Are we focusing too little on a climate apocalypse?

Research and assessment emphasize extreme climate scenarios. Some want an even greater focus.

Yesterday, Matt Burgess, Justin Ritchie and I had a new letter appear in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS). The letter was a response to a recent opinion piece in PNAS by Luke Kemp and colleagues (hereafter KXDL22) who argue that “worldwide societal collapse or even eventual human extinction” due to human-caused climate change is currently “a dangerously underexplored topic.”

Apocalyptic visions of climate change are all the rage. For instance, they are a staple of speeches by UN General Secretary António Guterres by who argues that we are presently “firmly on track to an unlivable world.” President Joe Biden often invokes similar rhetoric: “Climate change is literally an existential threat to our nation and to the world.” Just yesterday PNAS published another commentary repeating the arguments of Kemp and colleagues, and again making the case for greater attention to climate change and “civilizational collapse.”

In this post I provide an overview of our exchange with KXDL22, and go into greater detail than we were able to in that short piece. Of course, the views expressed here are mine, not necessarily those of my co-authors.

In their original PNAS opinion calling for more attention to catastrophic climate scenarios — titled “Climate Endgame” — KXDL22 make three empirical claims. The first is that the scientific community is neglecting to pay sufficient attention to extreme climate scenarios. The second claim is that the world is presently on track for as much as 3.9 degrees Celsius temperature increase by 2100, which would be catastrophic. And the third claim is the scientific community should emphasize catastrophic scenarios as a way to motivate desired political action.

Let’s take each in turn.

Does climate science focus enough attention on extreme scenarios?

In our letter, we agree with KXDL22 that the most extreme scenarios presently available in climate research focus on high levels of radiative forcing (specifically 7.0 and 8.5 watts per meter squared). I and my colleagues have published considerable research in recent years on the prevalence of various climate scenarios in the scientific literature and the assessments of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). KXDL22 were apparently unaware of this research.

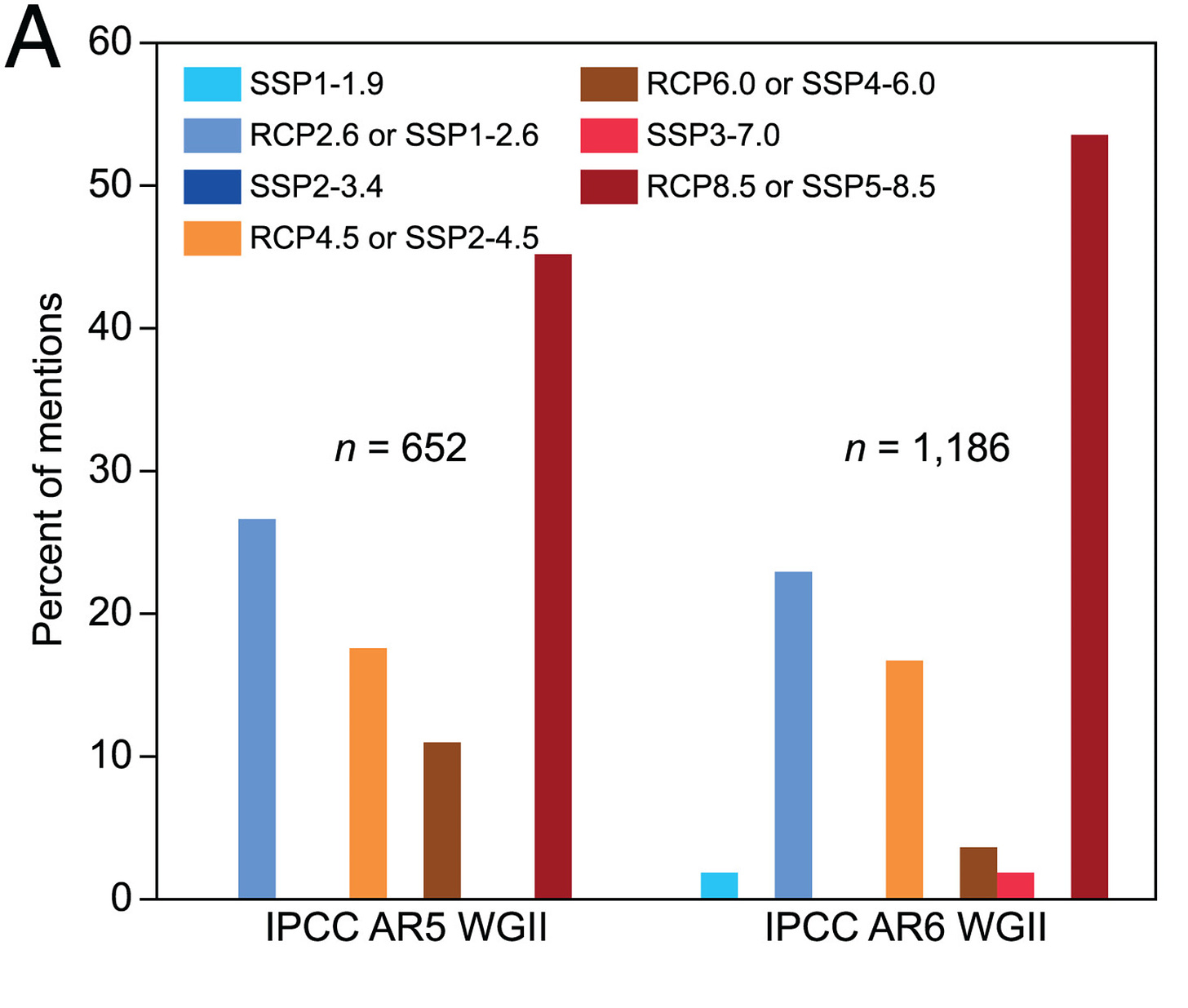

The figure below from our letter in response (hereafter BPR22) shows the frequency of mentions of different scenarios in the IPCC Working Group II reports (on impacts, adaptation and vulnerability) of the most recent two assessments. This is the IPCC working group that focuses on the consequences of projected climate change.

There can be no doubt that the scenarios that receive the most attention, by far, are the most extreme — RCP8.5 and SSP5-8.5. In fact, a more comprehensive accounting that we published last year showed that the most extreme scenario dominated the IPCC AR5 and the U.S. National Climate Assessment, as you can see in the table below.

A simple search of Google Scholar for publications in 2022 that use the most extreme climate scenarios indicates that 20 studies per day have been published this year which use RCP8.5 and SSP5-8.5. The extreme scenarios are by far the most used in climate research, for reasons we explain in depth (start here).

Catastrophic climate scenarios are not being neglected. Far from it. We love them.

Is the current trajectory of projected climate change catastrophic?

A second claim by KXDL22 is that “the current [greenhouse gas emissions] trajectory puts the world on track for a temperature rise between 2.1 °C and 3.9 °C by 2100.” But this claim is based on a paper that uses emissions data only through 2015. More recent analyses, such as that of the Climate Action Tracker (cited by KXDL22), suggest the current trajectory is actually a full degree lower than that claimed by KXDL22, at 2.9°C by 2100, as you see in the figure below.

Only KXDL22 know why they chose to cite an analysis based on 2015 data that gives an upper-end estimate of 3.9 °C rather than an upper-end estimate of 2.9 °C using 2021 data. One clue might be found in their statement that, “we have set global warming of 3 °C or more by the end of the century as a marker for extreme climate change.”

More generally, a large and growing body of research suggests that on current policies, the world is on track for between 2 and 3 degrees Celsius temperature increase by 2100 (e.g., see our recent paper). That is not achievement of the Paris Agreement targets, but nor is it the apocalypse.

Of course, as KXDL22 correctly observe, time does not stop in 2100. To keep global temperatures from continuing to increase will require achieving net zero emissions, a goal that I support and view to be achievable this century.

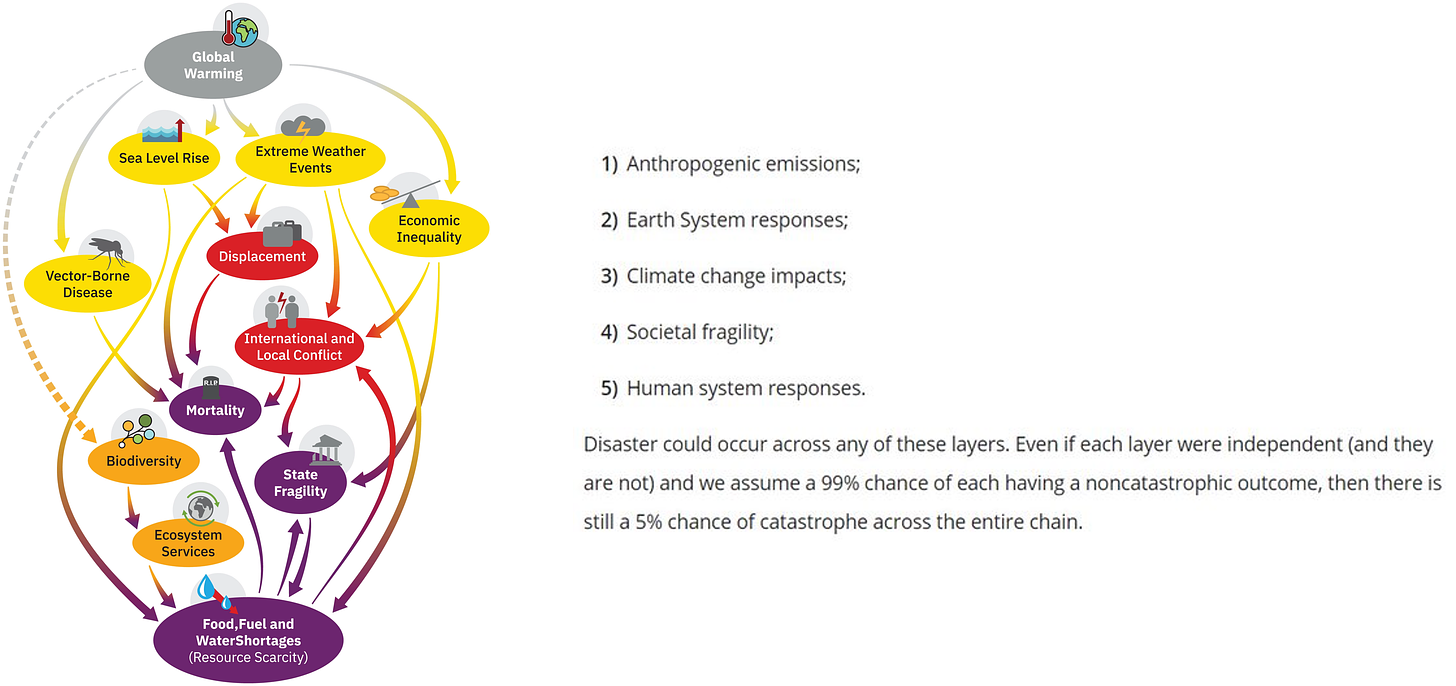

In their response to our letter, KXDL22 make a simple math mistake, which increases their estimate of the likelihood of catastrophic outcomes by a factor of 500 million. The figure below shows an image of “cascading risks” from their original paper, accompanied by text from their response to our letter on the right. They use this framework in stylized fashion to illustrate how “cascading risks” could lead to a 5% chance of a catastrophic outcome. But there is a simple math error here.

KXDL22 assume that risks are additive across their “cascade” (1% + 1% + 1% + 1% + 1% = 5%). However, the appropriate way to assess these cascading risks is to multiply them (i.e., 0.01 to the 5th). So instead of a 1 in 20 risk of a catastrophic outcome, their example indicates a 1 in 10,000,000,000 chance of a catastrophic outcome. Not zero, of course, but pretty small.

Almost 20 years ago I participated in a National Academy of Sciences committee that evaluated research and policy priorities related to abrupt climate change — a somewhat different focus than societal collapse. At the time we recommended:

Any future abrupt climate change might have large and unanticipated impacts. Improved understanding of the processes may increase the lead time for mitigation and adaptation. More-precise estimates of impacts of abrupt climate change could make response strategies more effective. The persistence of some uncertainty regarding future abrupt climate changes argues in favor of actions to improve resiliency and adaptability in economies and ecosystems. Much fruitful work remains to be done to improve our understanding of the history, mechanisms, policy, and social implications of abrupt climate change.

This focus still makes sense.

Can greater attention to catastrophic futures compel political action?

A final claim made by KXDL22 is that we should increase emphasis on catastrophic scenarios because they will be useful in compelling certain political outcomes. They argue, “Knowing the worst cases can compel action, as the idea of “nuclear winter” in 1983 galvanized public concern and nuclear disarmament efforts” and restated this in their response to our letter, “modeling of nuclear winter empowered bottom-up and multilateral disarmament efforts.”

It is always seductive to think that scientists raising an alarm and broadcasting to the public will compel politicians to act in some manner that the scientists wish them to act. In the most extreme versions of this fantasy, the resulting collective action saves the world — see the image in the header of this post! While this story makes for an exciting action film, it is not exactly how things work in the real world.

Lawrence Badash, a historian of physics and nuclear weapons, wrote in 2001 of the impact of the nuclear winter hypothesis on nuclear politics:

“Naïve logic would have the [U.S.] executive branch accept the scientific advice and alter strategic policy accordingly, by marked reductions in the nuclear arsenal. But the politics that brought the administration to office required a diametrically opposite path, one of increasing offensive and defensive capabilities. It was the genius of the Reagan White House to co-opt nuclear winter and claim it was preventing this disaster by continuing its arms buildup. Scientists thereby failed in their goal of political action.”

As readers here will know well, I am not a fan of seeking to use research instrumentally to try to move politics — this is far more likely to bring pathological politics into science, than it is to bring robust science into politics. Using research instrumentally is a recipe for turning science into marketing and may even lead to issues with research integrity.

Let me end on a point of agreement with KXDL22. We certainly need to improve the use of climate scenarios in research and policy. There is a place for emphasizing plausible scenarios, including those that are extreme. There is also a place for exploratory research on currently implausible scenarios that may yet be possible. The future is an unknown and scary place, but I am optimistic that we have all the tools we need to make our way there and thrive while doing it.

Looks like Kemp et. al. replied to your letter. They completely ignore the math mistake, which is introductory probability and statistics 101.

Good post. Your letter was well thought out, concise and tactful.

The original paper "Climate Endgame" was clearly an attempt to debunk your work and the work of others on focusing on reasonable scenarios before it gets traction. Frankly it's their job and in their best interests to promote alarmism and extensive, never ending work on highly unlikely scenarios.

I don't know any of the authors or their qualifications but a quick check shows that they work primarily at places like: "The Center for the Study of Existential Risk" (Oxford), "Centre for Environment, Energy and Natural Resource Governance" (Cambridge), "Center for Health and the Global Environment" (U of Washington), "Future of Humanity Institute" (Oxford), "Fenner School of Environment and Society", The Australian National University. The more fear and anxiety about doomsday they can create makes it easier for them to angle for increased "research" funding and ongoing employment.