Five Challenges Facing Science Communication

A quick summary of my keynote lecture today in Copenhagen

Today I had a great opportunity to speak at the the closing workshop of the EU-funded cross-cutting activity on science communication of its Collaboration in Science and Technology, held in Copenhagen. My talk was wide-ranging and reviewed some recent work we’ve done under the EScAPE program on science advice in the pandemic. In this post, I summarize five big challenges that I see for “science communication” — a concept and area of practice and inquiry that is not always so well defined.

Here is a picture of me speaking today, a bit jet-lagged after waking up early and watching the Colorado Avalanche in the Stanley Cup Final.

Challenge #1: How do we make music not noise?

I have always thought that the notion of “science communication” carries within in it an inherent, unreconcilable paradox. I illustrated that in my talk today with an analogy: Imagine, I asked the audience, that each of you have a musical instrument that you are able to play with various levels of proficiency, from seeing it to the first time to internationally accomplished musicians. Then I ask you each to “communicate” your music. What would then be the result? Noise.

Science communication finds itself in a similar situation. We ask scientists, and especially young scientists, to communicate their work — get a blog, record a podcast, write an op-ed, speak with elected officials and more! If everyone does this, and succeeds, the result will be noise. One big challenge for science communication is to develop mechanisms that produce music, not noise, just as a symphony does.

It was interesting to hear conference participants run with the music metaphor throughout the day and to discuss what it might imply, where it is helpful and where it is not. For me, the metaphor points to the need for coordinated, institutionalized approaches to the integration of science and expertise with the public and policy makers.

Challenge #2: Science communication has a dark side

As I opened my talk, I explained how my views on science communication have been shaped by my experiences. I briefly related one anecdote in particular — Almost a decade ago I achieved great success in communicating science by any conventional metric, seeing my nerdy Congressional testimony receive 400,000+ YouTube views. I presented well-established, peer-reviewed consensus climate science, only to find myself subsequently attacked by the White House and investigated by the U.S. Congress, abandoned by my university, ultimately turning my career upside down.

I won’t go into the details here — you can read this post for those — but I will observe that we need to better prepare scientists for what it might mean to “succeed” in science communication. As an old American aphorism goes, politics ain’t beanbag.

Challenge #3: “Shadow science advice” can make policy work better, or make it worse. We should know the difference.

One important finding of our research on science advice in the pandemic has been to document the importance of what we call “shadow science advice",” defined as:

Formal or informal mechanisms of advice established outside of governmental science advisory processes to provide a counter or opposition body of legitimate, authoritative and credible guidance to policy makers.

Groups such as the Independent SAGE in the UK and the authors of the Great Barrington Declaration offer examples of shadow science advice, which is as endemic as COVID itself. In my talk today I also characterized the many instances of shadow science advice seen in the pandemic as incredibly successful examples of science communication — if success means experts taking their views public and reaching a broad audience — but of questionable value in democratic policy making and politics.

Obviously the “success” of shadow science advice needs to be evaluated more broadly than just in terms of communication. I have argued that in many countries, shadow science advice actually compromised the challenge of effectively connecting expertise and decision making, and in some cases made things much worse. We need to know the difference.

Challenge #4: The deficit model always lurks

There was a lot of talk today of the so-called “deficit model” of science communication — in a nutshell, the idea that educating people about the substance or process of science will lead those people to then adopt the “right” views on policy and politics. Those present today at the conference are well aware of the deficit model and its problems.

But not everyone who engages in “science communication” is so cognizant of the theory and experience that informs us of the limitations of a deficit model approach. For instance, providing people with scientific information about an approaching tornado may be sufficient to motivate the “right’ action — shelter! But providing people with scientific information about the benefits of vaccination many not motivate the “right” action — vaccinate!

Those of use working where expertise meets decisions need to understand where the deficit model works, where it does not, as well as its potential, if misapplied, to make things worse. Sometimes that means that science communicators are working at cross purposes.

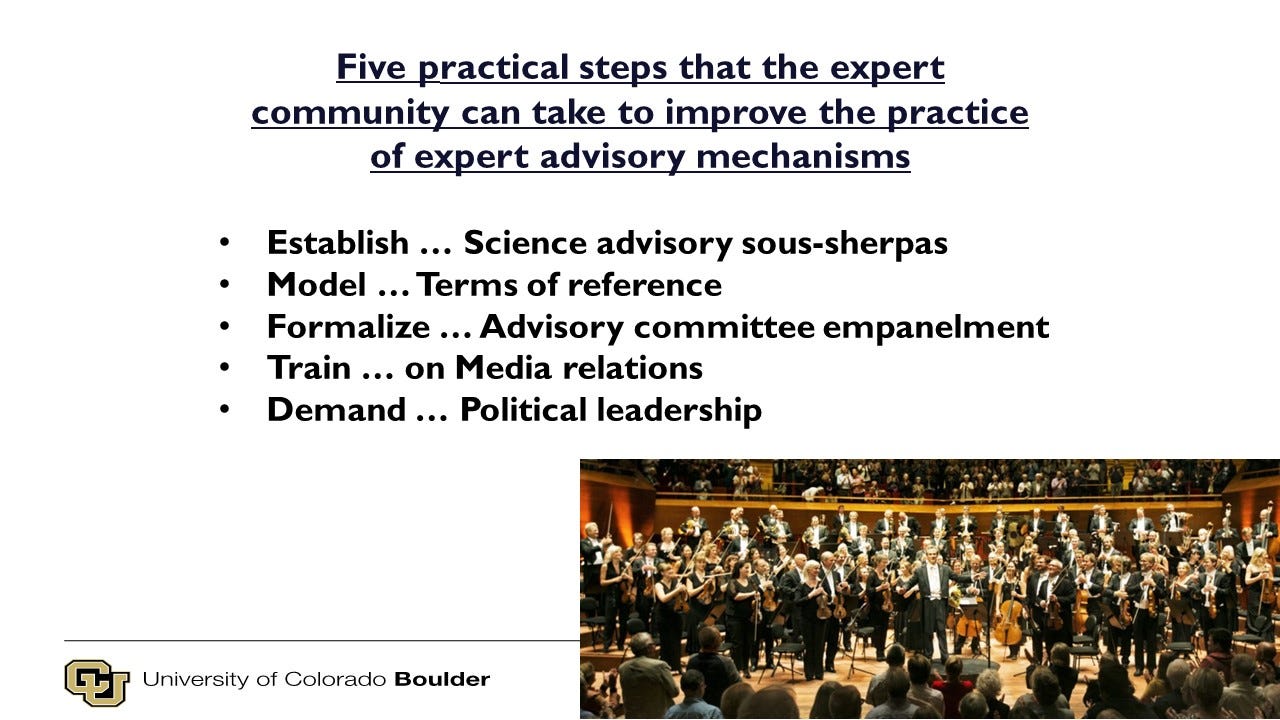

Challenge #5: Institutions mater most for effective science communication

I closed my talk today by recommending some practical steps that those involved in science communication on highly politicized topics might take to over come the challenges discussed here, and to improve the connections of expertise and decision making in democratic systems. These are listed in the slide below.

A quick summary:

Science advisory mechanisms might learn from the practice of diplomacy. “Sherpas” are those who represent decision makers, paving the way for diplomacy to work. Diplomatic “sous-sherpas” are those even further behind the scenes, with the expertise and experience necessary to give diplomacy the best chance possible to work. Science advice needs institutionalized sous-sherpas.

“Terms of reference” refer to the formalized expectations put on paper for the scope and functions of an expert advisory body. We have learned in the pandemic that science advisory mechanisms in many places around the world were often ad hoc and improvised. We have sufficient experience in formal science advice that we should be able to provide model terms of reference for a wide range of different types of science advisory mechanisms.

Who gets to sit on formal science advisory committees and participate in science advisory mechanisms often emerges from a black box. Such processes should be opened up, made more transparent and better connected with the terms of reference guiding the work of expert advisors. Here as well, we have a lot of experience to draw upon.

Experts who serve in formal roles and as shadow science advisors would often benefit from greater training on media relations. One part of this would involve the mechanics of communicating with the media, but another crucial part would include discussions of ethics and responsibilities of experts in democratic systems of governance.

Finally, all of us in the expert community should demand leadership — both among politicians to respect the legitimacy and diversity of expert advisory mechanisms even (or especially) when the advice given is uncomfortable. but also from leaders of the scientific community, to recognize that advice comes in many forms beyond political advocacy.

Many thanks to David Budtz Pedersen, Professor of Science Communication, Aalborg University Copenhagen, COST CCA Chair and to Judith Litjens, Policy Officer at the EU COST Association.

Paying subscribers to The Honest Broker receive posts with pointers to recommended readings, occasional direct emails with PDFs of my books and paywalled writings and the opportunity to participate in conversations on the site. I am also looking for ways to add value to those who see fit to support my work.

There are three subscription models:

1. The annual subscription: $80 annually

2. The standard monthly subscription: $8 monthly - which gives you a bit more flexibility.

3. Founders club: $500 annually, or another amount at your discretion - for those who have the ability or interest to support my work at a higher level.