This is a guest post by Iddo Wernick of Rockefeller University, discussing his fantastic new paper:

IK Wernick. 2025. Is America dematerializing? Trends and tradeoffs in historic demand for one hundred commodities in the United States. Resources Policy vol. 101, February.

For over three decades, Iddo Wernick has worked on measuring and analyzing how technology systems influence societal resource consumption and the natural environment. He continues to conduct research at the Program for the Human Environment at Rockefeller University where he began working in 1992. Current he is also a senior fellow at the National Center for Energy Analytics and The Breakthrough Institute.

I’m thrilled to share Iddo’s work with the THB community. —RP

Counting Materials

People crave a bite-sized summary of the functioning of an elaborate system. In the 1930s the entire US economy was summarized into a new measure called Gross Domestic Product (GDP). Since the energy crises of the 1970s, Americans have also carefully measured the energy they produce and consume in attempts to create summary indicators.

In the decades since, environmental concerns fueled this activity as energy studies have proliferated. These analyses aimed to show trends in the performance of the energy sector and reveal pathways for the economy to become more energy efficient and less vulnerable to foreign actors.

Initially the fear was the depletion hydrocarbons as predictions of Peak Oil supply occurring between 1965 and 1970 seemed to be coming true. By the 1980s, concerns shifted to a byproduct of hydrocarbon combustion — carbon dioxide — and its influence on the global carbon cycle and climate.

As climate and energy have become essentially synonymous in our daily lexicon, climate studies have become replete with analyses of energy production. The abundance of energy analyses available today may not lead to simple conclusions, but governments can rely on the extensive efforts that have gone to measuring how society consumes energy and how that consumption might impact the natural environment.

What about materials? What about the physical resources used to construct our homes? Build roads, ports, airports, and vehicles? Distribute fuels and provide constant electric power? What about all of the materials used to construct and support the telecom cables and the data centers that support modern industrial societies?

Certainly, the vast increase in the use of materials in industrial societies also threatens environmental quality and ought to be measured. Just like GDP is supposed to encapsulate the economy and gigatons of carbon dioxide are used to describe the threat to the climate, some overall measure should indicate where we are and where we are headed in terms of materials use.

Can we measure how much material society uses? Can we capture the environmental impact of the materials society uses?

Such measures would find broad interest and offer governments a more comprehensive quantitative basis for decisions on natural resources policy. Traditional environmentalists could use the data to support claims of surging demand for commodities and its impact on the planet. At the same time, technology advocates could use the data to emphasize that economic growth has decoupled from material consumption, a process they call dematerialization.

Simply adding the mass of all the materials that society uses would seem to offer an obvious choice for measuring materials use. But while kilograms offer a common and understandable denominator for measuring materials from cadmium to cotton, they fail to capture the impacts that make materials environmentally meaningful.

Established sets of indicators describe the environmental impacts of social material use considering things such as resource depletion, emissions to air, water and land, and even ecosystem disruption. The framework for environmental accounting differs from those for financial accounting as it relies on multiple estimates and averages in calculating materials flows. Furthermore, unlike the case for money, the accounting results do not reduce to any single currency for environmental outcomes.

To address the difficulties inherent in measuring how materials use impacts the natural environment, analysts have pursued the option of aggregating the kilograms into environmentally relevant categories that describe social material use in order to observe trends in national performance. A key aim of this effort is to create an environmental analog to GDP that enables government bureaucracies to replace Euros and Dollars with kilograms to allow for integrate material flow data with national economic accounts and offer a sound basis for environmental policies.

As a result of the broad implementation of national level indicators based on material flows in the nations of the European Union and Japan, researchers have refined the accounting methods for national materials accounts. The effort has served to document the decoupling of economic growth and measures of material consumption. The EU Material flow analysis has also successfully documented the fact that much of the environmental impact from consumption in these countries can be found in resource rich countries far away.

I have been working on the problem of tracking societal materials use for over thirty years. Unquestionably, the methods for material flow accounting have improved over the decades. However, despite their implementation in national policy frameworks they remain obscure and self-referential. The complexity of the actual material world leads analysts to generate accounting systems that become more elaborate and more intricate at the same time.

In a recent paper I take a different approach in attempting to answer the question of whether industrial societies are undergoing dematerialization using the United States as an example.

Because the universe of materials is so vast, answering the question depends on which ones you look at. In an attempt to cover the range of materials used by society, this study documents demand for 100 commodities that comprise the vast bulk of material flows in the US, dividing them into three groups based on whether and how they dematerialized between the years 1970 and 2020.

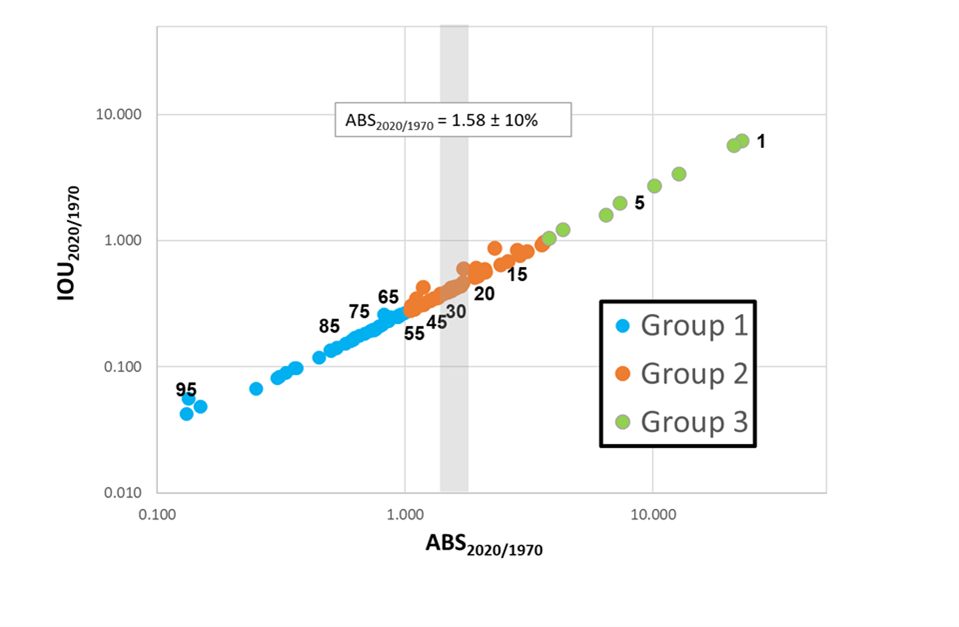

In the figure below, the X-axis denotes the ratio of absolute consumption of a commodity for the years 2020 and 1970 — ABS. The Y-axis denotes the same quantity divided by the annual GDP — the intensity of use or IOU.

The numbers in the plot correspond to the 100 different commodities (for a full numbered list see Table 2 in the paper).

The gray bar down the center represents constant per capita consumption ±10%.

Of the 100 commodities on the plot the 41 blue dots — including iron ore, arsenic, and sodium sulfate — dematerialized in absolute terms and relative to the economy as a result of the diffusion of technology, changes in regulations, and markets trends.

For the 51 orange dots — including staples like petroleum, cement, beef, paper, and fertilizers — commodity consumption decoupled from economic growth but grew in absolute terms in line with increases in population.

Finally, for the 8 green dots, demand rose faster than economic growth — including high-tech metals like titanium and indium, and the high-tech protein, chicken.

Is America truly using less material?

The decoupling of demand and economic growth for the majority of commodities suggests increasing efficiency in how materials are used in the US economy. Some herald this result as indicating that future economic growth need not mean more material use not only at home, but also globally.

Others focus on the fact that as services dominate the American economy, production has shifted offshore for many commodities. For critical materials like lithium and rare earths, US consumption today comes primarily in the form of products manufactured in other countries.

But can offshoring persist indefinitely? Can materials processors continue to find access to untapped resources with ever lower costs for labor and environmental compliance?

Analysts are getting better at encompassing the scope and complexity of the material flows that underly modern industrial economies, but the results from the United States are mixed.

Greater efficiency allows the rate of economic growth to outpace the reliance of physical materials, but as the economy expands it still absorbs more material, it just does so more efficiently. Also, as services have come to dominate the national economy, much heavy production has moved offshore and the importance of a functioning physical infrastructure has only grown.

Experience with advanced economies shows that wholesale improvements in material efficiency are possible and desirable for the future. The challenges ahead lie in reducing the environmental impacts of both the more benign high volume material flows as well as the more toxic low volume material flows that support the industrial societies we live in and the standard of living that Americans enjoy.

For the rest of the globe, industrial development will happen. As the standard of living rises around the globe demand for materials will rise. We cannot eliminate the material flows that support modern industrial societies and should not aspire to, but we can take the lessons of the past to better manage them and integrate them with the natural environment.

Read Iddo’s full paper: Wernick, I. K. (2025). Is America dematerializing? Trends and tradeoffs in historic demand for one hundred commodities in the United States. Resources Policy, 101, 105463.

Learn more about Iddo and his research here.

Comments welcomed!

The easiest thing you can do to support THB is to click that “♡ Like”. More likes mean that THB gets in front of more readers!

Iddo just shared with me this paper of his, clearly showing that we are of the same generation!

https://phe.rockefeller.edu/docs/Wernick%20IS&T%20Winter%202014.pdf

Just a note on presentation; for those among us who happen to be color-blind (including me, sadly) those squiggly graphs with the subtle color differences approach unreadability. For maximum clarity, it is nice to have graphs with points marked by exes, ohs, triangles, squares etc.