Chromosome Sex Testing is Back!

All elite female swimmers must undergo sex testing under new regulations out today

In 2005 the head of the International Olympic Committee’s (IOC) Medical Commission wrote of chromosome sex testing of women, “genetic screening for female gender in sport is history, saving a lot of embarrassment—and money.” The IOC decided to abandon chromosome testing for good reasons — it didn’t work, was a public relations nightmare and female athletes objected.

So it is surprising that FINA (Fédération Internationale de Natation) — the Olympic sport body that oversees swimming — announced a new policy today regulating gender eligibility in its events that mandates sex testing for all female athletes. The new FINA policy has received a lot of attention for its effective ban on the participation of transgender women in women’s competition. I’ll have more to say on the ban in the future, but today I’d like to focus on the policy’s requirement that “All athletes must certify their chromosomal sex with their Member Federation in order to be eligible for FINA competitions.”

Under an overly simplistic and wrongheaded view of human biology, chromosome testing might seem like it makes sense as a way to distinguish men from women. Such wrongheadedness led sports officials more than 50 years ago to adopt chromosome testing as an eligibility screen for elite female athletes. After all, if human biology is as simple as XX = female and XY = male, then a chromosome test would seem like an appropriate tool to distinguish women from men. Human biology is not so simple. As the WHO has explained, “clearly, there are not only females who are XX and males who are XY, but rather, there is a range of chromosome complements, hormone balances, and phenotypic variations that determine sex.”

FINA could have focused its new regulations exclusively on transgender individuals, those with a gender identity different than that at birth. Instead, FINA chose to center its regulations on all individuals with XY chromosomes. But in reality biology is complicated — for instance, there are XX males and XY females, and other complexities as well — none are common, but they do exist, and they do participate in sport. This complexity is one reason why chromosome testing was abandoned by sports organizations a generation ago.

Elite sport learned of the problems with chromosome testing after its sex tests revealed women with variations of sex development, but who were nonetheless women. According to official data from track and field, across competitions from 1972 to 1990, one in 504 female athletes “failed” the organization’s sex test. Such failures were embarrassing for sport and stigmatizing for the affected women, some of whom were “erroneously excluded” from participation. In the 1996 Summer Olympics in Atlanta, 8 of 3,387 female athletes “failed” the IOC sex test, but all were eventually allowed to compete — because they were women. Soon after chromosomal sex testing was abandoned.

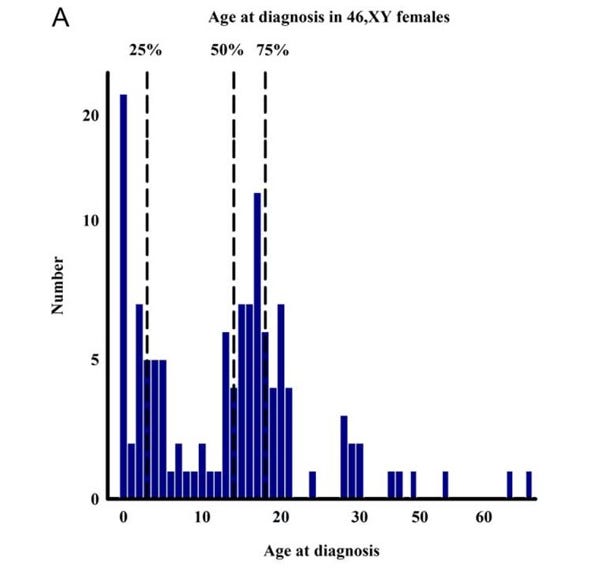

More recent research backs up the data from track and field: A Danish study found a “prevalence of 46,XY females was 6.4 per 100,000 live born females.” If FINA goes looking for XY females, they will no doubt find them.

The Danish study also found that ~25% of 46 XY females learned of that fact when they were 18 or older (as shown in the figure above). That means, inevitably, some of FINA’s athletes will learn of their variation in sex development from FINA’s sex test, as they would have been previously unaware. According to FINA’s policy, any athlete that “fails” their sex test (or is otherwise suspected of having XY chromosomes) must submit to a physical examination by an “independent expert” who is not their physician. Invasive physical exams to assure sufficient womanliness should not be a requirement to participate in elite sport.

The fact that chromosome testing failed to accurately identify who was and was not a women for purposes of inclusion in women’s sport categories and the invasive consequences for women caught by the test are reasons why the practice was determined to be “both inaccurate and discriminatory.” Now it’s back.

We don’t yet know why FINA decided to pursue regulations focused expansively on chromosomal make-up, rather than narrowly on transgender athletes. However, we do know that FINA has taken a major step backwards by adopting policies that will affect all female athletes and cause unnecessary harm to some of them. Perhaps the new FINA regulations are a Potemkin policy — designed to scare off certain women from even trying to compete in the first place, and thus not needing actual implementation.

The issue of sex testing is not about trans athletes but about cisgender athletes competing in their gender category from birth. It does appear however that the panic over trans athletes has led many organizations — FINA now as well — to adopt policies that are unnecessary, harmful and sure to cause many problems in the future. I suspect that the new FINA policy will have its day in court. Watch this space.