Climate Policy is Happening, Climate Science Needs to Keep Up

A new report today in advance of COP-26 shares good news on policy, with profound implications for climate research

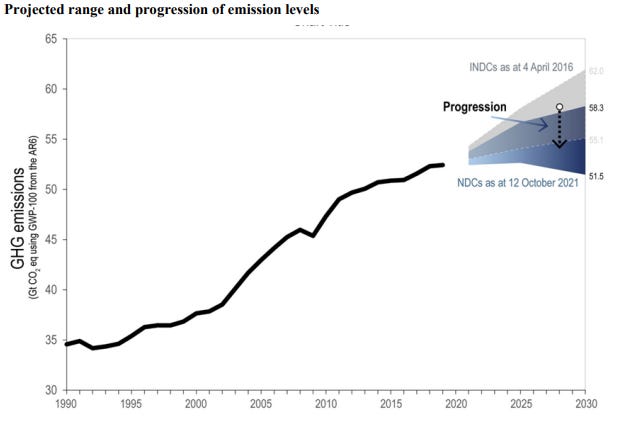

Sometime in the not-too-distant future, when we look back at how we solved climate change, there is a good chance that 2016 will be looked at as the year when our expectations for our collective climate future hit rock bottom. That year, under the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (FCCC), whose 26th Conference of Parties starts this week in Glasgow, expectations were that by 2030 global emissions of greenhouse gases could reach 62 gigatons (CO2-eq). Things looked pretty grim.

But in the five years since, it is absolutely incredible how quickly expectations have changed for the better. In its latest update, the FCCC reports that by global emissions of greenhouse gases in 2030 could be as low as 51.5 GtCO2, a 17% reduction in expectations in just five years. You can see this in the figure below from this year’s FCCC report. Of course, the only things guaranteed in life are death and taxes, but the change of expectations in such a short time is perhaps the most remarkable aspect of climate policy that almost no one is talking about. It is even possible that global emissions have or will soon peak.

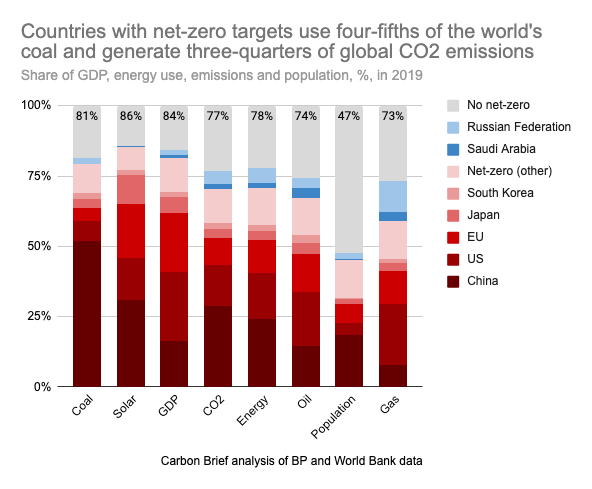

The incredible shift in expectations has stunned even close observers. Dr. Simon Evans of Carbon Brief observes that today, “more than three-quarters of global CO2 emissions are covered by net-zero pledges.” He says of the chart of net-zero commitments shown in the Tweet below, “I would never have believed you if, at COP21 [in 2015], you'd told me I would be making this chart today.”

Believe it. We are in a new world.

What happened? Two things.

First, the real world has changed much faster than anticipated. Technological and economic progress in energy technologies such as wind and solar has advanced much faster than many expected. In parallel, and even less foreseen, the global reliance on coal energy has changed dramatically, with rapid decreasing reliance on coal and commitments to coal, even as China and India (in particular) continue to rely heavily on the dirty fuel. But even in those countries, coal’s future appears limited. Of course, replacing coal with natural gas would dramatically reduce carbon dioxide emissions in the short term, but to achieve net-zero targets, eventually emissions from gas will also have to be eliminated. Achieving net-zero carbon dioxide remains a massive challenge.

Second, our imagined world also has changed much faster than expected. In particular, we now know that our collective earlier expectations for future emissions growth were overly pessimistic. For instance, the near-term emissions scenarios of the International Energy Agency have in recent years been successively revised down, even before the COVID-19 pandemic. More generally, the scenarios that underlie much of the work of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change and the research that it assesses are grossly out-of-date. In particular, across the board they depend on a core assumption of increased coal consumption through the rest of the 21st century. That’s not going to happen.

This latter point should force a rethink of the current prioritization of studies in climate research, which lean heavily on these out-of-date scenarios. Consider that the top priorities for climate research in climate modeling emphasize the extreme scenarios in blue in the figure below. But in contract, the expectations of the FCCC released today (in red) are much closer to the middle scenario in black.

It was just three years ago that the US National Climate Assessment characterized that middle black scenario as representing climate policy success. According to the UN FCCC and the IEA, the world is presently on track to undercut that scenario to 2100 (but please remember the admonition about death and taxes). Today, that middle-black scenario might be more properly called a high-end scenario – representing what happens if current commitments are not met or even reversed — rather than a scenario of climate policy success.

Some leaders in the scientific community have apparently had a hard time accepting that the world has changed. Writing this week in Issues in Science and Technology of the US National Academy of Sciences, its president and a former co-chair of the IPCC’s Working Group 2 argue inexplicably of the most extreme scenario (the most extreme scenario in blue above — SSP5-8.5):

[T]he high-emissions RCP8.5 scenario has long been described as a “business-as-usual” pathway with a continued emphasis on energy from fossil fuels with no climate policies in place. This remains 100% accurate, even if RCP8.5 does not appear to be the most likely high-emissions pathway.

Similarly, the lead author responsible for assessing scenarios in the most recent US National Climate Assessment also asserts (strangely, given the evidence) that the world remains on the highest trajectory of emissions among the five scenarios shown above. Of course these claims are easily shown to be incorrect (just look at the figure above or our recent analysis).

The good news for climate policy means that climate research needs to be newly nimble to keep up. Specifically, that means there is a pressing need to abandon out-of-date scenarios and to create new ones that are fit for purpose in 2021. Make no mistake, this will be incredibly difficult given the huge institutional momentum built up behind the out-of-date scenarios. Centering out-of-date scenarios in climate research to inform climate policy is a lot like driving your car down the highway looking in the rearview mirror — as impressive as it may be, it is unlikely to get you to your destination.

In the jargon of technical acronyms, the climate community needs to immediately leave behind the RCPs and SSPs, and to commit to a crash course to develop new, policy-relevant scenarios to guide policy from where the world is in 2021. This will be tough medicine to swallow, given the enormous academic and economic industry that has developed around these scenarios.

More generally, given how fast the world is evolving, it is important to develop a capacity to generate quickly policy-relevant knowledge in support of climate policy on a time scale of months rather than years. This likely will require distinguishing climate science research that is pursued for its intrinsic interests among climate researchers from that which is timely and useful in policy discussions (even as there is some overlap). We have been here before.

Climate science policy — how we make decisions with and about climate science — is newly relevant. And that is good news, because it means that climate policy is moving and the scientific community needs to be ready to keep up. But the new context also means that climate research, or at least some significant part of it, needs to refocus its priorities on the information needs of policy makers.

I think Roger was on a "Rocky Mountain High" when he wrote this all but unintelligible article.

The link to the "new FCCC report" goes to a "page not found" display.