In my previous post I explained the two primary ways that carbon dioxide emissions change the climate. The emission of carbon dioxide from the burning of fossil fuels and other activities is the most important human climate forcing increasing global average surface temperatures. The Paris Agreement uses changes in global average surface temperature to frame its overall objective, in the familiar 1.5 and 2 degree Celsius temperature targets.

However, there are more influences on the climate than just the influences of added carbon dioxide – and notably on regional climate where people and species actually live.

In today’s post I explain how changes to the land surface can have profound impacts on regional climates, in some cases as large as or larger than the regional effects of increasing carbon dioxide to the atmosphere. Land use, as I’ll refer to all such changes, is the consequence of billions of people over centuries and more utilizing and transforming the Earth’s surface as we grow food, build cities, flood valleys and just about everything associated with human activity.

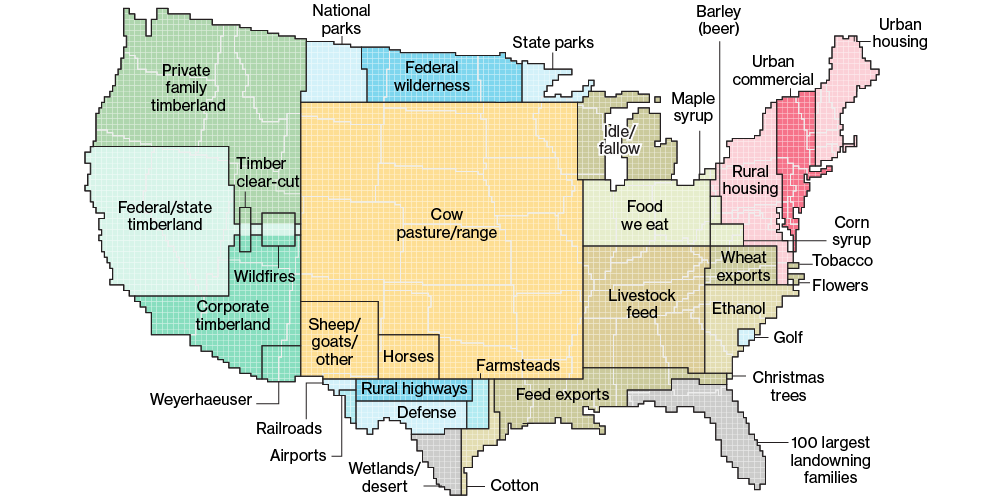

Anyone who has looked out of the window of an airplane knows well that people have transformed the land in profound ways. The figure below illustrates different land uses across the United States. There is no place that is untouched by humans.

Large-scale alterations to the land surface can affect the weather and climate. For example, changing the land surface can alter albedo (its reflectivity of solar radiation back into space) which directly alters sensible heat (heat that we can measure with a thermometer) and latent heat (which is in the form of water vapor) mixed into the atmosphere.

There are many peer reviewed papers that have for decades convincingly shown that land use can change regional climate. For instance, Gordon Bonan, a climate scientist at the National Center for Atmospheric Research in Boulder, Colorado, explained the significance research that I led on the effects of land use on the weather and climate of south Florida:

“Nobody experiences the effect of a half a degree increase in global mean temperature. What we experience are the changes in the climate in the place where we live, and those changes might be large. Land cover change is as big an influence on regional and local climate and weather as doubled atmospheric carbon dioxide—perhaps even bigger….. Climate change is about more than a change in global temperature. It’s about changes in weather patterns across the Earth… The land is where we live. This research shows that the land itself exerts a first order [primary] influence on the climate we experience.”

Let’s take a closer look at land use effects on south Florida, which I have studied for more than 50 years. The figure below shows how southern Florida’s land use changed from 1900 to 1992.

In order to assess how these changes affect the region’s weather and climate, we used a model run in two simulations. Both simulations started with identical large scale weather patterns for July and August, which is in the rainy season in Florida. We used two different land surfaces in the model runs -- respectively, the 1900 and 1992 landscapes which you see illustrated above – and then ran the models to explore what effects the differences might have on weather.

The effects of different land surfaces on South Florida’s weather and climate turned out to be significant. Averaged across the region, the July and August precipitation under 1992 land use was about 12 percent less than it was using Florida’s 1900 landscape.

The figure below shows the change in rainfall across the peninsula, which were spatially complex. Daytime maximum temperatures also increased in urbanized areas and inland by up to four degrees Celsius.

That land use change significantly alters regional climate from what it would be in the absence of humans is unambiguous. Many studies from around the world have shown that land surface alterations can have detectable influences on weather and climate. Here are just a few recent examples:

Seasonal tropospheric cooling in Northeast China associated with cropland expansion

Increasing heavy rainfall events in south India due to changing land use and land cover

Central Taiwan’s hydroclimate in response to land use/cover change

Importantly, human alterations in the land not only affect weather and climate where the land use changes occur, but can also substantially influence regional climate thousands of kilometers away.

To understand how this happens, consider as an analogy that El Niño and La Niña events – which are changes in Pacific Ocean temperatures – can significantly alter regional climate thousands of kilometers from the region. These long-distance influences are called teleconnections. Thus, changing the land surface over large areas could have similar major climate effects through teleconnections.

Of course, El Niño and La Niña conditions fluctuate back and forth, so it is easier scientifically to extract the statistics of their effects compared to teasing out the signals of long term changes in land use. Nonetheless, since regional changes in surface heat and moisture forcing from the human changes to the natural land are comparable in magnitude with ENSO events, long -term regional climate change has been hypothesized to result from land use.

And this is what research has shown. For example, one modeling study showed that tropical deforestation can affect precipitation patterns thousands of miles away and on different continents.

That paper concluded:

“deforestation of tropical regions [would] affect precipitation at mid- and high latitudes through hydrometeorological teleconnections. In particular, it is found that the deforestation of Amazonia and Central Africa severely reduces rainfall in the lower U.S. Midwest during the spring and summer seasons and in the upper U.S. Midwest during the winter and spring, respectively, when water is crucial for agricultural productivity in these regions. Deforestation of Southeast Asia affects China and the Balkan Peninsula most significantly. On the other hand, the elimination of any of these tropical forests considerably enhances summer rainfall in the southern tip of the Arabian Peninsula. The combined effect of deforestation of these three tropical regions causes a significant decrease in winter precipitation in California and seems to generate a cumulative enhancement of precipitation during the summer in the southern tip of the Arabian Peninsula”

The figure below from their study shows the regions deforested in their modeling research .

More recent research bolsters the conclusion of remote effects from land use change and land management. Here just a few recent examples:

Local and teleconnected temperature effects of afforestation and vegetation greening in China

Land Use and Wildfire: A Review of Local Interactions and Teleconnections

Remote land use impacts on river flows through atmospheric teleconnections

The magnitude of “teleconnection” effects is a continuing focus of research for actual past and projected land use changes, but remote influences have been well documented.

The human effect on climate is significant and multi-dimensional. Changes in land use can affect regional climate as well as the climates of regions far removed from where the land use occurs. The complexities of the human influences on climate challenge simple assertions of attribution for observed changes and create significant obstacles to the skillful projection of how regional climates might change in the future.

The important point in this article is the fact of pointing out other factors affecting the climate than just CO2. When a theory claims that a certain factor (eg CO2) is the cause of a phenomenon being studied (warming), the scientist has an obligation not only to show that the factor is the cause, but also an obligation to rule out other factors that could be contributing. Dr Pielke is correct to show that human land use may be as important or even more so than CO2 in regional climate phenomena. This essential part of the scientific method is shockingly rare or non-existent in the literature supposedly attributing warming to human-sourced CO2.

The map of the 48 States is far from accurate. For example, a large part of the Midwest are States are named cow pasture. This includes Missouri, Iowa, and much of Minnesota which are actually used largely for row crops. Corn being the major crop. The time when almost every farmer had a few milk cows was disappearing 80 years ago in these states. Also, Nebraska is the number 2 producer of corn in the US. Thanks to irrigation. Also, Oklahoma, Kansas, South Dakota and North Dakota have been major wheat producers for over 80 years.

And for major cities in Florida with temperature records going back to the late 1800s, most of the record highs are still from the late 1920s, the 1930s and the early 1940s. While the cities with records only going back some approximate 75 years, manage a fair number of new highs in more recent years. What is going into the records now is at least questionable to me. For example, here not far South of downtown Orlando, FL, I experienced this February 3 straight days of freezing weathers, with Temperatures of 30, 31 and 32-degrees. This killed part of my fall garden planting and damaging a number of fruit trees in the neighborhood. Now if I look at past whether history for these same days the lowest temperature is said to be 36 degrees.

I believe I remember reading that the IPPC has to exclude the 1930s to make their forecast of increasing temperature projections work. Maybe this is correct use of Statistics, but in my use of Trends to forecast future events, I tried to use as much good history as I could obtain and used Regression to project the likely future events. Maybe it is different this time and we need to forget everything but the more recent past. However, if this were so why isn’t it being explained by those most certain about future temperatures.