Five Questions the Senate Should Ask President Biden's White House Science Office Nominee

Dr. Eric Lander of MIT will testify at a confirmation hearing on Thursday for the role of Director of the White House Office of Science and Technology Policy

Later this week, the Senate Committee on Commerce, Science, and Transportation will hold a hearing to consider the nomination of Dr. Eric Lander of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology to serve as the director of the White House Office of Science and Technology Policy. Below are five questions that I recommend be asked of Dr. Lander.

Before getting to the questions, however, let me first explain OSTP and the important parallel role that Lander will play in the White House. OSTP was established by Congress in 1976, after President Richard Nixon had earlier axed its predecessor, apparently in a fit of rage over student protests against the Vietnam War at MIT and elsewhere. Congress wanted to ensure that science and technology played an important, permanent role in the Executive Office of the President, and thus established the office by statute and required Senate confirmation of its director, who was to be appointed by the president.

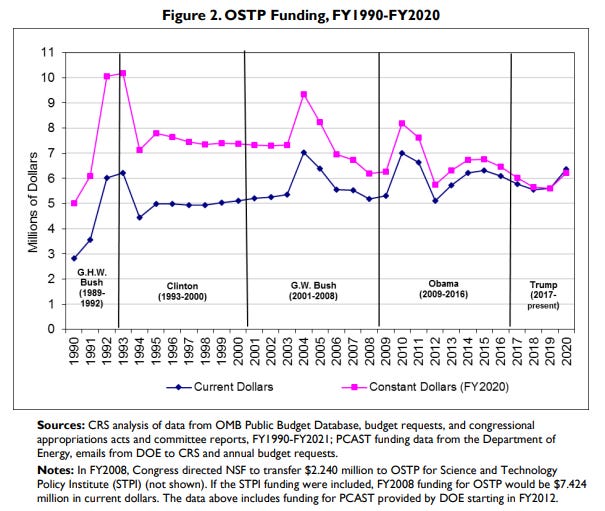

The OSTP director has typically (but not always) worn a second hat — Assistant to the President for Science and Technology. It is this position that actually confers the formal title of “science advisor” to the president but whether or not the OSTP director actually carries the “special assistant” title, he (and so far it has always be a he) has always colloquially been referred to as the president’ science advisor. In recent presidencies, neither Kelvin Droegemeier (Trump) nor John Marburger (GHW Bush) carried the titled of “special advisor” but John Holdren (Obama) was given that role. The figure below shows OSTP funding under the past five administrations (via Congressional Research Service).

The ability of a science advisor to serve as a close confidant of the president is somewhat hampered by the dual roles. A “special assistant” might be expected to offer political as well as policy advice to the president in closely-held settings protected by executive privilege. However, as the OSTP director is also required to testify before Congress, there may be limits to this privilege — though it has never really been tested. This concern might help to explain why, in recent decades, the science advisor has never been among those in the trusted, close inner circle of presidential advisors.

President Biden has indicated that Lander will be a member of his cabinet, the first time the OSTP director will have played such an elevated role. While it remains to be seen if Lander will become “the most powerful scientist in U.S. history,” the increased stature of his role and the central importance of science and technology policies to a wide range of U.S. policies should mean that he faces some important questions — from both Democrats and Republicans — at his confirmation hearing later this week.

Here are five questions that I think he should be asked.

On January 20, 2021 President Biden gave Lander a mandate to undertake a major study of five questions in order to “make recommendations to our administration on the general strategies, specific actions, and new structures that the federal government should adopt.” These questions are:

What can we learn from the pandemic about what is possible—or what ought to be possible—to address the widest range of needs related to our public health?

How can breakthroughs in science and technology create powerful new solutions to address climate change—propelling market-driven change, jump-starting economic growth, improving health, and growing jobs, especially in communities that have been left behind?

How can the United States ensure that it is the world leader in the technologies and industries of the future that will be critical to our economic prosperity and national security, especially in competition with China?

How can we guarantee that the fruits of science and technology are fully shared across America and among all Americans?

How can we ensure the long-term health of science and technology in our nation?

These are important, well-crafted questions, the answers to which and recommendations that follow could have potentially transformative implications for policy making across government.

What process has OSTP put into place to answer them? How is OSTP ensuring that participation is inclusive? How will the recommendations be connected to administration and Congressional policy making? Ultimately, is this just “busy work” (which we can mostly ignore) or does it actually have political standing (which would make it important)?

When will the administration be working with Congress to propose scientific integrity legislation to complete the task of ensuring “the highest level of integrity in all aspects of executive branch involvement with scientific and technological processes”?

On January 27, 2021 President Biden issued a memorandum on science integrity that established a task force to review scientific integrity policies across the federal government. That task force has 30 days left before their report is due. After delivery of the report the Biden administration promises that in another 120 days (so, the last week in September, 2021) it will “develop a framework to inform and support the regular assessment and iterative improvement of agency scientific-integrity policies and practices” and post that framework on its website.

While the development of a framework may be worthwhile, we learned during the Obama and Trump administrations that enforcing scientific integrity guidelines consistently and effectively across government will require more than administrative memos and guidelines. Legislation is needed and has been proposed, including that by Rep. Paul Tonko (D-NY), who wrote in a January letter to President Biden, “we encourage your administration to work with us i Congress to pass and implement the Scientific Integrity Act, practical bipartisan legislation passed on several occasions by the House.”

Will the Biden Administration support this legislation? If not, why not?

What procedures does OSTP have in place to ensure that scientific integrity standards apply to its work and that in other agencies where science and other expert advice is procured?

Recently, a career scientist from USGS was removed from her position overseeing the national climate assessment by OSTP, according The Washington Post, because she may have been “unpopular with Biden administration officials who wish to present an unnuanced portrayal of the threat of climate change.” How is this any different than when the Trump Administration removed an earlier career scientist leading the NCA? Should expert advisory bodies be headquartered within the Executive Office of the President, making such political tinkering almost inevitable?

Similarly, the Michael Regan, a political appointee and director of the Environmental Protection Agency recently fired dozens of external science advisors on its Science Advisory Board and the Clean Air Scientific Advisory Committee. And this is not a unique event — entire expert advisory boards have also been purged in the Department of Homeland Security and the Department of Defense.

Should expert advisory boards be routinely disbanded and then politically appointed by each administration? Should we now expect that each new president will pick their administration’s advisors following each election? What will OSTP do to ensure that advisory mechanisms are independent and not empaneled based on actual or perceived friendliness to the administration’s political agenda?

What is the Biden Administration’s position on current debates over the future of the National Science Foundation and, in particular, the respective roles of “basic research” and industrial policies across the U.S. R&D landscape?

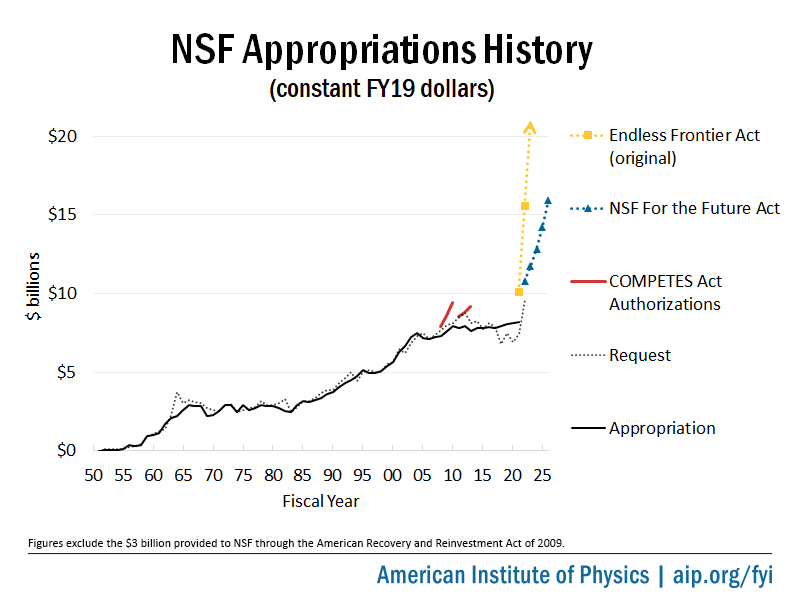

The budgetary scale of the proposed changes to the National Science Foundation can be seen in the figure below, from the American Institute of Physics.

Senators from both parties have expressed some concerns about re-orienting federal research toward supporting specific technologies. For instance, Senator Maria Cantwell (D-WA) expressed concerns, “I want to make sure that we continue to think of ourselves as a capitalist country in how there's nothing better to put the right money on the right research than when capital is on the line.” Senator Roger Wicker (R-MS) expressed related concerns, “Strategic investments in technologies and supply chains are important, but we will not win by simply throwing money at the problem.”

What is the Biden Administration’s position on U.S. industrial policy? Doesn’t the U.S. have an emerging industrial policy under President Biden — such as reflected in last week’s greenhouse gas reduction target? Should the administration outline a comprehensive approach to industrial policy, from which proposed, significant changes to NSF and other federal R&D agencies can be evaluated in broader policy context?

What will the Biden administration do to ensure — in deeds not just words — that post-secondary education of all forms becomes more accessible to more people?

This includes professional, university and other forms of training and education that have traditionally been out of reach to many due to costs and structural factors that create barriers to entry. For instance, a 2020 report of the Education Trust found that at 101 of the nation’s most “prestigious and best-funded public colleges enroll a smaller percentage of Black students today than they did 20 years ago, and while the numbers of Latino students on these campuses has increased, Latino enrollment is not keeping pace with the Latino population growth in most states.”

During the campaign candidate Biden promised, among other things, to:

Make public colleges and universities tuition-free for all families with incomes below $125,000;

Double the maximum value of Pell grants, significantly increasing the number of middle-class Americans who can participate in the program;

More than halve payments on undergraduate federal student loans by simplifying and increasing the generosity of today’s income-based repayment program;

Create a “Title I for postsecondary education” to help students at under-resourced four-year schools complete their degrees;

Providing two years of community college or other high-quality training program without debt for any hard-working individual looking to learn and improve their skills to keep up with the changing nature of work;

What is the role of OSTP in helping to expand access to post-secondary educational opportunities necessary to develop a work force capable of taking on the Biden Administration’s industrial policy commitments while achieving greater equity and accessibility to educational opportunities? How will the nation’s public universities, many funded in large part by high tuition often based on student debt, need to change to adapt to these profound changes? What does success look like over the next three years?

There are of course many other questions that should be presented to Lander — involving the pandemic response, the lessons learned from it, international scientific collaboration, the space program, American competitiveness, regulation of research with potential military applications or public health consequences, investments in agricultural research, support of the R&D necessary to achieve climate policy targets and on and on. Science and technology policy today has connections to just about every aspect of federal policy making.

OSTP has for decades served as an important, if behind-the-scenes, agency primarily focused on the crucial but thankless job of creating an integrated perspective of research and development in the federal government. It has mainly approached this task through the lens of the the federal budget and in partnership with the Office of Management and Budget. Today, with Lander being seated in President Biden’s cabinet and given an initial portfolio with topics ranging from reviewing the pandemic response to climate change to competitiveness with China, it may be that OSTP is preparing to assume a greater role in administration policy proposals, oversight and implementation. If so, it is imperative that Congress makes sure that the president’s nominee and OSTP more generally are up to the task.