"Billion Dollar Disasters" are a National Embarrassment

You won't find a more obvious example of bad science from the U.S. government

Eleven years ago this week, I wrote my first critique of the so-called “billion-dollar disaster” count promoted by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA). The dataset and how it is used represents one of the most spectacular abuses of science you will ever see — and obviously so, it is not even close. Yet, the U.S. government and big media outlets continue to promote the dataset, while experts who know better stand by silently.

The “billion dollar disaster” meme offers a wonderful example of what progressive activist and film maker David Sirota (DON’T LOOK UP) calls “the algorithm” which he explains as:

An information ecosystem in which news outlets promote or suppress facts based on whether those facts will flatter or offend their audience’s partisan impulses. . . Stories that might shame Democrats are amplified by right-wing media, but effectively shadowbanned by legacy and left-of-center media that do not want to offend a liberal readership that loathes news that might shame the Democratic politicians they worship. . . It’s the same thing on the other side.

What is the “billion dollar disaster” dataset?

NOAA counts the number of disasters in the United States that result in losses of greater than $1 billion and promotes the results a few times every year, generating headlines. The dataset is compelling clickbait because over the past three decades the count has shown a sharp increase, from five or less such disasters each year in the decade of the 1980s to fifteen or more in each of the past 3 years.

That increase in the number of economic losses over the $1 billion threshold is routinely cited as conclusive evidence of changes in extreme weather that are the result of climate change, such by President Biden (emphasis added):

Climate change is a major driver for the increased frequency, duration, and severity of extreme weather and climate-related disasters. Millions of Americans feel the effects of these extreme events when their roads and schools flood, and hospitals lose power. Over the past few years, the frequency of extreme weather and climate-related disaster events with losses exceeding $1 billion has skyrocketed. From 2000 to 2009, these billion-dollar disasters occurred 6 times a year on average. From 2010 to 2020, that number increased to an average of 13 events per year, causing more than $975 billion in disaster damages over the decade.

The “billion dollar disaster” meme is more than just clickbait — beyond the White House, it has made its way into the reports of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, the U.S. National Climate Assessment and into various U.S. regulatory and legislative policies.

But wait a second — isn’t it great that NOAA science is making its way to the public, into federal policy, and all the way to the President? Actually, no. The billion-dollar disaster tally is easy to understand, simple to communicate, but in actual fact, incredibly misleading. It is climate misinformation.

Before proceeding, let me emphasize that climate change resulting from the burning of fossil fuels poses significant risks to our collective futures, including influences on extreme events. As a consequence, it makes sense to focus policy on the mitigation of emissions and adaptation to reduce vulnerability and exposure to weather and climate. But the importance of climate change as a policy issue does not mean that any claim related to climate gets a free pass when it comes to upholding standards of scientific accuracy and integrity, and especially claims made by (what should be) authoritative bodies like NOAA.

The billion-dollar disaster tally, even though it is popular, doesn’t come remotely close to meeting that standard. Let’s take a quick look at some of the details which easily show the fatal flaws in the dataset.

Back in 2012, when NOAA first released the billion-dollar disaster dataset, I observed that it neglected historical events that, after considering inflation, would have exceeded the billion-dollar threshold. For example, a disaster that caused $900 million in losses in 1980 (in 1980 dollars) would not have been included, although the inflation-adjusted loss amount would have exceeded $1 billion in contemporary times.

After this was pointed out, The Washington Post took note of the obvious problem and subsequently, NOAA included inflation and as a result added some earlier events to their dataset. At the time, NOAA also added a warning about interpreting the dataset:

“Caution should be used in interpreting any trends based on this graphic for a variety of reasons.”

That warning has long since disappeared and The Washington Post now breathlessly promotes the flawed dataset.

One big problem with the use of the billion-dollar threshold: U.S. disasters take place at the intersection of a changing and variable climate and a nation growing in population, wealth and development. Consider that an identical hurricane making landfall in Florida in 1980 versus 2023 would result in vastly different loss totals, because today there are simply more people in more homes with more stuff than 43 years ago.

For instance, in 2012, taking into account societal changes I identified nine disasters from 1980 alone that were not included in the NOAA tabulation that would have exceeded a billion-dollar threshold in 2012 had those events occurred with contemporary levels of economic development. You can learn more about the importance of considering societal change alongside climate change for understanding disasters in my series on “making sense of trends in disaster losses.”

The NOAA billion-dollar disaster dataset is not a reliable indicator of trends in disasters or their costs, and it certainly is not a time series that says anything meaningful about changes in climate. Anyone wanting to look at trends in climate and weather, including extreme events, should always look first at data on climate and weather, not economic loss data.

There is another big problem with the dataset. In 2016, NOAA assumed responsibility for assigning loss estimates to the various events that they were counting. What could go wrong?

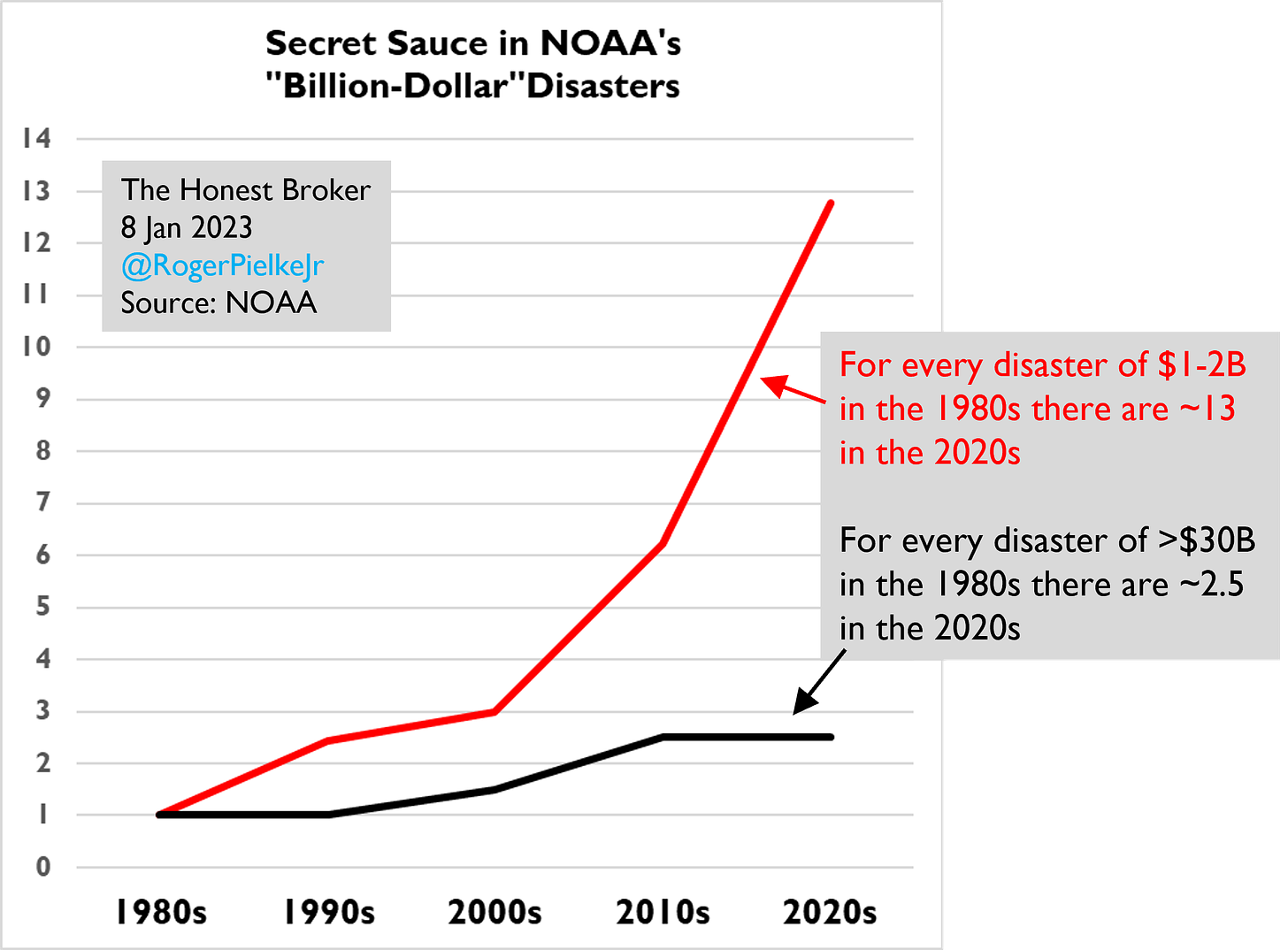

As you see in the graph below, NOAA’s dual roles as scorekeeper and score-creator coincided with a dramatic uptick in the frequency of events that just get over the $1 billion threshold.

The figure above shows that for every disaster between $1 and $2 billion in the 1980s there are 13 of them in the 2020s, an increase ~4x greater than U.S. GDP growth. Meantime, the count of disasters of >$30B in losses has increased over that same period by about exactly the same amount as has GDP.

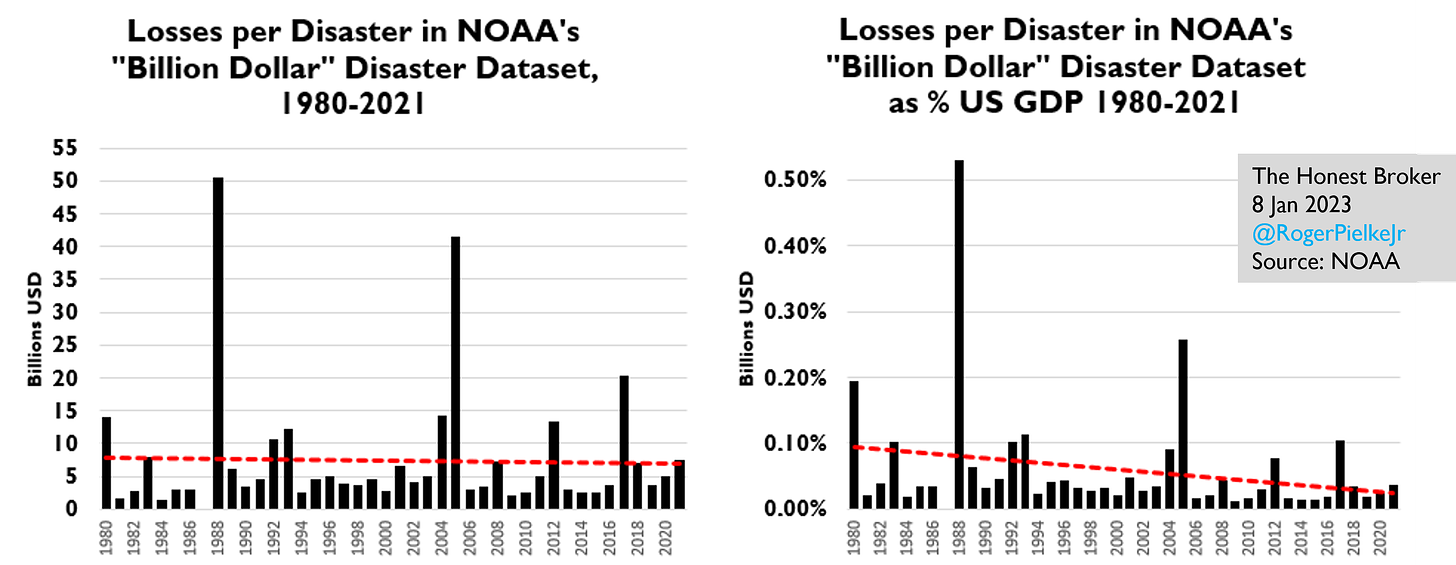

In fact, if we take a look at the annual losses per disaster in the NOAA time series, shown in the left panel below, we see that disasters have not on average increased in intensity since 1980. This is remarkable — and utterly unbelievable — in the content of a U.S. GDP that has increased by almost 3x since 1980.

The panel to the right in the figure above shows the average cost per disaster as a proportion of US GDP. Once again, remarkably and unbelievably, average GDP-adjusted losses in the NOAA dataset have decreased by 80-90% since 1980. Climate change must work in mysterious ways.

Of course, none of this is real.

What it does suggest is that NOAA’s damage estimates may be, how do I put this, somewhat aggressive when it comes to getting events over that $1 billion threshold. We shouldn’t be too hard on NOAA however, as it is an atmosphere and oceans agency — it is not responsible for economics, insurance or loss estimation.

So if NOAA wants to provide scientifically sound loss data, how might it improve its time series on U.S. disasters? The answer is simple: Do away with the billion-dollar meme and look at the entire record of losses. Even better, address the effects of a growing U.S. economy and the correspondingly greater loss potentials over time by normalizing disaster loss data based on GDP (or other factors).

That is exactly what I did in the graph below, based on data from the U.S. Office of Management and Budget (GDP) and reinsurance loss estimates. The graph shows North American catastrophe losses (which are dominated by the U.S.) from 1980 to 2021.

North American catastrophe losses as a proportion of U.S. GDP clearly show no upwards trend. In fact, the opposite is true — losses have decreased by almost half over the past 4 decades. That is exceedingly good news and it is also consistent with scientific understandings of trends in vulnerability, which are sharply downward around the world.

The story here gets even more remarkable. After issues were raised a decade ago about the scientific problems in the “billion dollar disaster” tabulation, to its credit, NOAA recognized that there were methodological issues in its approach. So NOAA commissioned a study of the dataset and methodology, which was peer-reviewed and published in 2013. That study acknowledged,

“the billion-dollar dataset is only adjusted for the CPI [consumer price index, representing inflation] over time, not currently incorporating any changes in exposure (e.g., as reflected by shifts in wealth or population).”

NOAA admitted that the lack of such adjustments had implications for the apparent increasing trend in the count of billion-dollar disasters:

“The magnitude of such increasing trends is greatly diminished when applied to data normalized for exposure.”

Not surprisingly, due to such methodological concerns, the NOAA study concluded:

“it is difficult to attribute any part of the trends in losses to climate variations or change, especially in the case of billion-dollar disasters.”

Read that again. That conclusion remains solid in 2023. However, it has been completely ignored.

In fact, in the years since NOAA has increasingly promoted the dataset as showing an increase in the counts of billion-dollar disasters attributable to climate change. For example, on its website today NOAA says:

“Climate change is also playing a role in the increasing frequency of some types of extreme weather that lead to billion-dollar disasters.”

Scientific understandings of trends in extreme weather and climate events is far more robust than implied by this very imprecise statement, which lends itself over- if not mis-interpretation.

The billion-dollar disaster time series provides a powerful lesson on how easy it is to promote a simple message that fits a particular political narrative but which is completely misleading. Perhaps more importantly, it provides a window into a comprehensive breakdown in the media and in science.

To use David Sirota’s term — the algorithm — the “billion dollar dollar” disaster meme is now associated with enthusiasm for the cause of climate action. That means if a reporter or scientist speaks out to correct the science they risk being viewed as hurting the cause or giving fodder to the bad guys. So apparently, not only must we let the bad science sit unchallenged, but we probably should get on board and promote it. Welcome to climate science in 2023!

Let me close by emphasizing that NOAA is an important agency – I very much enjoyed working closely with many excellent scientists and administrators in NOAA for the 16 years I was part of a university-NOAA cooperative institute. Among NOAA’s many functions are to provide weather data and forecasts that help keep all Americans safe, and the agency does that job exceedingly well. NOAA is too important an institution to get caught up in dodgy science related to climate change, much less the gaslighting common to today’s politics.

The “billion dollar disaster” database is a national embarrassment. NOAA should fix it or end it.

Thanks for reading! Please share this post. I welcome your comments and subscriptions at any level.

I thought it would take a generation for intentionally misleading information to become mainstream in our government, academic and scientific institutions, but I was optimistic.

You are fighting the good fight, but I'm afraid Orwell is winning...no one in on the climate change side of the discussion is embarrassed.

This article reminded me of some of my experience as an actuary for the reinsurance industry.

To somewhat oversimplify, a typical reinsurance contract might promise to reimburse the insurer for a layer of coverage. The layer might go from 1 to 25 million, which means if an individual claim exceeds $1 million, the reinsurer will pick up the excess amount up to 25 million which means they would pay out a maximum of 24 million.

Start with an assumption about the relative distribution of sizes of claims and it's easy enough to calculate the expected amount of coverage in the layer.

Now take that distribution and apply a uniform inflation factor to all claims. What surprised some seasoned insurance executives was the fact that inflation generated a frequency (count of claim) impact more than a severity (size of claim) impact. In an inflationary scenario, the count of claims would increase (by a factor larger than the inflation impact) but the severity would grow at a smaller amount, possibly even not at all. This seems counterintuitive but can be demonstrated for reasonable types of claim size distributions.

This is part of the story of the increase in billion-dollar claims, although as I'm sure you are aware, there's another important factor when it comes to hurricane losses — the increased number of homes built in hurricane prone areas.

What this means is that we expect an increase in billion-dollar claims for two reasons, neither of which are increases in the strength or number of storms.