability insurance would create strong incentives for research institutions, including universities, to more rigorously oversee risky research and invest more resources in enforcing safety standards. Research institutions and researchers would also need to have some degree of liability to protect against any moral hazard associated with insured liability.

It is conceivable that some types of risky research are simply uninsurable. If so, this would send a very strong signal to policy makers and the public that such research ought not be performed simply due to being too risky.

There are also some challenges associated with implementing a requirement for insuring liability associated with risky biological research:

Some countries might readily participate in such a regime, but others might simply ignore the requirement and conduct risky research anyway. Nuclear non-proliferation might offer a useful model.

In some countries, risky research is no doubt performed by the military or otherwise in secret. Such research would sit outside the reach of any insured liability agreement.

It may be difficult or impossible to assess true risks, as most of those with necessary expertise would also be members of the community subject to the consequences of an insured liability requirement. The partisan politics of research regulation might then simply reappear in the insurance context. Perhaps in response, governments would thus have a greater motivation to properly assess risks to avoid regulatory capture of advisory mechanisms.

Harmonizing a liability requirement across participating nations may be challenging. However, this would not stand in the way of, say, the United States or the European Union unilaterally implementing such a requirement.

One possible outcome of initiating a discussion of a proposal for an insured liability requirement would be that as part of this discussion people would start to quantify the financial implications of such a proposal. That alone would be worthwhile, whether not any such requirement is adopted.

Science academies or other leading organizations need not await government interest in insured liability for risky research. A workshop that seeks to quantify the financial implications — for research and for liability — of an insured liability requirement would certainly add important context to the ongoing discussion of the Biden Administration’s proposed new regulatory policies.

My view is that once we start having this discussion we will quickly learn that there are indeed some types of research that are simply uninsurable. If so, then those areas of research should be leading candidates for extremely strong regulation and perhaps even defined as research no-go zones.

After we held our workshop on the TRMM satellite in 2001, NASA decided to extend the mission and take the risk of an uncontrolled re-entry of the satellite. Our workshop estimated the risks of harm to any person due to an uncontrolled re-entry was 1 in 5,000. In 2015, the TRMM satellite re-entered the atmosphere and fell harmlessly into the Indian Ocean. Benefit-risk estimates don’t make decisions for us, but they can make those decisions better informed.

Thanks for reading! Comments welcomed. Please like and share. If you are a subscriber, thank you! If not, you are invited to join the THB community and participate in our discussions.

It's hard to fathom that an insurance company would issue a policy to a US Government agency funding clearly dangerous research that is subcontracted to a private US company that then subcontracts part of that research to a Chinese Government Lab that has been repeatedly cited for unsafe practices.

Science is, at bottom, formalized curiosity: "run and find out" and many scientists, like Anderson, bristle at any restrictions on pursuing his curiosity.

Let's step back. What benefit is there to "gain of function" research? The work itself manipulates a pathogen to make it more virulent, more contagious. To what end? Nature itself rolls the genetic dice to come up with features that may be those things but the features born in the lab are bogglingly unlikely to be those features that Nature comes up with so, for instance, a vaccine based on a lab-invented germ can have only one use: as part of a bio-warfare program. The vaccine developed based on an invented germ is unlikely to have the features needed to identify and neutralize the natural germ. It -may- be insurance against a lab accident but that's it. It's most likely an adjunct to a covert bio-war program