A Challenge to Climate Hawks

Please explain how the Inflation Reduction Act actually reduces emissions

If I am a Senator in the U.S. Congress, I am a ‘Yes” vote on the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) of 2022. That is because I judge the merits of the overall bill to be net positive, not because I see it as perfect or do not disagree with parts of it. Significantly, the bill also represents a major legislative approach to policy of the sort which is needed to address major policy issues. Executive action doesn’t do much and it certainly doesn’t foster a durable democratic consensus.

My view is that anyone who doesn’t like the IRA bill should propose amendments to make it better. One of the worst pathologies of our partisan times is the tyranny of “NO!” — no compromise means no policy, and major problems then go unaddressed or get worse. I’d much prefer to see a bill written such that it could gather bipartisan support, but that does not appear to be in the cards for the IRA.

Compromise is essential to democratic governance. As the late philosopher Richard Rorty wrote in 1998, “In democratic countries you get things done by compromising your principles in order to form alliances with groups about whom you have grave doubts.” It is not necessary that everyone agree on everything for progress to occur. To paraphrase Walter Lippmann from more than a century ago, Politics is not about getting everyone to think alike, but getting people who think differently to act alike.

To that end, with this post I want to raise a fundamental question of the IRA and that is how exactly it works to achieve the emissions reductions that its proponents advertise.

I’m putting forward a straightforward challenge to climate hawks who argue that the IRA will dramatically accelerate overall U.S. emissions reductions by 2030. A co-author of the IRA, Senator Chuck Schumer (D-NY), asserts that the legislation will lead to a 40% reduction in emissions from 2005 levels over the next 7 years, compared to a 24% reduction without the legislation. As they say — Big, if true.

Here is the challenge to climate hawks:

With respect to carbon dioxide emissions — the single largest contributor to greenhouse gas forcing and the central focus of proposals to achieve net-zero emissions by 2050 — I simply do not see how the IRA actually reduces emissions. I invite climate hawks to present the case in terms of specific policy mechanics and resulting causality for how the legislation will reduce carbon dioxide emissions. Because I’m not seeing it. I will be happy to publish the best responses here in a subsequent post.

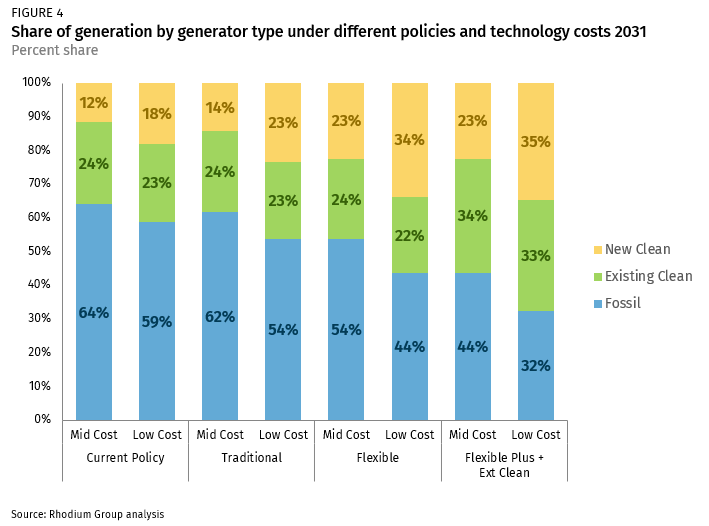

Several consulting groups have asserted that they have modeled the provisions of the IRA to estimate the effects of the bill on emissions in 2030 (unfortunately, these seem all to be black-box models). For instance, The Rhodium Group asserts that tax credits of the sort that are central to the IRA for new and existing carbon-free power can cut electricity generation from fossil fuels by as much as half this decade:

Under current policy, fossil fuels provide 58-64% of total generation in 2031. Long-term, full-value, flexible tax credits with direct pay cut that range to 44-54%. When existing clean resources are retained, the range drops to 32-44% of total generation (Figure 4)

How realistic are such claims? Let’s look at some numbers.

In 2021, according to the Energy Information Agency, fossil fuels provided 60.8% of U.S. electricity generation. Nuclear was 18.9% and renewables (hydro, wind, solar etc.) came in at 20.1%. To get to a 32% to 44% reduction in generation of electricity from fossil fuels would require electricity generation from fossil fuels be reduced by 700 to 1,200 to billion kilowatt-hours (kWh) from 2021 levels. In comparison, in 2021 wind generated a total of 380 billion kWh and solar 115 kWh.

What do these numbers mean?

To simply replace the needed reduction in fossil fuel generation with renewables would require wind and solar generation increase by anywhere from 1.4x to 2.4x from current levels over the next ~7 years. In 2021, wind and solar capacity was just over 200 gigawatts (GW). If we hold the ratio of capacity to generation constant, that means that an additional 280-480 GW of renewable capacity would have to be deployed by 2030 — a rate of ~40-70 GW per year. The record rate of deployment was 30 GW in 2020, so a doubling might be doable.

However — my analysis so far has one huge problem — it assumes that wind and solar electricity generation are equivalent to fossil fuel generation. They are not. Wind and solar are highly variable sources of electricity (because sometimes the wind doesn’t blow and every evening it gets dark), whereas fossil fuels are not. Variable renewables require back-up, so they cannot be deployed interchangeably for fossil fuel generation.

In fact, according to the American Public Power Association, as of February, 2022 there were about 52 gigawatts of new natural gas power capacity under construction, permitted, pending application or planned. Presumably some part of this new capacity is to replace retiring coal plants and some is to back up rapidly deploying renewables. The new natural gas capacity is on top of about 548 GW of capacity already in service (note: through 2026 about 21 GW of natural gas capacity are planned to be retired). If you are still with me, that means that electricity produced by natural gas is expected to grow over most of the current decade.

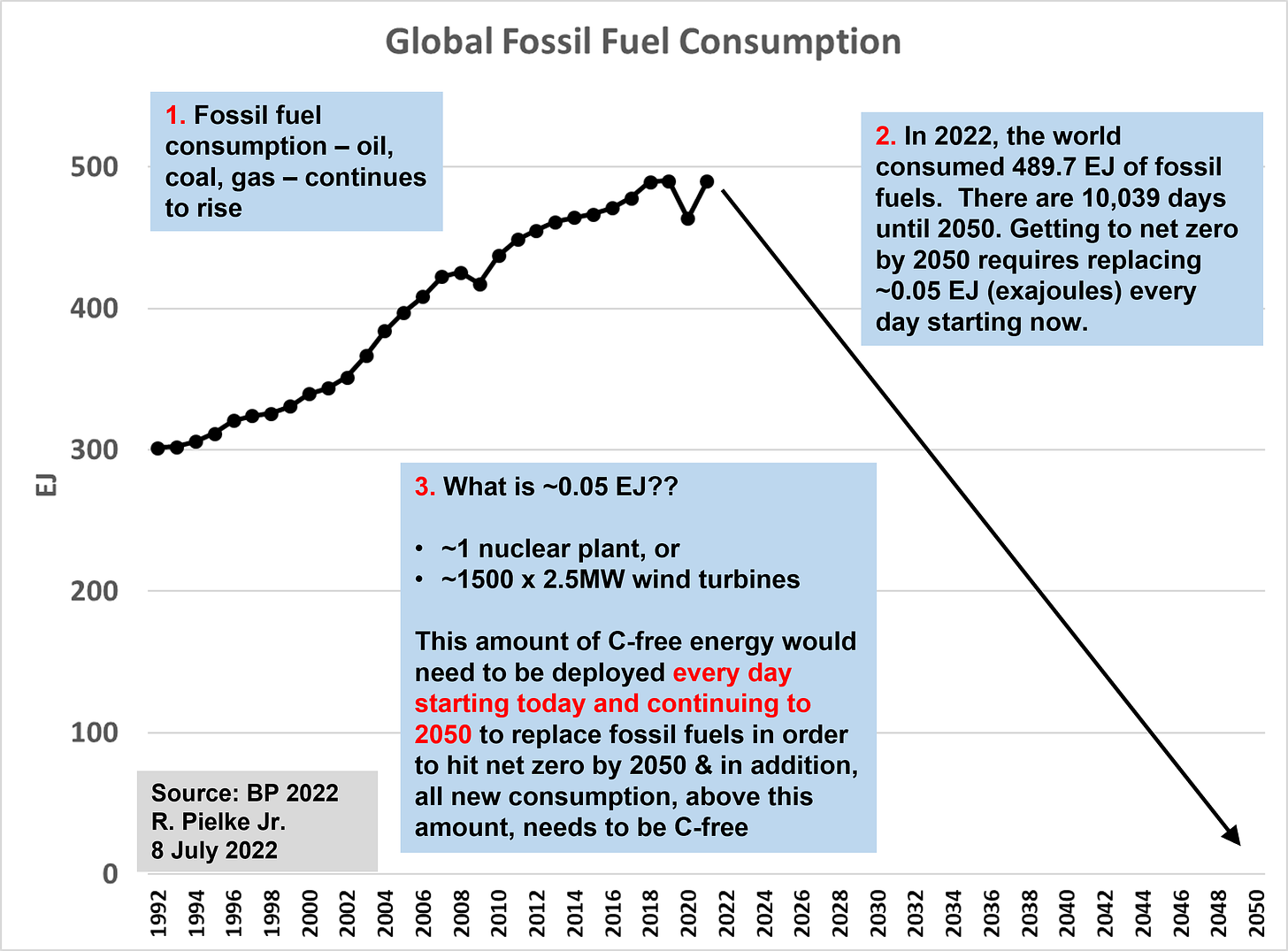

A search of the 725-page IRA bill finds “natural gas” mentioned on just 11 pages, and absolutely no mention of accelerated retirements (or actually, any retirements) of natural gas power plants. It is important to underscore the obvious but often overlooked point that the deployment of carbon-free energy does not by itself do anything to accelerate decarbonization of the economy. Only the retirement of carbon-intensive sources of energy can do that — which means less burning of oil, coal and natural gas, as shown below.

It is of course conceivable that the emissions reductions resulting from the IRA that are foreseen in black-box models arise from the replacement of carbon-intensive coal with less-carbon-intensive natural gas. If so, that may help the U.S. come closer to a 2030 target, but more fossil fuel power plants (from any source) would also move the U.S. further away from its 2050 net-zero target. After all, achieving net zero means that all fossil fuel electricity will either need to be retired or retrofit with technologies of carbon capture and storage that presently do not exist at scale.

Perhaps the proposed emissions reductions of the IRA come from assumptions of decreased electricity demand or from greenhouse gases other than carbon dioxide (like methane). Maybe the assumption is that aggressive financial incentives for more rapid deployment of renewables somehow inevitably leads to the early retirement of fossil fuel power plants. If any of these mechanisms are carrying the weight of projected future emissions reductions, then we are well down the path of kicking the can down the road, because they would skirt the primary challenge here, which is dramatically reducing reliance on fossil fuels.

OK climate hawks, over to you. I challenge you to explain the policy mechanics of how emissions reductions actually occur under the IRA. I am particularly curious about how much natural gas electricity generation is projected to be in place in 2030, and if less than today, how that actually occurs.

I hope to learn something from this challenge, and hope you will also. I’ll be happy to publish the best responses in a future post. Thanks all!

Paying subscribers to The Honest Broker receive subscriber-only posts, regular pointers to recommended readings, occasional direct emails with PDFs of my books and paywalled writings and the opportunity to participate in conversations on the site. I am also looking for additional ways to add value to those who see fit to support my work.

There are three subscription models:

1. The annual subscription: $80 annually

2. The standard monthly subscription: $8 monthly - which gives you a bit more flexibility.

3. Founders club: $500 annually, or another amount at your discretion - for those who have the ability or interest to support my work at a higher level.

Don’t we also have to replace at least a substantial fraction of nuclear too? For example, here in New York Indian Point 3 is slated to close in the next few years.

My understanding is that regulatory reform is part of a “side-deal”? Seven years is not very long when it comes to permitting on federal land. Would be interesting to see what mechanics/assumptions are behind the substantial RE build-out in real-world terms (where, how and when).

PS when politicians make claims, they are usually based on a potent mix of wishful thinking and hot air.